New Testament Lessons

In the first article of this series, I proposed a plan to study the New Testament through the higher forms based on the patterns I observed in the historical PNEU programmes and the principles laid out in Mason’s Towards A Philosophy of Education. However, I did not answer the question of “how” the New Testament was studied in the higher forms (III through VI). The purpose of this article is to answer that question.

In the first article of this series, I proposed a plan to study the New Testament through the higher forms based on the patterns I observed in the historical PNEU programmes and the principles laid out in Mason’s Towards A Philosophy of Education. However, I did not answer the question of “how” the New Testament was studied in the higher forms (III through VI). The purpose of this article is to answer that question.

As seen previously, the plan involves two “tracks.” The first track is based on Charlotte Mason’s The Saviour of the World, a poetic commentary on the Gospels. The second track is based on a reading book-by-book through most of the New Testament. Let’s begin with the first track.

Track 1

In the programmes, both tracks are always listed under “Bible Lessons.” That section always begins with the note, “In all cases the Bible text (as given in book used) must be read and narrated first.” So suppose the lesson for the day is The Saviour of the World, volume 4, pp. 134-139. This is poem 51, “The Transfiguration (as remembered).” What is the “Bible text (as given in book used)” that goes with this poem?

Some programmes give a hint: “with Bible passages from index.” If you are using a print version of The Saviour of the World, you would turn to the index at the back of the book and look for poem 51. On page 203, you would see that the Bible passages for this poem are:

St. Matthew xvii. 1-8.

St. Mark ix. 2-8.

St. Luke ix. 28-36.

If you are using a transcribed version of The Saviour of the World, these three passages are listed directly under the title of the poem itself. There is no need to turn to the index.

The next question is which Bible translation to use. The programmes themselves never specify a translation for Bible lessons, with one exception: a small handful of programmes say to use the New Testament in the Revised Version with The Saviour of the World. What is the “Revised Version,” and why is it specified for this one particular element of Bible lessons?

Today, this Bible version is known as the English Revised Version (ERV). The New Testament was published in 1881, and though hardly known in the United States, it remains the only authorized update to the King James Version in England. But I think the handful of programmes that specify this translation do so not because it is authorized, but rather because it is the translation that Mason herself used when she wrote The Saviour of the World. By reading the ERV, it is easier to make connections between the Bible text and the wording of the companion poems.

So suppose the family obtains a copy of the ERV and begins with the New Testament reading for the lesson. The student would begin by reading the following passage (Matthew 17:1-8) (ignore the color-coding for a moment):

And after six days Jesus taketh with him Peter, and James, and John his brother, and bringeth them up into a high mountain apart: and he was transfigured before them: and his face did shine as the sun, and his garments became white as the light. And behold, there appeared unto them Moses and Elijah talking with him. And Peter answered, and said unto Jesus, Lord, it is good for us to be here: if thou wilt, I will make here three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah. While he was yet speaking, behold, a bright cloud overshadowed them: and behold, a voice out of the cloud, saying, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased; hear ye him. And when the disciples heard it, they fell on their face, and were sore afraid. And Jesus came and touched them and said, Arise, and be not afraid. And lifting up their eyes, they saw no one, save Jesus only. (ERV)

Next, the student would read Mark 9:2-8. The text in blue the student would have already read from Matthew. Only the text in purple is new.

And after six days Jesus taketh with him Peter, and James, and John, and bringeth them up into a high mountain apart by themselves: and he was transfigured before them: and his garments became glistering, exceeding white; so as no fuller on earth can whiten them. And there appeared unto them Elijah with Moses: and they were talking with Jesus. And Peter answereth and saith to Jesus, Rabbi, it is good for us to be here: and let us make three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah. For he wist not what to answer; for they became sore afraid. And there came a cloud overshadowing them: and there came a voice out of the cloud, This is my beloved Son: hear ye him. And suddenly looking round about, they saw no one any more, save Jesus only with themselves.(ERV)

Finally, the student would read Luke 9:28-36. The text in blue the student would now be reading for the third time, as it appears in Matthew in Mark. The text in purple and in green would be read a second time, and the text in brown would be new.

