Education for the Kingdom, Part 4: Meditation and PNEU Philosophy

Editor’s note: This article is the fourth in a series of new essays by Dr. Benjamin E. Bernier which demonstrate that Charlotte Mason’s educational philosophy can be characterized as a Christ-centered philosophy of education for Christian discipleship, a unique contribution in the history of Christian and educational thought.

© 2017 Benjamin Bernier

Our previous article introduced two important sources in which Mason articulated her view regarding the role of education as the answer to the crisis of faith overcoming the spiritual life of late-Victorian society. The first was her analysis and response to the novel Robert Elsmere, and the second was her translation and recommendation to parents of a series of apologetic sermons by Rev. Eugène Bersier. These sermons can be characterized as Christ-centered apologetics, in that they make the person and teaching of Christ the core of the apologetic argument demanded by the times.

Mason heartily approved and followed this Christological emphasis, and she recommended that parents make the reading of the Gospels, with a notebook at hand, a continual feature of their own life as well as that of their growing children. This Christ-centered principle was crystallized in Mason’s method for the training of both parents and teachers as we will show in what follows.

As we progress through our chronological examination of key references revealing the theological and apologetic views underlying Mason’s philosophy, we now enter a territory which has more familiar features than the previous references. Therefore, I will only highlight the generally less well-known aspects of this formative period of the developing “PNEU philosophy.”

It is worth noting that the name of the organization was expanded to include National to create the acronym PNEU, which is suggestive of the Greek word πνεῦμα meaning spirit. During this period Mason continued to develop an emphasis on the role of the Holy Spirit in education, which was also reflected in her placing the practice of meditation as one of the key formative features for her philosophy and method. This was evidenced by the practice of Sunday meditations which she incorporated early in the life of the House of Education in Ambleside, as we shall see below.

The early years after the foundation of the PNEU and the publication of The Parents’ Review were years of rapid expansion and development of the work in various directions. Mason moved her residence to Ambleside, in the Lake District, a region then far removed from the busy activity and rapid change characteristic of life in the urban areas where Mason had previously lived and worked. This characteristic of Ambleside can be seen in the first part of Robert Elsmere.

Mason chose the quiet atmosphere of the Lake District because it provided the ideal atmosphere of high living and culture in the context of nature. This unique mix had been acknowledged previously by such romantic poets as Wordsworth as well as other intellectual, artistic, and literary figures.

Initially, Mason suggested opening the House of Education in Ambleside with mothers in mind. She first conceived of it as a place where mothers could come during the holidays for a time of training, instruction, and spiritual refreshment before returning to their busy lives. This can be seen from the first advertisement for the House of Education in The Parents’ Review (Mason, 1891, pp. 76-77). But this original design was quickly superseded by a more practical arrangement in which unmarried girls wishing to become governesses could come to be trained so that they could help mothers in large houses with the education of their children.

But the actual training of mothers was not neglected. It was supplied through the establishment of a three-year reading course called the Mother’s Educational Course (MEC). This was a counterpart to The Parents’ Review School curriculum, which Mason began to develop during the same time period.

In this way, Mason began to supply a subscription-based service providing a curriculum of guided readings with periodic examinations, covering what Mason considered essential subjects divided into four general categories: Divinity, Physiology, Moral Science, and Nature Lore. The first of the four indispensable topics “for every mother who wishes to be thoroughly equipped for her work” was described in the syllabus as:

Divinity. “To help mothers to give their children such teaching as should confirm them in the Christian religion.” (Anson, 1897, p. 463)

Under Divinity we find such books as Dr. Abbott’s Bible Lessons and Mary L. G. Petrie’s Clews to Holy Writ, both of which presented innovative attempts to overcome common obstacles to Bible instruction. For example, there was the challenge of religious instruction in schools serving children from various denominations. There was also the challenge for ordinary readers of the problem of doubts raised by the critics. The first book provided instruction in dialogue form, which could be followed by older children. The second presented the content of the Bible in chronological form. It was an approach and program for the studying the whole Bible in three years, with each book placed in its historical order. This approach was useful for self-education, and Mary Petrie first developed it for her “College by Post,” a scheme for the education of women at home. This could well have been the inspiration for Mason’s own Mother’s Educational Course.

