Building Without Scaffolds

June was a big month for me: it was my first time teaching a workshop about the Charlotte Mason method. I was the local hostess for the Charlotte Mason Soirée Summer Mountain Mini, and my topic was scaffolding. I worked out a session description with my co-presenter:

With such a rich feast it’s easy to think the living books will do it all! But Charlotte laid out guidelines for how to scaffold lessons to get the most from each course. Join these two moms as they go through the how and why of scaffolding lessons.

One of these “two moms” was me, and I was really nervous! I had never done anything like this before, but I really wanted to get it right. I scoured Mason’s volumes and many Parents’ Review articles to prepare for the class. I wanted to have all of my research lined up so I could give accurate information to the teachers taking my class. I had all of my information ready to go, but I was left scratching my head. In all my research, I could never find a place where Charlotte Mason actually used the term scaffolding. I couldn’t find it in The Parents’ Review either. How could I explain Charlotte Mason’s “guidelines for how to scaffold lessons” when she never actually used the term?

My workshop went well, but I decided to keep digging in the weeks and months that followed. During that time I came across a two-part article by Elsie Kitching called “The Meeting” that really got me thinking. In her article, she discusses how teachers are guilty of educational jostling, and she explains how this hinders the students and keeps them from truly being educated. To illustrate her point, she quotes William Blake:

Great things are done when men and mountain meet:

This is not done by jostling in the street.

She says, “Let us away with jostling, said the discoverer, give the child a chance to meet the mountain and you will see he has the power to do so” (Kitching, 1921, p. 92). Like Mason, she understands that children are born persons, and each child has “powers of mind which fit him to deal with all knowledge proper to him” (Mason, 1989f, p. xxx).

To explain what jostling does, Kitching draws from the story “The Sing-Song of Old Man Kangaroo” by Rudyard Kipling (1912, pp. 85-99). When the story begins, Old Man Kangaroo doesn’t look like a kangaroo yet. He begs the gods to change him into a unique animal, one that everyone will love and will chase after. One of the gods agrees and sends Yellow Dog Dingo to chase the Kangaroo endlessly (because that is what a dingo does—chase without question). Kangaroo is chased out of his house, out of his regular meal times, and eventually his shape and appearance are altered. Now he has different legs and a longer tail. This was not what he expected! Yellow Dog Dingo was a “means” to an end and it wasn’t the end Kangaroo envisioned. Kitching writes:

In the educational world, too, there are ‘Yellow Dog Dingos’ who spur their victims on to such efforts that the elysium of true education is lost in the shifting sand-hills of endless discussions as to ways and means. (Kitching, 1921, p. 44)

With all my notes from my first workshop in front of me, I began to ask myself this question: as a teacher, am I putting myself through unnecessary panting, aching legs, and chasing, never getting closer to the end, with all of my unnecessary lesson preparation and worry over whether my students will learn all of the right things? Am I meant to jostle my students, to chase them down to ensure knowledge is being learned? Am I drifting into the area Mason warns us of, where “Children … are in danger of receiving much teaching with little knowledge” (Mason, 1989f, p. xxx)? Is my painstaking attention to lesson-planning leading to an unintended result? Am I wearing myself out unnecessarily in an effort to make sure my student is learning the “correct” things? Am I letting the delight of education slowly slip away?

Then in Kitching’s article I came across the word I had been searching for all these months. Scaffolding. I stopped dead in my tracks. Kitching was not telling me how to scaffold. She was telling me not to scaffold at all:

They are taught ‘composition,’ to put words together, to put sentences together, to compose a miserable paragraph in which half the words are left out, to correct errors which the teacher makes on purpose, to punctuate with painful accuracy dull sentences from which the tired teacher has drained any atom of imagination. Geography it is said must be taught by pictures and models, science by experiments. In fact education becomes the building up of minute and careful scaffolding through which the child may peer at the mountain if he has any curiosity left to do so! (Kitching, 1921, p. 52)

And to set my head spinning, she used the word not once, but twice:

The mind does not build on such a scaffolding as that erected in “On applying the Golden Rules” … It grows and produces fruit like any natural growth when it is fed for emphasis, sequence, turns of phrase, etc., come naturally to a well-fed mind. Children brought up in this way do not find composition any effort for they are given material for it. (Kitching, 1921, p. 93)

As I read Kitching’s article, I loved everything she said about how bad jostling is. Then the realization began to dawn on me. Kitching was actually using my beloved term scaffolding as a synonym for this dreaded thing, jostling.