And it came to pass about eight days after these sayings, he took with him Peter and John and James, and went up into the mountain to pray. And as he was praying, the fashion of his countenance was altered, and his raiment became white and dazzling. And behold, there talked with him two men, which were Moses and Elijah; who appeared in glory, and spake of his decease which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem. Now Peter and they that were with him were heavy with sleep: but when they were fully awake, they saw his glory, and the two men that stood with him. And it came to pass, as they were parting from him, Peter said unto Jesus, Master, it is good for us to be here: and let us make three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah: not knowing what he said, And while he said these things, there came a cloud, and overshadowed them: and they feared as they entered into the cloud. And a voice came out of the cloud, saying, This is my Son, my chosen: hear ye him. And when the voice came, Jesus was found alone. And they held their peace, and told no man in those days any of the things which they had seen. (ERV)

Now recall that the programmes all say, “In all cases the Bible text must be read and narrated first.” When narration follows these readings, we have a bit of an awkward situation. The student has just read three partially overlapping passages. Should the student try to remember what is specific to Matthew, Mark, or Luke, or rather narrate a continuous and harmonized story? Also, given the normal pattern of narration after a single reading, it is unusual to read the blue text three times before a narration. Could the student start to lose interest the third time the story is read? Would it be better to actually break up the sequence and narrate each passage individually after each is read? Or should there by one big narration of all three passages at the end?

It turns out that there is a powerful solution to that awkwardness. A very small number of programmes point the way. In the section on The Saviour of the World, they say, “Bible passages from index, or from The Gospel History arranged by the Rev. C. C. James.” What is The Gospel History? It is a harmony of the four Gospels, using the ERV translation, published in 1890. Using only the text from the Bible, it synthesizes the text of all the Gospels into a single narrative of the life of Christ. The text is divided into readings. For example, reading number 72 is entitled “The Transfiguration.” A footnote at the bottom of the page indicates that this reading is a synthesis of the following passages:

S. Mark ix. 2-13.

S. Matthew xvii. 1-13.

S. Luke ix. 28-36.

These are almost the same as the verses in the index of The Saviour of the World for poem 51—even the use of Roman numerals. The difference is that The Gospel History places Mark first, and the verse ranges in Mark and Matthew are longer (to go into the second paragraph of reading 72, not covered by this poem). So for the Bible lesson for poem 51, the student would read the first paragraph of reading 72:

And it came to pass about eight days after these sayings, he took with him Peter and James and John his brother, and bringeth them up into a high mountain apart by themselves, to pray. And as he was praying, he was transfigured before them, and the fashion of his countenance was altered, and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment became dazzling, exceeding white, so as no fuller on earth can whiten them. And behold, there talked with him two men, which were Moses and Elijah; who appeared in glory, and spake of his decease which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem. Now Peter and they that were with him were heavy with sleep: but when they were fully awake, they saw his glory, and the two men that stood with him. And it came to pass, as they were parting from him, Peter answered and said unto Jesus, Rabbi, it is good for us to be here: if thou wilt, I will make here three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah. For he wist not what to answer, for they became sore afraid. While he was yet speaking, there came a cloud and overshadowed them: and they feared as they entered into the cloud. And behold, a voice came out of the cloud, saying, This is my beloved Son, my chosen, in whom I am well pleased; hear ye him. And when the voice came, Jesus was found alone. And when the disciples heard it, they fell on their face and were sore afraid. And Jesus came and touched them and said. Arise, be not afraid. And suddenly looking round about, they saw no one any more, save Jesus only with themselves. (James, 1890, p. 72)

Notice how this single narrative elegantly includes important details from all three Synoptic Gospels (illustrated here with the color-coding), with no overlap, no important omissions, and no awkwardness. The student would read this one passage one time, and give a narration after a single reading, which would include all of the full witness about the Transfiguration from the Gospels.

Is this all too good be true? Is it just a coincidence that the reading for the Transfiguration in The Gospel History perfectly aligns with The Saviour of the World? Actually, it is no coincidence it all. It turns out that Mason used The Gospel History as her Bible text when she wrote The Saviour of the World. So when you use The Gospel History, you are using the exact same synthesized text that inspired the poems. It is the perfect match! (The mapping between readings in The Gospel History and The Saviour of the World volume 1 may be found here.)

