The Living Principles of Sloyd

Reading through Charlotte Mason’s six volumes, you will rarely come across the word “sloyd,” but if you look through the archives you will find statements like this: “Miss Mason always says she believes Sloyd to be the most valuable and most educative of all the handicrafts” (Pennethorne, 1906, p. 3). So what exactly is sloyd and why did Mason consider it to be so important? Here begins a series of articles explaining what sloyd is, why it was important to Mason, how it was used by the P.N.E.U., and how you can incorporate it into your teaching.

Reading through Charlotte Mason’s six volumes, you will rarely come across the word “sloyd,” but if you look through the archives you will find statements like this: “Miss Mason always says she believes Sloyd to be the most valuable and most educative of all the handicrafts” (Pennethorne, 1906, p. 3). So what exactly is sloyd and why did Mason consider it to be so important? Here begins a series of articles explaining what sloyd is, why it was important to Mason, how it was used by the P.N.E.U., and how you can incorporate it into your teaching.

What is Sloyd?

In the simplest terms, “sloyd” comes from the Swedish word meaning “handicraft.” Woodworking was the most popular implementation of sloyd, but it also included knitting, sewing, metal, paper, and cardboard. Mason favored paper and cardboard. Sloyd was uniquely systemized for the classroom. The purpose was not vocational training, but rather education of the person. In the 1870’s Otto Salomon opened a sloyd woodworking school, which became a teacher training school and allowed the philosophy of sloyd to travel across the world. On April 27, 1893 Mr. C. Russell gave a lecture describing the philosophy of sloyd to the members of the Woodward branch of the P.N.E.U. (P.N.E.U, 1894, p. 319).

Principles

Sloyd, like Charlotte Mason’s method, can best be understood by a discussion of the principles that guide the system. In his lecture, Mr. Russell says:

These fundamental principles may be summed up thus:—

(1) The aim must be educational, not technical.

(2) The teacher must be an educator, not a mechanic.

(3) The teaching must be, as far as possible, individual.

(4) The work must be systematic and progressive, and follow a sound method. (Russell, 1894, p. 322)

We will look at each of these principles individually, and I hope you will be able to see how they dovetail with Miss Mason’s own philosophy.

1. “The aim must be educational, not technical.”

Mr. Russell tells us explicitly:

The teacher of Slöjd that is, like the teacher of everything else, must ever bear in mind that his business is to make a good and wise man of the child, not a clever carpenter. (Russell, 1894, p. 322)

Miss Pennethorne, former student of the House of Education, says something very similar:

The child is only truly educated who can use his hands as truly as his head, for to neglect one part of our being injures the whole, and the learned book-worm who is ignorant of the uses of a screw-driver, also lacks that readiness and resourcefulness, mental neatness and capability, and reverence for labour and its results, which a knowledge of practical matters gives. (Pennethorne, 1899, p. 561)

Sloyd lessons, like all of their other lessons, are meant to develop the whole person of the child: not only to enhance his manual dexterity and physical health, but also to give him the ability to be a useful part of the community and to connect with people from all walks of life. It teaches him to respect the working man or woman and not fall under the dualistic belief that some kinds of work are more important than others, because the importance of educational sloyd is not attached to the work, but to the worker (Salomon, 1892, p. 1).

We also do not teach sloyd with a view towards the monetary value of the training. In other words, we don’t teach sloyd to prepare a child for his future job, like vocational training would do, and we don’t teach any handicraft so that the child can profit from the things he can make now. Mr. Russell is quite clear:

… there must be no more question of the money value of completed work than of that of completed copy-books—nor must a boy be encouraged to persevere, because skill in handling tools may be useful to him in after life—though useful it undoubtedly will be—but because clumsy and ignorant hands disgrace a man no less than a clumsy and ignorant head. (Russell, 1894, p. 322)

The comparison Russell makes between copy books and handwork is telling. Can you imagine selling a book of copywork or commonplace book? Or encouraging a child to do them because of financial gain?