Suddenly this became real. Why does almost everyone in the Charlotte Mason community use a word to describe a teaching strategy that Mason’s dear follower Elsie Kitching said was a bad thing? I had to do some digging. I followed the trail to a Russian psychologist named Lev Semenovich Vygotsky (1896-1934). It turns out that Vygotsky wrote a lot about education, and he “carried out his highly innovative research during the 1920s and early 1930s, writing prolifically on the relationship of social experiences to children’s learning” (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. vii). In fact he, with his two closest colleagues, “has often been given sole credit for the origin of sociocultural theory” (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. 3).

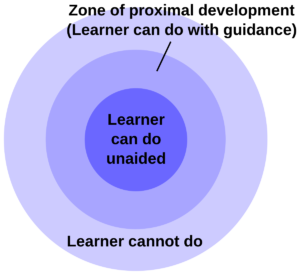

What does this have to do with scaffolding? Well, a key element of his sociocultural theory is the “zone of proximal development (ZPD)”:

What does this have to do with scaffolding? Well, a key element of his sociocultural theory is the “zone of proximal development (ZPD)”:

The zone of proximal development is the hypothetical, dynamic region in which learning and development take place. It is defined by the distance between what a child can accomplish during independent problem solving and what he or she can accomplish with the help of an adult or more competent member of the culture. (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. 5)

The idea is that for a child to learn, he has to get into the zone(the ZPD). And how can he get into that zone? According to Vygotsky, it’s “with the help of an adult.” Can you guess what that help is called?

We have already mentioned the metaphor that has emerged in the literature to describe effective teaching/learning interactions within the ZPD: that of a scaffold for a building under construction. (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. 26)

Why do they call it scaffolding?

Now let us consider further the ingredients of this special quality of adult-child collaboration. The child is viewed as a building, actively constructing him- or herself. The social environment is the necessary scaffold, or support system, that allows the child to move forward and to continue to build new competencies. (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. 26)

In other words, the child can’t really go meet the mountain himself. He needs a scaffold to get there.

Once introduced by the school of Vygotsky, the term scaffolding soon became very popular:

[Scaffolding] has since become an extremely popular and useful idea in the fields of psychology and education. (Berk & Winsler, 1995, pp. 26-27)

Apparently it became so popular that it worked its way into the standard vocabulary of Charlotte Mason educators. It is also mainstream enough to be listed in The Glossary of Education Reform:

In education, scaffolding refers to a variety of instructional techniques used to move students progressively toward stronger understanding and, ultimately, greater independence in the learning process. The term itself offers the relevant descriptive metaphor: teachers provide successive levels of temporary support that help students reach higher levels of comprehension and skill acquisition that they would not be able to achieve without assistance. Like physical scaffolding, the supportive strategies are incrementally removed when they are no longer needed, and the teacher gradually shifts more responsibility over the learning process to the student.

The Glossary then lists some scaffolding strategies that a teacher could use in a lesson:

- “The teacher gives students a simplified version of a lesson, assignment, or reading, and then gradually increases the complexity, difficulty, or sophistication over time.”

- “The teacher clearly describes the purpose of a learning activity, the directions students need to follow, and the learning goals they are expected to achieve.”

- “The teacher explicitly describes how the new lesson builds on the knowledge and skills students were taught in a previous lesson.”

- “Students are given a vocabulary lesson before they read a difficult text.”

- “Students are given an exemplar or model of an assignment they will be asked to complete.”