In addition to facilitating a more natural and elegant narration (since a single narrative is read once, and a single narration is performed), what other benefits are gained from using The Gospel History instead of the Bible passages in the index? Potentially, a better realization of Mason’s aim in setting before the reader the Gospel story:

Let us observe, notebook in hand, the orderly and progressive sequence, the penetrating quality, the irresistible appeal, the unique content of the Divine teaching; (for this purpose it might be well to use some one of the approximately chronological arrangements of the Gospel History in the words of the text). (Mason, 1989f, pp. 337-338)

In my view, we see the “orderly and progressive sequence” more clearly in the harmonized Transfiguration passage from The Gospel History. I grant that not a single historical programme insists on using The Gospel History, so I can’t be dogmatic and say it must be used. But if there is a choice between The Gospel History and the standard Bible text from the individual Gospels, which is the better choice? Admittedly it is a judgement call. But my strong personal recommendation is to use The Gospel History. In addition to the objective reasons I’ve explained above, subjectively, the use of The Gospel History just “resonates” with me. I have led many lessons with it, and it just “feels” like a very smooth, rich, and wonderful way to enter into the truth of God’s Word—and it beautifully sets the stage for the same “feel” that I sense from The Saviour of the World.

OK, so now we have completed the first step—“the Bible text … must be read and narrated first.” Now what? What do we do next?

Forms III-IV

In The Parents’ Review article entitled “Bible Teaching In the Parents’ Union School” by Eleanor M. Frost, the author describes a Form III-IV Bible lesson as follows:

As before, the lesson is connected with the previous one, and then the pupils read from the “Gospel History,” which is the Revised Version, arranged in chronological order. Discussion follows and explanation, the pupils being led to do as much as possible of this themselves. Next, to help them to picture the scenes, to feel and to think, the teacher reads the corresponding poem from Volume II. of The Saviour of the World. (Frost, 1913, p. 520)

We also have this general note from “Miss Mason’s Message” by E. A. Parish:

The passage to be studied is read in the Gospels and then narrated… When the teacher and the children have found out all they can, the verses referring to it in the “Saviour of the World” are read by the teacher and narrated by the children. (Parish, 1923, p. 61)

Don’t worry about the ellipses for now—I will come back to that. If we harmonize Frost and Parish, we may suppose that a narration of the Bible passage precedes the discussion and then a narration of the poem follows the reading of the poem:

- The lesson is connected with the previous one (Frost)

- The passage is read (Frost, Parish)

- The passage is narrated (Parish)

- Discussion follows (Frost, Parish)

- The poem is read (Frost, Parish)

- The poem is narrated (Parish)

The discussion portion seems to be driven by the student, as both Frost and Parish emphasize how students are doing as much of the work as possible. Frost explains why this is so important:

But it is essential that the pupils work for themselves; they must be led to ponder, to meditate, and to reason, for it is true of the spiritual world as of the material, that, what is hardly earned is dearly prized—therefore with their minds must they labour. (Frost, 1913, p. 516)

But even though the student is doing most of the work, the teacher is still present. This confirms to me that the Gospel lesson is best done by the parent and student together, rather than by the older student working completely alone.

The last step is to read and narrate the poem. The poem is not an analytical commentary on the passage. Rather, it helps the student “picture the scenes, to feel and to think.” Its message is personalized and internalized by the narration which follows. The result is a much deeper personal relationship with the Gospel story.

Forms V-VI

Form V introduces an interesting twist. In the article “Bible Teaching In the Parents’ Union,” Frost goes on to describe the Form V-VI Bible lesson as follows:

The New Testament work was the chronological study of part of Christ’s earthly Ministry, and this was taken from The Gospel History, with the corresponding notes from each Gospel in the “Commentary.” For instance, suppose the lesson to be on the healing of Peter’s Wife’s Mother; the pupils would read the story in The Gospel History, then compare the accounts of this miracle in St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke, using the Notes in [J. R. Dummelow’s] The One Volume Commentary, next they would read the corresponding poem in Volume II. of The Saviour of the World. Studying the Gospel stories thus, the pupils get the four points of view about Our Lord and also the illustrative poems which help them to think and feel. (Frost, 1913, p. 521)

Unlike in Form III-IV, the Form V-VI class actually analyzes the differences between the three Synoptic accounts. Although interestingly, the text seems to imply that this analysis is done “using the Notes in The One Volume Commentary.” Now I will share the full Parish quote from “Miss Mason’s Message”:

The passage to be studied is read in the Gospels and then narrated. The children then set to work to understand the passage more fully by comparing the different accounts and by bringing all they know to bear upon it; sometimes the teacher asks questions or points out some new aspect but more often she learns a great deal from the children. When the teacher and the children have found out all they can, the verses referring to it in the “Saviour of the World” are read by the teacher and narrated by the children. (Parish, 1923, p. 61)

I find it fascinating that Parish says the “passage” (singular) is read, but then the “accounts” (plural) are compared. To me, this implies a single passage in The Gospel History, with an awareness of multiple accounts in the separate Gospels.

Parish does not say that the comparing of the different accounts is reserved for Forms V and VI. But if we harmonize Frost and Parish for Forms V-VI, we get the following sequence for a lesson:

- The passage is read (Frost, Parish)

- The passage is narrated (Parish)

- The individual Gospel accounts are compared (Frost, Parish)

- Discussion follows (Frost, Parish)

- The poem is read (Frost, Parish)

- The poem is narrated (Parish)

How are the individual Gospel accounts compared? I think the secret is found by looking at Dummelow’s The One Volume Commentary. The notes on the Transfiguration in the Gospel of Matthew all fit on p. 683. Remember, this is the commentary on Matthew. But observe the following comments on the page:

… it took place at night (see Luke 9:37)

…

it is urged that their eyes were ‘heavy with sleep,’ but St. Luke, who alone mentions this fact, is careful to add that ‘they remained awake throughout’

…

1. After six days] Lk ‘after about eight days,’ either an independent calculation or another way of reckoning.

…

St. Luke alone mentions that the change took place while Jesus was praying.

…

He felt that it was good to be there in such glorious surroundings, and by no means wished to descend to earth again, to begin the fatal journey to Jerusalem of which Moses and Elijah were speaking (St. Luke). St. Mark adds: ‘He wist not what to answer, for they were sore afraid.’

…

This is my beloved Son] Lk ‘This is my Son, my chosen.’

As we see, a significant attribute of Dummelow’s commentary is that it compares the individual Gospel accounts. Why does Dummelow do this? One reason is perhaps to explore the relationships between the eyewitness accounts:

The narrative in St. Matthew and St. Mark is derived from St. Peter. That in St. Luke is largely independent, and may be in part derived from St. John, the only other surviving witness when St. Luke wrote. (Dummelow, 1908/1916, p. 683)

This table shows how seamless this Gospel lesson is with The Gospel History and Dummelow’s The One Volume Commentary:

| With The Gospel History and Dummelow’s The One Volume Commentary | With the standard Bible (ERV translation) | |

| The passage is read | One reading from The Gospel History | Multiple readings from multiple Gospels with some overlap between readings |

| The passage is narrated | A straightforward narration of a single narrative account | A complex narration based on multiple overlapping narrative readings |

| The individual Gospel accounts are compared | Accomplished by reading and reflecting on the commentary | Accomplished by looking at the multiple Gospel accounts and trying to find any differences |

| Discussion follows | No difference | |

| The poem is read | ||

| The poem is narrated | ||

Of course, the right-hand column is doable. But how much more seamless and elegant is the left-hand column? Dummelow’s commentary may be thought of as more analytic, whereas Mason herself said that The Saviour of the World was a synthetic study. The Gospel lesson conducted in this way is thus a wonderful blend of analytic and synthetic thinking. As is characteristic of Mason, it eschews dualisms and extremes.

Track 2

In the second track, individual New Testament books are read from beginning to end over the course of one or more terms. The rotation begins with John, then continues with Acts and most of the epistles. It is important to note that this is happening in parallel with track 1. There is no correlation between the tracks. In any given week, a Form III student might read a passage from John (in The Gospel History) for track 1, and then read an unrelated passage from John in track 2. It is also important to note that the programmes never specify a translation to use for track 2.