Mrs. Steinthal, Mason’s good friend and P.N.E.U. co-founder, agreed. In a Parents’ Review article she says, “The work of the children has no commercial value and we do not teach it with this object” (Steinthal, 1897, p. 415). The article ends with a short conversation in which the Chairman states his own misconception, admitting that they had been teaching the children with that idea in mind. Mrs. Steinthal confirms that making money should have no part in training children in handicrafts—not only sloyd, but all handicrafts. In our current Etsy culture, it is too easy to encourage work to be done so that children can profit by their efforts. Don’t get me wrong; I am an Etsy fan, but when it comes to the children, if the goal becomes profit, handwork will lose its real value, which is training hearts and minds, not hands only.

Mrs. Steinthal, Mason’s good friend and P.N.E.U. co-founder, agreed. In a Parents’ Review article she says, “The work of the children has no commercial value and we do not teach it with this object” (Steinthal, 1897, p. 415). The article ends with a short conversation in which the Chairman states his own misconception, admitting that they had been teaching the children with that idea in mind. Mrs. Steinthal confirms that making money should have no part in training children in handicrafts—not only sloyd, but all handicrafts. In our current Etsy culture, it is too easy to encourage work to be done so that children can profit by their efforts. Don’t get me wrong; I am an Etsy fan, but when it comes to the children, if the goal becomes profit, handwork will lose its real value, which is training hearts and minds, not hands only.

2. “The teacher must be an educator, not a mechanic.”

This is excellent news for most of us. Oftentimes handicrafts are among the subjects dropped during the school year simply because the parent feels inept or unprepared to teach them. All handicrafts require only that the teacher be a step or two ahead of the student; paper and cardboard sloyd are especially practical in this respect. While many of us would feel intimidated at the thought of learning wood sloyd, paper and cardboard are ideal for beginning teachers. Again from Mrs. Steinthal:

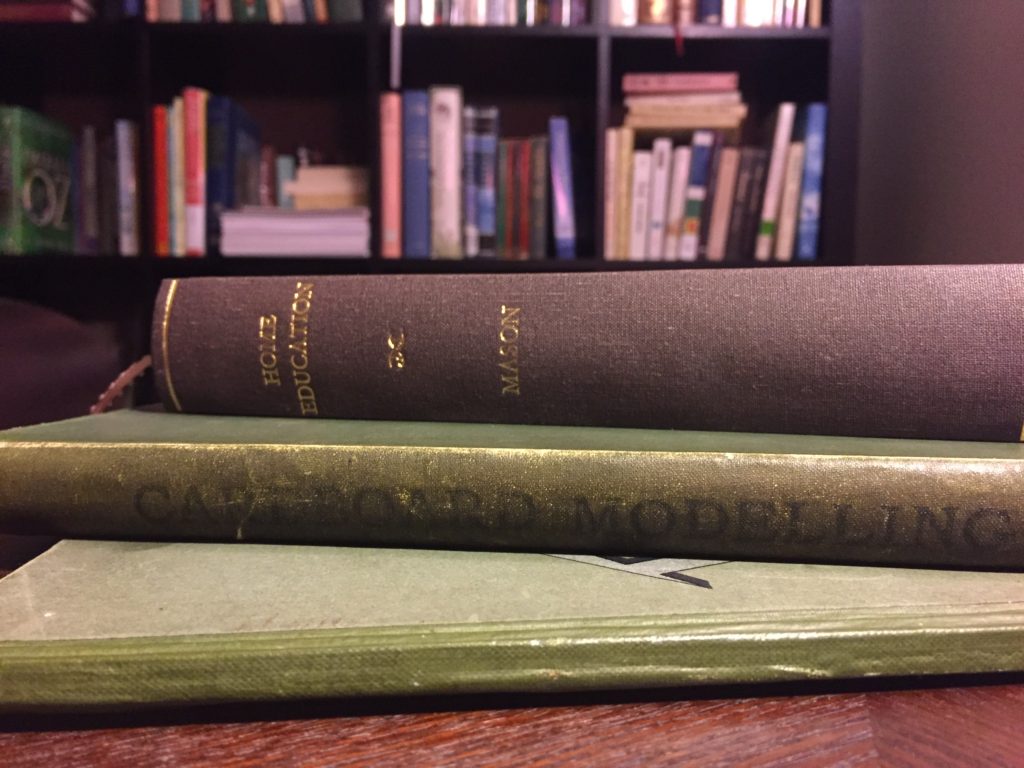

I would press teachers very earnestly to study Mr. Heaton’s book, which is so carefully prepared that any adult could work the models without any previous training, and then teach it to her pupils. (Steinthal, 1894, p. 925)

Having worked through many of the models myself, I can say that, while challenging, they can all be done by the teacher well enough. I believe it is important to do many of the models for oneself in the same way that it is good to practice narration. Some things seem much easier than they actually are:

If you ever want to see how untruthful, lazy, and depraved and fallen human nature is, go yourselves and see how you fare over a first morning at Sloyd—it is a revelation of one’s own inner blackness and want of intellectual truthfulness; to the children, however, who are not yet fully cursed with our self-consciousness, it is a great treat and a great education. (Pennethorne, 1899, p. 561)

So by doing the models, the teacher will be better able to guide the progression of skills built and understand if he is asking too much of the student. Which leads me to the third principle.

3. “The teaching must be, as far as possible, individual.”

While most of us do not teach in a classroom, many of us have more than one student to teach. When teaching sloyd, we must keep in mind that, like reading or math or any other skill-based accomplishment, the progress varies by the individual student and must be adjusted accordingly. In the Parents’ Review article “Manual Training,” Miss McMillan says:

… we ought to observe order in general manual training, as various centres of the nervous system develop in a certain order… Every teacher should observe the order of the child’s exertions, and follow their natural sequence. (McMillan, 1898, p. 430)

Many of us, as homeschooling parents, chose not to put our children in the classroom for this very reason. We realize that a one-size-fits-all curriculum will not suit our child, but still we can fall into the same mindset, thinking that there is a level of mastery expected by a certain age. Miss McMillan is reminding us that we must observe the individual child for his own natural sequence of development and then we adjust.

Even the classroom teacher of sloyd recognizes that we cannot expect children to develop or progress at the same level. I think Mr. Russell explains the idea perfectly with this analogy:

It would be just as absurd to put tools and materials into the hands of a class and expect them to perform each successive step of a given operation at one and the same time, as to set their dinners before them and ask them to carry out the different steps of that complicated operation simultaneously and satisfactorily. (Russell, 1894, p. 324)

The focus of lessons is not on the teacher giving instruction, but on the student learning, interpreting, and imagining, as he works through his model at his own pace and according to his own ability. We must understand that children will progress at different rates and in different ways. So we only give him work that we know he is capable of executing perfectly. In Home Education, Miss Mason says:

The focus of lessons is not on the teacher giving instruction, but on the student learning, interpreting, and imagining, as he works through his model at his own pace and according to his own ability. We must understand that children will progress at different rates and in different ways. So we only give him work that we know he is capable of executing perfectly. In Home Education, Miss Mason says:

No work should be given to a child that he cannot execute perfectly, and then perfection should be required of him as a matter of course. (Mason, 1989a, p. 160)

Then later she says:

… [children] should be taught slowly and carefully what they are to do; … that slipshod work should not be allowed; … and that, therefore, the children’s work should be kept well within their compass. (Mason, 1989a, pp. 315-316)

When I first read this, the idea seemed impossible to me. I couldn’t understand how perfect work could be expected from a child who is just learning. As I have come to understand Mason better and thought about this in light of my own manual training, the idea makes sense and is not as rigid as I first imagined. Perfect work is not expected, but perfect execution.

The word “execute” means “to carry out fully: put completely into effect… to do what is provided or required by” (Merriam-Webster, 2003). It is possible to go through the steps with perfect execution and still do an imperfect job. If you have ever followed a recipe and the dish turned out just a little off, you know what I mean. While our end results are often imperfect, it is perfection we are striving for. Be ye therefore perfect (Matthew 5:48, KJV). We know that we are not perfect, but we strive for it nonetheless.