We can make a similar list of the jostling that Elsie Kitching describes in her article. The parallels between the lists are eerie:

- A text is broken down and explained so much ahead of time that one would think it was written for a non-native speaker: “the child is jostled with notes and queries and explanations, nay, even with suggestions for making a further supply of notes and queries and explanations on the same lines, till the text becomes a means to an end and not the end which the means are supposed to elucidate” (Kitching, 1921, p. 47)

- The teacher tells the student everything that he will encounter in the coming lesson and steals the joy of discovery before they even begin:

Here is an exercise set to one of Anderson’s “Fairy tales” (The Garden of Paradise),—surely a child’s own kingdom should be sacred to him,—“Obtain information about the monks’ work in ‘Illumination,’ or, the decoration of old-time books.” “On a map of the world find out the positions of the Kossacks, the Pyramids, and the Aurora Borealis. Tabulate these to show which of the winds would see them and find out the cause of the last mentioned.” No joy of discovery left for the little traveller when everything that might occur (or might not!) to him is thus forestalled! (Kitching, 1921, pp. 47-48)

- Students are taught to write by keeping four golden rules in mind. They are told how many paragraphs to write, how to link sentences together and vary their lengths, and to make sure the introductory paragraph contains a key sentence. And don’t forget your forcible closing sentence that must be naturally linked to the proceeding one!

- Students are told exactly what information they are supposed to obtain from the book they are reading:

“The Butterfly” is to lead to,—“From a nature book obtain information about butterflies: stages of growth: how they feed: length of life, etc. Make notes and learn the names and colours of the British kinds.” (Kitching, 1921, p. 48)

The children are not given room to observe or wonder. They don’t get a chance to ask questions or make the knowledge their own.

If Elsie Kitching had access to the The Glossary of Education Reform, she might have included this example of scaffolding as an example of jostling:

When teachers scaffold instruction, they typically break up a learning experience, concept, or skill into discrete parts, and then give students the assistance they need to learn each part. For example, teachers may give students an excerpt of a longer text to read, engage them in a discussion of the excerpt to improve their understanding of its purpose, and teach them the vocabulary they need to comprehend the text before assigning them the full reading.

In June, I claimed that “Charlotte laid out guidelines for how to scaffold lessons to get the most from each course.” Now I am starting to realize the truth. Charlotte laid out guidelines for building without scaffolds.

Are we supposed to scaffold our children by writing difficult words on the board and defining them before reading a living book? Not according to Miss Mason:

A child unconsciously gets the meaning of a new word from the context, if not the first time he meets with it, then the second or the third: but he is on the look-out, and will find out for himself the sense of any expression he does not understand. (Mason, 1989a, p. 228)

As the object of every writer is to explain himself in his own book, the child and the author must be trusted together, without the intervention of the middle-man. What his author does not tell him he must go without knowing for the present. No explanation will really help him, and explanations of words and phrases spoil the text and should not be attempted unless children ask, What does so and so mean? (Mason, 1989f, pp. 191-192)

Are we supposed to scaffold our children by teaching them the rules of composition? Not according to Miss Mason:

But let me again say there must be no attempt to teach composition. Our failure as teachers is that we place too little dependence on the intellectual power of our scholars, and as they are modest little souls what the teacher kindly volunteers to do for them, they feel that they cannot do for themselves. But give them a fair field and no favour and they will describe their favourite scene from the play they have read, and much besides. (Mason, 1989f, p. 192)

The students in the P.U.S. were allowed to meet the mountain in composition by way of reading for themselves a plain text and then narrating orally or in writing without any lessons in composition at all.

Are we supposed to scaffold our children by writing up elaborate lesson plans each day? Not according to Miss Mason:

We come across books on teaching, with lessons elaborately drawn up, in which certain work is assigned to the perceptive faculties, certain work to the imagination, to the judgment, and so on… this sort of doctoring of the material of knowledge is unnecessary for the healthy child, whose mind is capable of self-direction, and of applying itself to its proper work upon the parcel of knowledge delivered to it. (Mason, 1989a, p. 172)

According to Miss Mason, the mother’s lesson preparation is as simple as this:

The teacher’s part is, in the first place, to see what is to be done, to look over the work of the day in advance and see what mental discipline, as well as what vital knowledge, this and that lesson afford; and then to set such questions and such tasks as shall give full scope to his pupils’ mental activity. (Mason, 1989c, pp. 180-181)

No word lists. No learning objectives. Just a double-check to make sure the mountain is there for the child to meet.