As I pointed out in the first article of this series, the lessons in track 2 always involved the use of a commentary. Frost gives us a glimpse of how the track 2 lesson was conducted:

Part of the “Acts of the Apostles” was also studied in much the same way, viz. the reading of the Bible passages, the individual effort to understand fully, stimulated where necessary by the teacher, and then the study of the notes. (Frost, 1913, p. 521)

Based on what we see in the programmes, we can surmise the following sequence for a track 2 lesson:

- The passage is read

- The passage is narrated

- The commentary is read

- Discussion follows

Again, the discussion is primarily driven by the student. Frost explains, with specific reference to Format 5-6:

… the teacher’s work is not so much to teach as to direct; the pupils must search and strive for themselves; her office is to stimulate their thought, quicken their conscience and show them the way of personal study, that when the actual supervision of school days is over they may know how to continue Bible Study for themselves. (Frost, 1913, p. 520)

I love that last clause. As parents, we are preparing children for the day when they will leave home. And it comes sooner than you’d think. One moment they are toddlers; the next moment you are fixing tassels on their cap.

Conclusion

We recall from our first article that Bible Lessons are the formal portion of the student’s education designed to lead him or her to the knowledge of God. Frost also emphasizes this point:

The Knowledge of God. These simple yet profound words of infinite possibility and meaning might stand perhaps with arresting effect at the head of any Bible lesson. They give at once, the essential reason for such a lesson; and who, seeing them, would let the manifold literary but lesser claims of the Bible outweigh its first and greatest, as a revelation of the Divine? (Frost, 1913, p. 514)

Mason frequently uses the analogy of eating to describe the process of feeding on living ideas. When we apply this metaphor to the mode of reading, narrating, and reflecting as laid out above, I am reminded of what Ezekiel experienced:

And he said to me, “Son of man, eat whatever you find here. Eat this scroll, and go, speak to the house of Israel.” So I opened my mouth, and he gave me this scroll to eat. And he said to me, “Son of man, feed your belly with this scroll that I give you and fill your stomach with it.” Then I ate it, and it was in my mouth as sweet as honey. (Ezekiel 3:1–3, ESV, 2016)

Let us feed our youth the scroll of God’s Word. When we serve it to them in this way, I believe they will find it “as sweet as honey,” and it will bring sustenance to their lives.

References

Dummelow, J. (Ed.) (1916). The one volume commentary. New York: The Macmillan Company. (Original work published 1908)

ERV. (1895). The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha: Translated out of the original tongues: being the version set forth A.D. 1611 compared with the most ancient authorities and revised. Cambridge: Cambridge at the University Press.

ESV. (2016). The Holy Bible: English standard version. Wheaton: Standard Bible Society.

Frost, E. (1913). Bible teaching in the Parents’ Union School. In The Parents’ Review, volume 24 (pp. 514-522). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

James, C. (1890). The Gospel history. London: C.J. Clay and Sons.

Mason, C. (1989f). A philosophy of education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

Parish, E. (1923). Miss Mason’s message. In In memoriam, pp. 58-66. London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

19 Replies to “New Testament Lessons”

Thank you so much, Art, for sharing your research and for linking to “The Gospel History”, as well as all that color-coding! I have so been looking forward to this second article after having read your first.

We have been enjoying our gospel study together with “Saviour of the World” and I’m now excited to begin an even richer study with our young men!