The MEC thus began to fulfill the design Mason stressed in her lectures to ladies of 1886: that ladies and their daughters should be well-read in “books of calibre to give the intellect something to grapple with” in order to prevent the “black offense of unbelief.” Mason did this in two parallel courses, one for mothers and the other for children. The children’s curriculum eventually became the Parents’ Review School, later named Parents’ Union Schools (PUS), which provided what came to be known as a “PNEU education.”

The demand for the children’s curriculum quickly increased due to the convenience it offered, especially to English families spread out through the English empire. These families had to find alternatives for English education while their children were being raised away from England. The only alternative was boarding schools.

Yet even though less visible, the Mother’s Educational Course remained a constant feature of PNEU life until it had to be ended, to Mason’s regret, during World War I. At that time, the cost and availability of paper combined with the demands of the new movement of a “liberal education for all” required the abandonment of some of the earlier emphases that Mason had carried on throughout the years.

The Holy Spirit and Education

We have seen how Mason generally followed the lead of F.D. Maurice in asserting the divine inspiration of mothers, who were seen to be endowed by the Holy Spirit with all the necessary gifts for the “mystery of education.” Another aspect of Maurice’s theology which Mason embraced was his emphasis on the early Christian tradition which asserted the universality of truth as directly related to the person of Christ and the work of the Holy Spirit.

In one of his earlier works, Maurice explained how the teaching of the preface of St. John’s Gospel had inspired some of the early church fathers to develop an attitude of appreciation for any truth found in pagan learning. These fathers saw such articulations of truth as instances in which pagans had recognized, however imperfectly, glimpses of the “true light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world” (John 1:9). This true light is one and the same for all: Jesus Christ, the light of the world.

Not every early father coincided with this tendency. Some saw a danger of compromise and amalgamation, potentially leading the church astray. This view was summarized in Tertullian’s famous dictum, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” Mason, however, can be placed in the first current. She shared the Christian appreciation that all learning refers to God. This can be summarized under another ancient dictum, “All truth is God’s truth,” regardless of the source where it first may be found.

This important emphasis was developed in Mason’s second volume, Parents and Children. The content of this book was first published as a series of articles in The Parents’ Review before it was collected together into a book. Among the early articles in The Parents’ Review, one was especially important as it constituted Mason’s first effort to define the principles of her “PNEU philosophy.” This article should be seen as the antecedent of the synopsis written ten years later.

This article took the form of a creed presented in question and answer format. She later referred to it as “A Catechism Of Educational Theory” (Mason, 1896/1989b, p. 233). In this document, Mason laid down her anthropology, the physiological basis for her philosophy, and she stated for the first time the principle of “the great recognition.” She also discussed the source of the “sustenance of ideas”:

Then the spiritual sustenance of ideas is derived directly or indirectly from other human beings?

No; and here is the great recognition which the educator is called upon to make. God, the Holy Spirit, is Himself the supreme Educator of mankind.

How?

He openeth man’s ear morning by morning, to hear so much of the best as the man is able to bear.

Are the ideas suggested by the Holy Spirit confined to the sphere of the religious life?

No; Coleridge, speaking of Columbus and the discovery of America, ascribes the origin of great inventions and discoveries to the fact that “certain ideas of the natural world are presented to minds, already prepared to receive them, by a higher Power than Nature herself.”

Is there any teaching in the Bible to support this view?

Yes; very much. Isaiah, for example, says that the ploughman knows how to carry on the successive operations of husbandry, “for his God doth instruct him and doth teach him.”

Are all ideas which have a purely spiritual origin ideas of good?

Unhappily, no; it is the sad experience of mankind that suggestions of evil also are spiritually conveyed.

What is the part of the man?

To choose the good and refuse the evil.

Does this doctrine of ideas as the spiritual food needful to sustain the immaterial life throw any light on the doctrines of the Christian religion?