Are we supposed to scaffold our children by explaining the important points of a lesson? Not according to Miss Mason:

The Mother must refrain from too much Talk—Does so wide a programme alarm the mother? Does she with dismay see herself talking through the whole of those five or six hours, and, even at that, not getting through a tithe of the teaching laid out for her? On the contrary, the less she says the better… (Mason, 1989a, p. 78)

Are we supposed to scaffold our children by giving them carefully-constructed manipulatives? Not according to Miss Mason:

In elementary schools, the dependence upon apparatus and illustrative appliances which have a paralysing effect on the mind. (Mason, 1989c, p. 243)

So if we follow Mason and not Vygotsky, what does a lesson look like, that builds without scaffolds? Mason explains:

Method of Lesson.—In every case the reading should be consecutive from a well-chosen book. Before the reading for the day begins, the teacher should talk a little (and get the children to talk) about the last lesson, with a few words about what is to be read, in order that the children may be animated by expectation; but she should beware of explanation, and, especially, of forestalling the narrative. Then, she may read two or three pages, enough to include an episode; after that, let her call upon the children to narrate,—in turns, if there be several of them… It is not wise to tease them with corrections; they may begin with an endless chain of ‘ands,’ but they soon leave this off, and their narrations become good enough in style and composition to be put in a ‘print book’!

…

The book should always be deeply interesting, and when the narration is over, there should be a little talk in which moral points are brought out, pictures shown to illustrate the lesson, or diagrams drawn on the blackboard. As soon as children are able to read with ease and fluency, they read their own lesson, either aloud or silently, with a view to narration; but where it is necessary to make omissions, as in the Old Testament narratives and Plutarch’s Lives for example, it is better that the teacher should always read the lesson which is to be narrated. (Mason, 1989a, pp. 232-233)

If we condensed these steps down to a list, a simple “notes of lessons” would look like this:

Step 1: Talk a little about the last lesson.

Step 2: Read pages from a living book.

Step 3: Have the children narrate.

Step 4: Have a little talk at the end.

It’s as simple as that!

Now I am aware of a well-known Parents’ Review article that at first may make it seem like it is not that simple. Helen Wix writes:

Narration, however, is not without its hazards: for example, a keen teacher, in order to ‘improve’ the lesson, may allow herself to talk, to add in the middle of it all some interesting item from her own experience; or she may not have prepared the lesson quite carefully enough—for narration lessons need very thorough preparation—so that she does not notice till too late that there are names and unfamiliar long words which will bother the class. The lesson is therefore stopped for a minute or two while the difficult words are written clearly on the board and a few words of explanation given. Such interruptions do no less than ruin the very best lesson, the thread of interest and intense concentration has been broken and the class will have great difficulty in picking it up again and keeping to it. Even then, the lesson is broken-backed. (Wix, 1957, p. 62)

Does this paragraph from Wix mean that before every lesson, the mother should scan the reading and find any long or difficult words, write them on the board, and teach the vocabulary before the reading? It can’t be, because that would contradict Mason’s statement that “explanations of words and phrases spoil the text.” In fact, what Wix says next shows what her advice really is:

So, all names should be on the board directly the introductory question on the previous lesson has been dealt with, and the children should say them over until their tongues find them easy and familiar. (Wix, 1957, p. 62)

Notice that Wix is just saying to put names on the board, not vocabulary words. So if you’re about to read Plutarch, and your child (or you!) don’t know how to pronounce Æmilius, then go ahead and write it on the board. The point I want to make is that writing the name Æmilius on the board is not scaffolding.

We know from Vygotsky that scaffolding refers to the “help of an adult” so that a child can enter the “dynamic region in which learning and development take place.” But according to Charlotte Mason, the child is born in the region where learning and development take place:

… as the bird has wings to cleave the air with, so has the child all the powers necessary wherewith to realize and appropriate all knowledge, all beauty and all goodness. (Mason, 1911, p. 427)

The very word scaffolding implies a fundamental separation between children and adults. Children are less than persons, and require an adult to jostle them forward. But Charlotte Mason believed that children were fully capable of meeting the mountain themselves.