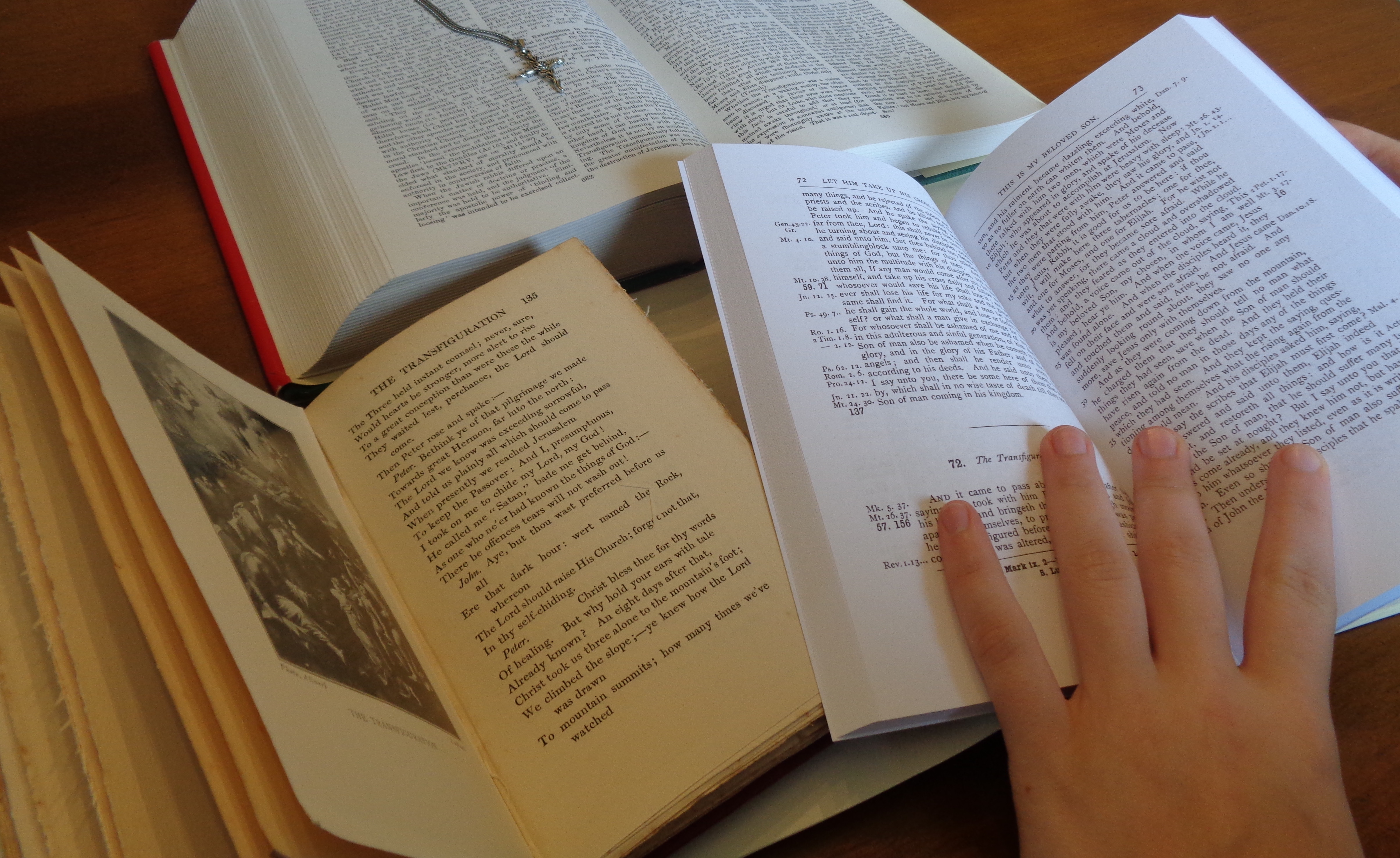

Thank you for all of this work. What books do you have in the picture?

You’re welcome, and thank you for asking! On the left of the foreground is The Saviour of the World volume 4. On the right of the foreground is The Gospel History. In the background is Dummelow’s The One Volume Commentary. All books are open to the text on the Transfiguration.

I continue to be thankful for your steadfast dedication and devotion in bringing living ideas and the pathway to bring living and truth filled ideas into our lives, so we may share them with our family. I am just beginning Form III with my eldest daughter- what a delight to be so well equipped.

Thank you, Art. The information about The Gospel History has been the missing link for me. I had been stymied by the thought of reading the same episode multiple times. The use of a harmonized account is an ‘aha!’ moment. Appreciate all your research into teasing this out and sharing it with us.

Should students be doing a reading from both track 1 and track 2 on any given New Testament Bible lesson day? I’m trying to understand how this schedule looks in any given week. The lessons were only 15 minutes and each week they would have 2 New Testament lessons and 2 Old Testament lessons…right? I guess there is a fifth day that could be used (we use it to read the upcoming Sunday gospel). So, would you recommend doing track 1 on one day and track 2 on the second New Testament day? I know you stated above that on any given day a student might read two unrelated sections from the same book, but I can’t see how both tracks could be covered in a single lesson if we stick to the timetable. Yet, if we only have one lesson from each track each week, then is it even possible to cover the given material? Am I missing something? Thanks for all your invaluable work on this!