Yes; the Bread of Life, the Water of Life, the Word by which man lives, the “meat to eat which ye know not of,” and much more, cease to be figurative expressions, except that we must use the same words to name the corporeal and the incorporeal sustenance of man. We understand, moreover, how suggestions emanating from our Lord and Saviour, which are of His essence, are the spiritual meat and drink of His believing people. We find it no longer a “hard saying,” nor a dark saying, that we must sustain our spiritual selves upon Him, even as our bodies upon bread.

What practical bearing upon the educator has this doctrine of ideas?

He knows that it is his part to place before the child daily nourishment of ideas; that he may give the child the right initial idea in every study, and respecting each relation and duty of life; above all, he recognises the divine co-operation in the direction, teaching, and training of the child. (Mason, 1892, pp. 357-358)

Although references to these ideas appeared later in other articles by Mason, including her 1896 article entitled “The Great Recognition,” it is only only here in 1892 that the ideas were presented in such detail and with such emphasis as the core of the PNEU philosophy.

This allows us to realize that at the core of the PNEU philosophy is the concept that the primary task of education is the “nourishment of ideas.” This nourishment is directly related to both the work of the Holy Spirit (as the educator of mankind) and the person of Jesus Christ (as The Truth, the Word of life, and the Light of the World). Christ is shown to extend His light and life over every sphere of knowledge and practice in this “redeemed world.”

Meditation

At the time that these articles were being published in The Parents’ Review, the life of the House of Education was beginning to take form, developing these insights and applying them to the spiritual discipline of the House.

Mason would have called her house the “House of the Spirit” if the role of the Spirit as educator of the whole “redeemed human race” (Mason, 1892, p. 358) had been generally understood. But she was concerned that such a title would instead be seen as implying a sectarian view which claimed exclusive inspiration only for itself.

Early in the life of the college, Mason began following the example and precedent of Rev. Alexander Whyte by introducing Sunday afternoon talks. In these talks, Scripture was read and studied in sequence as the subject for meditation for that week. These talks were called ‘Meds’ by the students and were usually led by Mason herself. Sometimes, however, important visitors to the House would lead the talks, and even Alexander Whyte himself conducted a talk when he visited the house during the summer of 1894. He shared with the students his discussion of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Mason had visited Whyte’s church in Scotland in 1875. Whyte had attracted a large class of young people because he believed that good literature was essential for the nourishment of a profound spiritual life. His lectures for young adults at his church therefore combined the teaching of Scripture with the discussion of the spiritual classics of such authors as Dante, William Law, and Jacob Bohem.

The doctrine of education as the nourishment of ideas naturally implies the need for a regular process by which these ideas may be received and digested. This process Mason identified as meditation.

As noted above, Mason related her views on the potency of the idea to the reflections of Samuel Coleridge who had written an influential book called Aids to Reflection. This book emphasized the importance of thoughtful meditation for the development of the spiritual life. I touch on this subject in my thesis:

Mason’s notions regarding meditation follow Coleridge’s lead regarding the habit of ‘reflection’ in relation to the formation of a methodical mind274 which is built up by the discipline of meditation.275 Indeed, the principles upon which Coleridge’s Aids to Reflection was built contain many seminal ideas276 which are consistent with Mason’s views on the value of the study of words and the need for reflection upon the words of revelation for the development of a Christian mind, which she aimed at with her educational philosophy.

The ‘scriptural’ emphasis on knowledge and inquiry, peculiar, according to Coleridge, to the Judeo-Christian Scripture’s view of inspiration, requires a corresponding emphasis on reflection, which Mason prefers to call meditation,277 viewed, not as an emptying of the mind to receive enlightenment beyond thought, but as a filling of the mind with truth, which received in a humble heart, and pursued in a continuous discipline, will lead the soul to grow in knowledge and faith. Also, Mason acknowledges Coleridge’s influence on her views of the nature of ideas as a ‘live thing of the mind’ or ‘a spiritual germ endowed with vital force with power’278 which grows like a seed and acts like ‘meat to the mind’279 Mason developed her educational method built upon these premises, linking these insights directly with the teaching of the Gospel…

274 Mason, Parents and Children, 35.

275 S.T. Coleridge, “Method,” in The Graduated Series of Reading-lesson Books for all Classes of English Schools 5 (London: Longman, Green and Roberts, 1861), 42.