That doesn’t mean an adult can never help a child. But it means that an adult should help in the same general way that he or she would help another adult. Showing a completed model before a sloyd lesson is not scaffolding. It is the same courtesy I would show if I were teaching a friend to build a model for the first time. When I taught my workshop, I didn’t scaffold the teachers who were there. Why not? Because I fully believed they were capable of learning. Do I believe the same about my children? Then I don’t need to scaffold them either.

I am going to propose something to all of you. How about if we stop using scaffolding as a word to describe elements of a Charlotte Mason education. The PNEU didn’t use this word favorably and by Elsie Kitching’s description of jostling, I can see why. Scaffolding and the use of these modern teaching techniques are stripping “the meeting” away from the student and causing me (the teacher) to run around chasing after an end that is wrong and that will ultimately give me unintended results… just like Old Man Kangaroo. I could avoid all of this extra work of preparing for all of this teaching and relieve a lot of my stress by going back to Mason’s simple teaching principles. Mason’s teaching techniques give us room as teachers to invite the Holy Spirit into our lessons:

Teaching that Invites and that Repels Divine Co-operation.—The contrary is equally true. Such teaching as enwraps a child’s mind in folds of many words that his thought is unable to penetrate, which gives him rules and definitions, and tables, in lieu of ideas—this is teaching which excludes and renders impossible the divine co-operation. (Mason, 1989b, p. 274)

It seems to me that Charlotte Mason would say that building without scaffolds is one thing that invites the Holy Spirit’s cooperation.

That’s the reason why this is so important to me. It’s not just about which teaching strategy is better than another. It’s about how we can pattern ourselves after the method of Jesus. Kitching closes her article with these powerful lines:

Our Lord taught unceasingly, His audiences were the rich, the poor, the learned, the unlearned, the ignorant, the understanding and the slow of heart, but He made no difference in his method and He did not explain unless asked to do so. His appeal was always to mind, and want of will not want of mind was the lack He censured. He taught by parable, by story, and each man took to himself what he needed, some this, some that, others more, others less, but the provision was there for all as in the feeding of the multitudes and there were still ‘baskets full’ over. He left the stories and parables to make their own way because the disciples, the multitudes, had to be made to use their minds that they might ponder for themselves and remember His teaching when the time for action came. (Kitching, 1921, p. 101)

When I teach, I am not trying to get in the zone of proximal development. I am trying to get in the zone of being like Christ.

References

Berk, L. & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. Washington: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Kipling, R. (1912). Just so stories. Garden City: Country Life Press.

Kitching, E. (1921). The meeting. In The Parents’ Review, volume 32 (pp. 44-54, 92-101). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Mason, C. (1911). Children are born persons. In The Parents’ Review, volume 22 (pp. 419-437). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Mason, C. (1989a). Home education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Mason, C. (1989b). Parents and children. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Mason, C. (1989c). School education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Mason, C. (1989f). A philosophy of education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Wix, H. (1957). Some thoughts on narration. In The Parents’ Review, volume 68 (pp. 61-63). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

22 Replies to “Building Without Scaffolds”

Thank you. This is very insightful. And very reassuring. This is what I do, and it is good enough. A wonderful article.

What good research and help this is to me after reading “The Meeting.” Thank you. There’s much to think about and evaluate in my teaching.

Great. Yes. Sometimes, once or twice more than you think, we humans like a long-suffering list of what we need to do. But God says, rest in me, it’s all done in Christ. We look for work, but God says rest. As a teacher, I desperately want to know that my efforts are worthy and not in vain, so I strive daily to achieve “for the children’s sake” … but my stress is unnecessary, rest in Christ, and use good resources and books widely considered “alive”, and the children will climb the mountain in their own way.

Excellent article. I have been thinking the same thing about several widely accepted ways of “doing” the CM method. We’re making things too difficult and getting in the way of our kids learning and obtaining knowledge and skills for themselves.