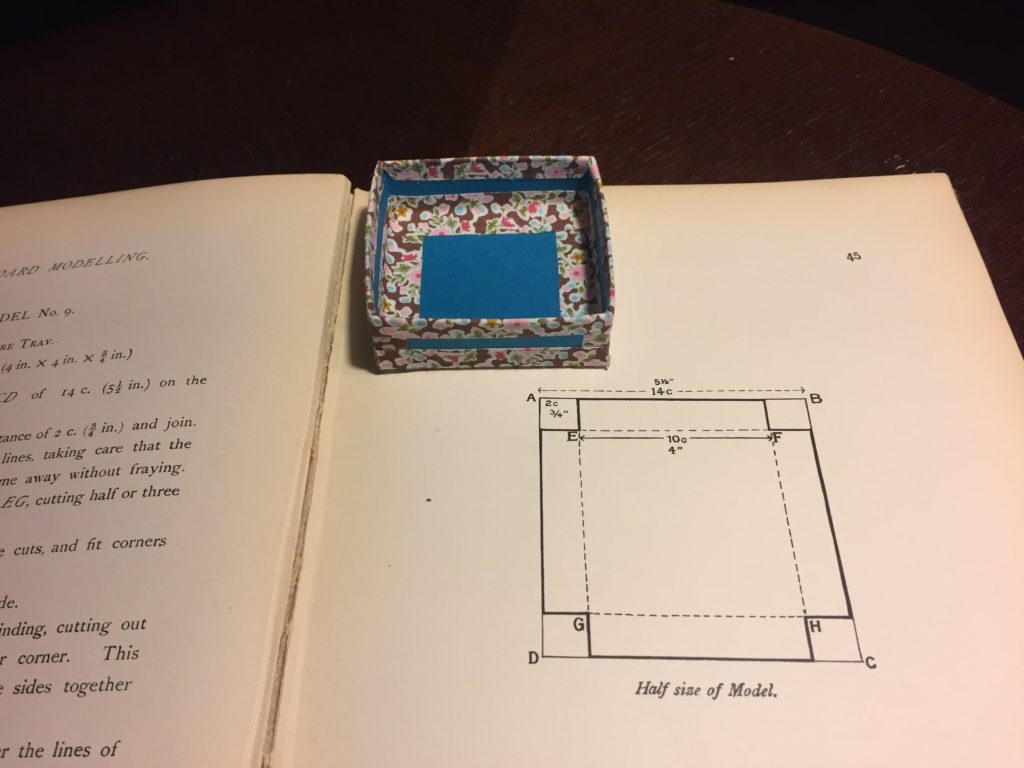

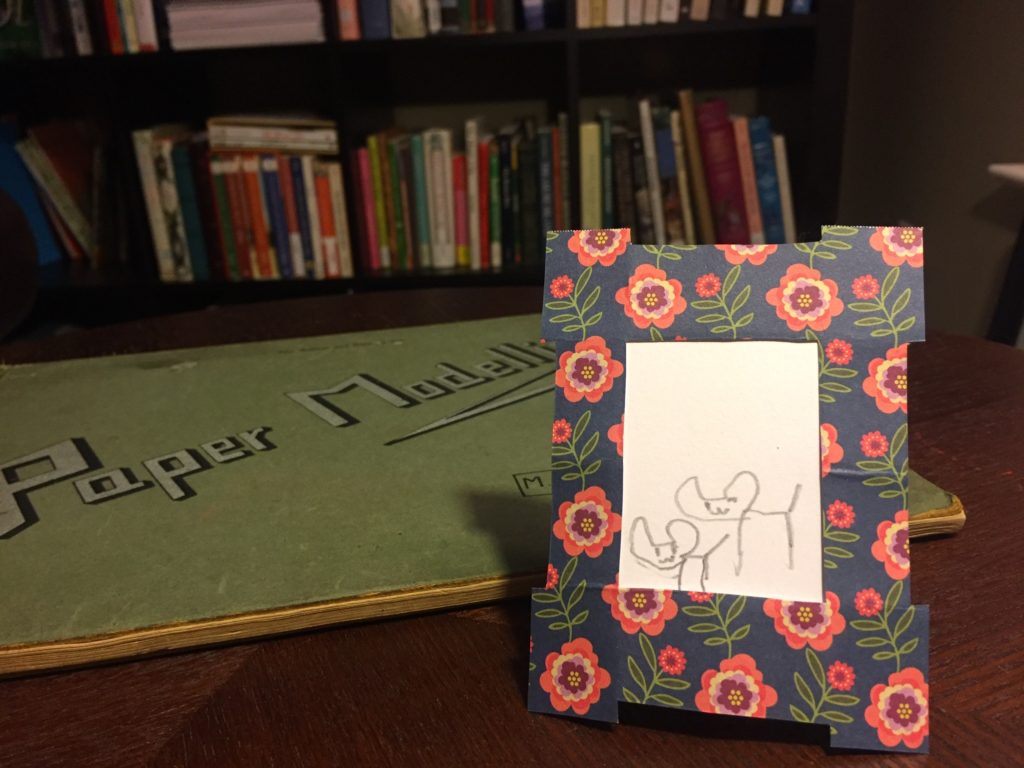

Now in sloyd, and in all things, we must balance this idea with the personhood of the child. “OFFEND not” (Mason, 1989a, p. 12). William Heaton, author of the book, Cardboard Modelling, the book used by the PNEU throughout the programs available to us, says:

Rigid accuracy either in cutting or binding, should not, in the working of the earlier models, be insisted upon. If the teacher is satisfied that the work has been done to the best of the pupil’s ability, it would be unwise to insist upon too many repetitions of the exercise. (Heaton, 1894, p. 4)

By focusing on the development of good habits of perfect execution, the work will improve as skill grows. Which brings us to the fourth principle laid out by Mr. Russell.

4. “The work must be systematic and progressive, and follow a sound method.”

I believe that this idea is not only one that accurately describes sloyd, but all handicrafts that could have a place in a Charlotte Mason education. Continuing the quote above, Russell tells us:

In other words, it must be true to certain fundamental and universally accepted educational principles, and proceed step by step, from the easy to the difficult, from the known to the unknown, and so on. School work-shops do exist, I believe, conducted upon the opposite system, where, from a foolish belief that interest can only be sustained by giving more or less freedom of choice and action, boys (and perhaps girls) are allowed to attempt whatever their fancy suggests to them, however lofty their flights, and however inexperienced their fingers. But is this sacrifice of method essential to the awakening and sustaining of interest in the class-room? And if not in the class-room, why in the work-shop? Nay, is not the very opposite the truth—that the easier the stages by which you lead the child along a new road, the more skillfully you, with your hidden art, enable him to vanquish difficulty after difficulty, as of his own accord, the more surely will he gain a sense of real power, and with that sense, a real interest. (Russell, 1894, pp. 324-325)

There are a few ideas I want to bring out within this quote.

First, there must be “certain fundamental and universally accepted educational principles, [that] proceed step by step, from the easy to the difficult, from the known to the unknown…” Simply put, there must be a right way, an accepted way, to do a thing. It is the job of the teacher to know, or at least know where to find, instructions for the accepted method. The child is building skills, and he must have a solid foundation to build upon.

The next idea that I think is especially important to us today is that of “freedom of choice and action.” In my own experience as a student and in the workforce, creativity is highly valued and much emphasis is placed on it, but I believe that there is a disconnect in our modern culture. Creativity is the end result after method is understood and mastered. We know that we cannot expect a child to write well if he has never read good stories, but he may still write. The same is true of handwork. If a student is not shown the way things should be done well, he develops his own methods, methods which create bad habits of body and mind, and their true creativity is stultified.

