CMP Review 2024-02-08

February 8, 2024

In contemporary nature study methods, the naturalist is inseparable from his notebook. John Muir Laws goes so far as to prefer an over-the-shoulder bag to a backpack so that the notebook may be more easily retrieved while in the field. But is this what Charlotte Mason had in mind when her 1886 Home Education lecture referenced a “diary” in which a child could make entries about what he observed in nature?

In 1893, Charlotte Mason asked M. L. Hodgson to improve the practice of nature study at the House of Education. Her task was “to make the students as keen observers, as true lovers of, and as conversant with Nature as she herself is.” Miss Hodgson settled on a plan to require “each student keep an illustrated note-book, modelled somewhat on the lines of note-books which she had herself been in the habit of keeping for her own purposes.” This was no mere diary. This was a notebook of prose and art.

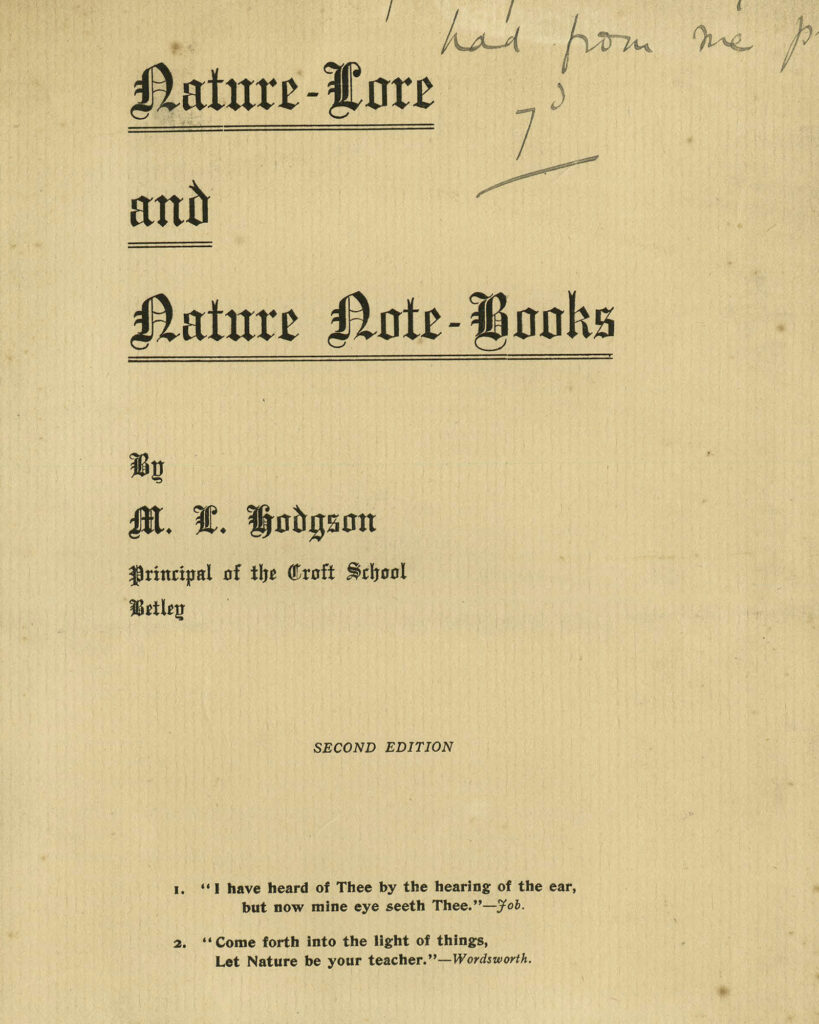

We find that Hodgson’s influence was not to be limited to the House of Education. By 1900 a pamphlet by Miss Hodgson, “Lecturer at the ‘House of Education,’” was being offered to PNEU branches and members. Entitled Nature-Lore and Nature Note Books, it described the practice of nature study in the words of the woman who refined the practice at the House of Education.

When I reviewed Hodgson’s pamphlet I was intrigued by one tip among many: “A small pocket note-book may be taken out by the children in which to jot down what they want to remember, and for the rough lists of flowers, birds, insects, etc., which might be forgotten if there was not time to write the account of the walk directly they came home.”

Of course it’s good to remember what we see. And writing a journal entry at home can be a lovely way to reflect and meditate on a nature walk. But even Hodgson approved of taking some notes in the field. And a century before Laws she anticipated some of his methods: make sure that little note-book is as easy as possible to retrieve on the go.

@artmiddlekauff