How reassuring! Thank you!

Interesting differences between building a tower (scaffolding) and meeting a mountain are found in Scripture, too. The Lord was not pleased when the people tried to reach heaven by building a tower. Yet many times we are invited to come to the mountain of the Lord to learn from Him who knows all.

Great insight!

This was a fascinating article and I loved the ending about how Jesus’s taught. Thank you for taking the time to do all this research!

Thank you so much for this rather timely article! These last 4 weeks of trying to prepare lessons the “right” way only led to a lack of peace…and sleep. (Another CM no-no!) Thanks for all the work you put into pulling this information together. It also served as another kick in the pants to finish reading all the volumes. I’m embarrassed to say how long I’ve had them and which volume I’m currently on…

Cannot believe that almost all that I’ve learned in my Grad School and teacher credential program is being deconstructed by Miss Mason! We are taught about scaffolding and its application in lesson planning, just as you mentioned in the essay above. I wish I had known CM before, save me $$$ of tuition fees!

Very interesting article… The Charlotte Mason method is such an organic one! But… where does that leave us philosophically with Andrew Pudewa’s Teaching Writing: Structure and Style units? It looks like a clever programme to winnow writing skills, and is very tempting for me to use. I wonder what Charlotte Mason would have thought of it… too much scaffolding methinks.

Julia,

Thank you for your comment! I think you are right about how Charlotte Mason would have evaluated that particular resource. For a contemporary example of a student who received no formal instruction in writing except narration, please see this article by my daughter.

Blessings,

Art

What a narration! She sure has skill 🙂

I’ve since determined that IEW is too formulaic. I’ve heard it said that people can tell the writing of IEW ‘graduates’ from a mile away. We’ve decided to go in a much more organic and creative direction for our language arts curriculum, as well as embarking on and embracing narration. You certainly have provided a great advertisement for narration!! Thanks!

Thank you for following up, and I am glad this post was encouraging to you!

This is interesting. A few years back, I studied the narration process of Charlotte Mason, and this is the only article where it talks about preparing the lesson by sharing the meaning of the words,

“Do always prepare the passage carefully beforehand, thus making sure that all the explanations and use of background material precede the reading and narration. The teacher should never have to stop in the middle of a paragraph to explain the meaning of a word. Make sure, before you start, that the meanings are known, and write all difficult proper names on the blackboard, leaving them there throughout the lesson. Similarly any map work which may be needed should be done before the reading starts.”

(We Narrate and Then We Know, by E.K. Manders. C.M.T. Volume 2, no. 4, new series, PNEU, July 1967, pgs. 170-172)

Charmayne,

Thank you for sharing this quote from 1967. Based on your research, what is your perspective on this quote and how it relates to the topic of scaffolding in general, and vocabulary development in particular?

Blessings,

Art

Good evening Art,

Well, to be honest, I never questioned the idea until I read this article and reflected on my oldest son who is now in university.

In terms of scaffolding, this quote would make sense to follow. I have had early elementary children who interrupt the reading just to ask what the meaning of a word is, and their ability to attend to the rest of the reading was lacking. Furthermore, their narrations were not as good due to the interruption. So this appears like a good thing to do before a lesson to avoid a break in attention and in ensuring a good narration.

But in light of my knowledge of the Charlotte Mason philosophy and my own personal experience of homeschooling my children, I don’t think this is a good thing to do for my children because I would not be respecting my children and their abilities. It appears to me that I would be easing the job of my child getting the knowledge for themselves by preparing the definitions beforehand. I am essentially making him lazy by doing some of his learning for him. From what I have learned about self-education from Miss Mason, I believe my child should be figuring out the meaning of a word from the context of the passage. Often this is enough, but if my child is still not understanding the meaning of a word, then it is his job to search for the meaning in a dictionary. By doing this, he will remember that word and its meaning much better than if I spoon fed it to him. I do not want to take this responsibility away from my child.