Dear Sarah,

Thank you posting this excellent question. Volume 20 of The Parents’ Review (1909) includes a Parents’ Union School time-table for Forms III-IV that allocates 20 minutes for Old Testament lessons on Monday and Thursday and 20 minutes for New Testament lessons on Tuesday and Friday. The lesson time is expanded from 20 minutes to 30 minutes for Forms V-VI. It seems to me that track 1 could be done on Tuesday and track 2 could be done on Friday. These lessons should easily fit in the allocated time. I am going to update my article so that instead of saying “On any given day,” I will say “In any given week.” Thank you for taking the time to think through this and for refining my own understanding.

Blessings,

Art

Thank you Art! I’m curious now…did the time-table specify what the students were doing on Wednesday or Saturday since they would have Bible on those days too? Also, how would you feel about including younger students (form I and form II) in the SOTW lesson day? I’m considering doing this just so we can have at least one day of Bible time together, and maybe after a year of doing it together my older students would feel more comfortable doing it alone.

Sarah,

The time-tables show four days of Bible lessons. Two are explicitly designated New Testament and two are designated Old Testament. The two New Testament lesson days presumably map to track 1 and track 2 in this article. For information about the Old Testament lessons, please see this article.

I would not recommend that you have your children do these lessons alone, even if they have grown comfortable with the material. I think the interactions between parent and young adult over The Saviour of the Word are valuable and worth making time for.

Regarding younger students, remember that these are Bible lessons, not family devotions. I think the younger children benefit from the Bible lessons that Mason envisioned for Forms I and II. I wouldn’t say that young children need to leave the room when the upper-level Bible lessons take place. However, these particular lessons are geared towards your young adults. To enrich family time together, it may be advisable to have family devotions and family worship that is accessible to all ages.

Blessings,

Art

I forgot to ask my other question! What do you do on the days when there is ONLY a poem and no reference to the Gospel History? For example, Poems II, IV, and VII in SOTW Volume I do not have a Gospel History reference. So, on those days, do we simply read the poem and narrate? Thanks again.

Yes, exactly. The programme specifies the page ranges in The Saviour of the World. That makes it clear that the SOTW is “driving” the schedule, not The Gospel History. That means that some days will only have a poem. But there will be plenty of other times during the week that the student will be exposed to the Bible, including during his or her personal devotions.

This article was super helpful, along with the ADE podcasts 13 & 105! Thank you, Art!

Hi Art! Thank you so much for this wonderful guide to teaching Bible! I was at the conference last weekend and I have a copy of what form III-IV does for Old Testament History terms but I didn’t get to copy the coordinating terms for the New Testament History for forms III-IV Any chance you could add those charts to this post? Or are they posted somewhere else? They are a great reference, thank you!

Rachel,

I believe this article contains what you are looking for: https://charlottemasonpoetry.org/new-testament-studies-in-the-higher-forms/

Regards,

Art

Super super helpful Art! Thank you, once again for the clarity! Appreciate everything you continue to do!

Art, this is so helpful. Thank you for all your work. Would the pace be 1 poem per week? I notice that Volume 2 includes 50 poems. We have 33 weeks of school, plus our 3 weeks of exams. Would Charlotte have continued the book in the following school year?

Julie,

Charlotte Mason’s design was for each volume to be completed in a year. To see how each volume was broken out by term, please see my companion article. This means covering more than one poem on certain weeks. This is possible since some poems are short or apply to common passages of Scripture.

Blessings,

Art

Thank you so much for your work and generosity sharing your findings with us. This year, my Form III student will be studying 1 & 2 Kings for OT and Acts for NT. I hope that’s the right way to coordinate those studies. If so, I’m wondering if there is a Costley-White OT History available that would cover the OT part. I’m also wondering if the Book of Acts is included in the Gospel History, or if the years Acts is studied the Gospel History is not used, and also how to coordinate Saviour of the World with those sections. Sorry so many questions and thank you so much for any help you may be able to offer.

Erika,

Thank you for reading this article and sharing your questions. Unfortunately, I don’t have access to H. Costley-White’s Old Testament History, so I can’t speak to how that series covers 1 & 2 Kings. The Gospel History does not cover Acts and was assigned to be used in conjunction with The Saviour of the World. It does not take the place of the study of Acts, but is rather a second and independent stream of New Testament lessons.

Blessings,

Art