276 See Coleridge, Preface to Aids to Reflection (Liverpool: Edward Howell, 1873), xv-xxi and “Aphorism XI”, 5.

277 Mason makes a distinction between reflection and meditation, suggesting that reflection is the act of ruminating on information received in the past while meditation grows beyond it searching for new insights following ideas to develop new connections and discover new relations of thought. See “Aspects of Intellectual Training” in Mason, School Education, 121.

278 Mason, Home Education, 173.

279 Mason, Parents and Children, 37.

(Bernier, 2009, pp. 133-134)

The metaphor of spiritual feeding becomes more than a figure of speech and necessarily implies a direct connection between the spiritual life and education. In this way, education is conceived of as the process by which we assimilate living and spiritually nourishing ideas, and consequently the task of meditation becomes an essential discipline for every person engaged in any way in the task of conveying living knowledge to others.

It is therefore no surprise that the discipline of meditation reveals the spiritual center of Mason’s training method at the House of Education. The spiritual discipline of the college was strictly followed by all. It included reserving Sundays as a day of rest and spiritual renewal. No ordinary tasks or studies were allowed on Sundays, but instead all students and staff would go every Sunday morning to church and back. They walked together as a group led by the teachers. Later in the afternoon they would gather together for their own “Meds” at Scale How.

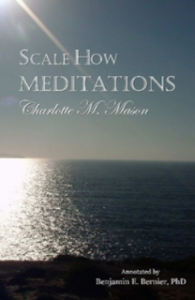

We have a surviving record of a whole year of Mason’s “Scale How Meditations.” In 1898, Mason tried to create a subscription service for the benefit of the old students who, according to her own account, felt the need to keep up the weekly inspiration they derived from the talks. They needed this inspiration since they applied the teaching of the Gospels directly to their challenges as teachers.

Unfortunately the service did not gain enough subscribers to become self-sustained, and at the end of 1898, the mailing of the meditations ceased. The meditations that were published, however, represent Mason’s verse-by-verse commentary on the first seven chapters of the Gospel of John.

These 1898 Meditations on the Gospel of John are extremely important for three reasons:

- They define and elaborate on the importance of meditation for the preparation of all educators.

- They provide explicit declarations of Mason’s interpretation of Scripture.

- They show how Mason derived educational principles directly from the Gospel, principles which she indicated should govern the task of education.

This meditation process was the source from which Mason derived her poetry, which summarized the results of her reflections in poetic form. She published this poetry in the six volumes entitled The Saviour of the World.

Much more content is available than can be covered in a short article. Therefore, I suggest that those who are interested in a deeper look at these subjects should consult Chapter 4 of my dissertation which is devoted to this subject. Even better would be to read Scale How Meditations, the 1898 series on the Gospel of John. After reading these, the Christian foundation and scope of Mason’s PNEU educational philosophy will become very clear.

References

Anson, Mrs. (1897). The Mother’s Educational Course, In The Parents’ Review, volume 8 (pp. 463-468). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Bernier, B. (2009). Education for the kingdom: An exploration of the religious foundation of Charlotte Mason’s educational philosophy. Publisher: Author.

Mason, C. (1891). Notes and Queries. In The Parents’ Review, volume 2 (pp. 75-77). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Mason C. (1892). P.N.E.U. Philosophy. In The Parents’ Review, volume 3 (pp. 349-358). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Mason, C. (1989b). Parents and children. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply. (Original work published 1896)

2 Replies to “Education for the Kingdom, Part 4: Meditation and PNEU Philosophy”

This is so, so helpful. You are right that most of us 21st century Americans have NO idea of the cultural context in which CM was writing and so many of the apparent discrepancies make sense when placed in context. Thank you for sharing the fruits of your labors.

Thank you so much for posting this! I have been curious about the books used in the MEC