I have a son who is now in university, and I never scaffolded his learning only because I just did not have the time to do so. He turned out to be very well knowledgeable, has a good vocabulary, all because he read a lot of good literary books on his own when he was homeschooled for 9 years. I am pleased to see that scaffolding is not needed in homeschooling. It is a benefit not only to the child, but it is a relief to me as a mother. I am thankful that I do not have to do too much to prepare lessons. With 4 more children coming along, scaffolding would be a overwhelming job for me. I have limited time. I would rather spend the time learning with my children and enjoying life with them, than spending it preparing lessons.

Charmayne,

Thank you for sharing your perspective. The quote from E.K. Manders says, “write all difficult proper names on the blackboard,” which is something that Ashley mentions in her article:

Notice that Wix is just saying to put names on the board, not vocabulary words. So if you’re about to read Plutarch, and your child (or you!) don’t know how to pronounce Æmilius, then go ahead and write it on the board. The point I want to make is that writing the name Æmilius on the board is not scaffolding.

On the other hand, Manders’ remark about vocabulary is somewhat ambiguous: “Make sure, before you start, that the meanings are known.” It doesn’t really say how this is done. It is interesting to compare this remark to what Mason herself wrote:

A child unconsciously gets the meaning of a new word from the context, if not the first time he meets with it, then the second or the third: but he is on the look-out, and will find out for himself the sense of any expression he does not understand. (Mason, 1989a, p. 228)

Your experience with your own children seems to align with Mason’s perspective: children learn words from encountering them in context.

I am glad that this article has helped you see that scaffolding is not necessary for a Charlotte Mason education. It is wonderful that you will spend your time learning with your children and enjoying life with them!

Blessings,

Art

I read this last year but found it again just now when I was searching to see if Vygotsky had ever mentioned Charlotte Mason. Last year, I found it somewhat restrictive as to what Mason herself said about helping children along, although it was an important reminder not to do too much. But this year, I find it somewhat more restrictive.

You see, I just finished reading Vygostky’s writings. And one thing stands out to me. He does not use the term “scaffolding” either. Not using a term does not mean it is not described by either theorist.

I found much to like in Vygotsky but that is not why I am writing. You see, Vygotsky did not feel that scaffolding was The Way to Learn. Neither did he seem to feel that elaborate lesson plans were necessary . What he believed and discovered (found in Mind & Society) was:

– children should not be labeled by their intellectual levels at a particular moment in time based on testing (he felt testing was inadequate) and ONLY what they can do completely unassisted.

– children can do much more than their testing would indicate

– in fact, if one were to come alongside a child and do something together (a craft or a discussion or activity), one would see the child’s capabilities skyrocket because of having someone nearby assisting when necessary

– he felt that this coming alongside and having careful observation of each child and how much they can do with some assistance was a way of helping them learn much more quickly rather than consigning them to what they can accomplish independently based upon testing alone and proceeding from there in the next lesson

– he felt that a teacher should be quite intuitive in this observation and the gentle assistance given to know what a child can do or try and should provide opportunities for a child to realize these capabilities whether the environment or the teacher or his playmates (the social piece) was what was encouraging the child along.

So he believed quite similarly to Mason in careful observation, not labeling children according to their academic performance, stretching them in their capabilities (be it the poetry or literature or …) offering bits of assistance when necessary as a stepping stone to new skills, allowing the environment/parents/social atmosphere of friends to provide new experiences that stretch the child. That empty spot where a child can do so much more with a little assistance was his Zone of Proximal Development. And it wasn’t about the scaffolding. It was about sensing what a child could do. One child could go a tiny bit further whereas another might be able to stretch ahead quite far. Don’t limit a child by their current independent capabilities.

I guess I feel that this article misinterpreted what Mason had to say, determined scaffolding was not a thing because she never used the word, compared scaffolding to Vygotsky (when he never used the word either … authors who wrote about him did), and then mischaracterized Vygotsky’s methods and goals.

I would love more quotes about what Mason did prior to a lesson. This seemed focused only on Kitching, whereas I believe there are other things Mason said and did regarding this. Would you happen to be familiar with those? And you can find Mind & Society online as a free resource to see Vygotsky’s translated writings.

Michele,

Thank you for posting this thorough and thoughtful comment. I would like to respond to your specific points of feedback.