My former profession is that of hair cutter and colorist in high-end salons. I also served as a teacher to assistants before they were allowed their own clientele. I found that the students who were allowed the most freedom to develop their own method before training with me were those who were the most difficult to teach. Not only did they have bad habits when it came to the physical act of cutting hair, but they were also the most arrogant and least willing to learn. Before I could teach them the methods and standards set by the salon, I had to break them of their bad habits and work to change their mindset to one of docility. This is why it is so important to understand that there must be a set and progressive method followed.

If we understand our role as that of a guide, we can see the truth of Russell’s statement:

… the easier the stages by which you lead the child along a new road, the more skillfully you, with your hidden art, enable him to vanquish difficulty after difficulty, as of his own accord, the more surely will he gain a sense of real power, and with that sense, a real interest.

And as we know, Mason is more concerned with how much the child cares (Mason, 1989c, pp. 170-171).

Mrs. Steinthal (1897, p. 416) gave us some additional ideas that fall under this principle of definite method:

- “The exercises must follow in progressive order.” So no skipping around the book.

- “The exercises should admit of the greatest possible variety,—it takes a careful observer and a true teacher to discover that a model may be at the same time too easy for the mind and too difficult for the hand.” This takes us back to the idea of teaching to the individual and watching for the natural progression of each child. We adjust based on the child, while moving forward step-by-step.

- “The exercises should result in making a useful article, to sustain interest in the work.” As Mason has told us, no futilities (Mason, 1989a, p. 315). We don’t waste the child’s time or our own; we do things worth doing.

Conclusion

Sloyd, like all subjects in a Charlotte Mason education, is not difficult, but it does require an intentional commitment to a philosophy. Sloyd can be simply defined, and models can be made by rigidly following instructions in a book, but in order to truly understand sloyd, and especially to understand the overlap with Mason’s philosophy, we must explore the driving principles behind the ideas. Through this article, I hope you have been able to see the ideas common to both the sloyd philosophy and that of the P.N.E.U. In the next article, we will look at the benefits that can come when these principles are lived out.

Sloyd, like all subjects in a Charlotte Mason education, is not difficult, but it does require an intentional commitment to a philosophy. Sloyd can be simply defined, and models can be made by rigidly following instructions in a book, but in order to truly understand sloyd, and especially to understand the overlap with Mason’s philosophy, we must explore the driving principles behind the ideas. Through this article, I hope you have been able to see the ideas common to both the sloyd philosophy and that of the P.N.E.U. In the next article, we will look at the benefits that can come when these principles are lived out.

References

Heaton, W. (1894). A manual of cardboard modelling. London: O. Newmann & Co.

KJV. (2009). (Electronic Edition of the 1900 Authorized Version). Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc.

Mason, C. (1989a). Home education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Mason, C. (1989c). School education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

McMillan, M. (1898). Manual training. In The Parents’ Review, volume 9 (pp. 429-431). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Pennethorne, R. (1899). P.N.E.U. principles, as illustrated by teaching. In The Parents’ Review, volume 10 (pp. 549-563). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Pennethorne, R. (1906). Cardboard sloyd. In L’Umile Pianta, April, 1906 (pp. 3-6). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

P.N.E.U. (1894). P.N.E.U. notes. In The Parents’ Review, volume 4 (pp. 318-320). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Russell, C. (1894). On some aspects of slöjd. In The Parents’ Review, volume 4 (pp. 321-333). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Salomon, O. (1892). The teacher’s hand-book of slöjd. (M. Walker & W. Nelson, Trans.). Boston: Silver, Burdett & Co.

Steinthal (1894). Aunt Mai’s budget. In The Parents’ Review, volume 4 (pp. 922-931). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Steinthal (1897). The value of art training & manual work. In The Parents’ Review, volume 8 (pp. 414-418). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Merriam-Webster. (2003). Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. (Eleventh ed.). Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Inc.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

One Reply to “The Living Principles of Sloyd”

I think I may have been in a school that still taught sloyd as a child… I recall working in the wood shop building little things in second, third, fourth grade… I think this experience was very useful and met the desire of sloyd to teach the value of the worker!