1. You wrote:

I guess I feel that this article misinterpreted what Mason had to say

Could you please provide more detail on this point? I would be interested to hear how you think the author misinterprets Miss Mason. I would also be interested to see any examples you have from Mason’s writings which would falsify the interpretation presented in this article.

2. You wrote:

I feel that this article … determined scaffolding was not a thing because she never used the word

This article does not make an argument from silence. This article compares the method of scaffolding to the method of Charlotte Mason and shows that the two are incompatible. The analysis would still be valid whether or not the term scaffolding was used.

It is important to note that when the term scaffolding was imported into the Charlotte Mason community, it was done so with direct reference to Vygotsky. For an elaboration of this point, please see our podcast episode on scaffolding.

3. You wrote:

I feel that this article …. compared scaffolding to Vygotsky (when he never used the word either … authors who wrote about him did)

This article clearly acknowledges that the term scaffolding was not introduced by Vygotsky himself. This article states:

We have already mentioned the metaphor that has emerged in the literature to describe effective teaching/learning interactions within the ZPD: that of a scaffold for a building under construction. (Berk & Winsler, 1995, p. 26)

Then it states, “Once introduced by the school of Vygotsky, the term scaffolding soon became very popular.”

4. You wrote:

I feel that this article … mischaracterized Vygotsky’s methods and goals

According to Jake E. Stone of Simon Fraser University, “Vygotsky developed his developmental psychological and psycholinguistic theory within a framework of dialectical materialism influenced by the writings of Hegel and Marx.” For example, we are told that according to Vygotsky:

The utterances of an infant under twelve months in age do not involve thinking. Rather, such utterances are predominantly emotional expressions and social calls that, Vygotsky argued (1986), are analogous to the utterances of other primates… Vygotsky himself did not consider children as able to grasp true concepts until adolescence.

Furthermore, according to Vygotsky:

… the child’s potential is not some deep inner nature that blooms when given appropriate nurturing. Rather, the child’s potential is constituted by how the cultural tools she has already appropriated will facilitate her ability to appropriate additional and, perhaps, more abstract cultural tools as she continues to engage within her community.

These views are in radical opposition to Mason’s view that the child is born a person. The child is not born a mere primate who can finally grasp concepts in the teen years. Rather, for Mason, the child is the “eye among the blind.”

5. You wrote:

I would love more quotes about what Mason did prior to a lesson.

You might find these articles on lesson planning to be helpful: “Sharing the Effort To Know” and “Lesson Preparation.”

6. You wrote:

This seemed focused only on Kitching

In Margaret Coombs’s biography of Charlotte Mason, she writes:

For thirty years, Miss Kitching had unobtrusively served Miss Mason as attentive companion and devoted scribe. As director of the PUS and editor of Parents’ Review, she was admired for her breadth of vision and humor as the most knowledgeable interpreter of Miss Mason’s thought.

I shared this assessment of Kitching as “the most knowledgeable interpreter of Miss Mason’s thought,” and hence a reliable guide to how Mason would view the concept of scaffolding.

Thank you for letting us know that some of Vygotsky’s translated writings are available for free online. And thank you for sharing your thoughts here. I look forward to continued dialog.

Blessings,

Art

I am familiar with Vygotsky from grad school and what is troubling about this article, at least to me, is that Vygotsky was not consulted directly, given the reference list. Citing primary sources is essential. The concept of ZPD is not a terrible thing. Serious Christian scholars have gained tremendous insight from it and applied it too.

Dear Paola,

Thank you for sharing your feedback on this article. The main reason that Vygotsky is not quoted directly is that the article is about scaffolding, and as far as we know, Vygotsky himself never used that term. Since the term was developed by Vygotsky’s later followers, it is those later followers who are quoted.

Also I don’t think the main purpose of this article is to say that the concept of ZPD is good or bad. Rather, the main purpose is to say that scaffolding does not align with Charlotte Mason’s philosophy. The mission of this website is to provide an authentic interpretation of Charlotte Mason that does not conflate her ideas with other popular, and even possibly good, educational theories.

Respectfully,

Art