Reflections on The Saviour of the World Volume 6

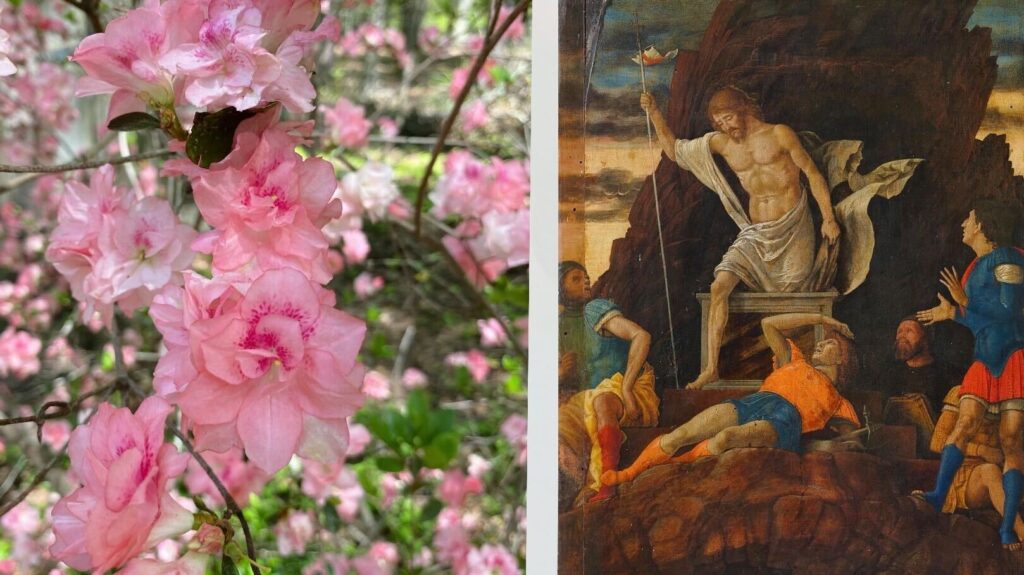

Book I Poem I

“But, now, Hope rose transcendent as a god,

Compelling and fulfilling. But what art

Could show that radiant form or who portray;

Or shape in words the Resurrection joy?”

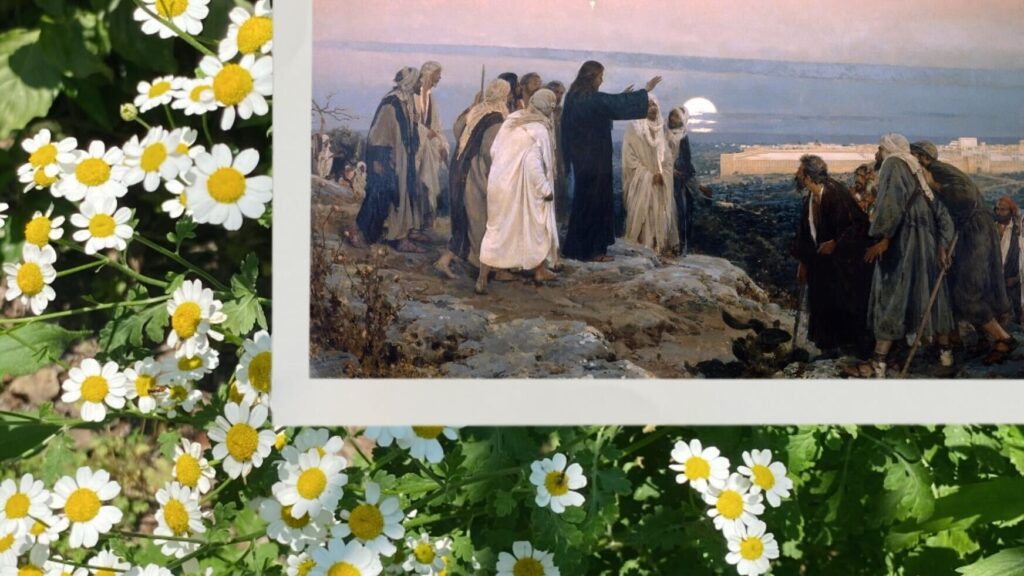

For Charlotte Mason, the raising of Lazarus was a foreshadowing of the greater miracle that was yet to come, the miracle we celebrate today. For on Resurrection day, “Hope was revealed … Shadow of Death withdrawn.”

Today we begin our journey through Mason’s sixth volume of poems, entitled “The Training of the Disciples.” Read or listen to the first poem of the volume, which fittingly points to the Resurrection of Christ. (You can find it here.) And may you have a blessed time with family and friends celebrating and remembering our Lord on this most special day.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem II

“We say some things on our own, by ourselves, where there is no power that inspires us to speak,” wrote Origen of Alexandria in the 3rd century. “But there are other things that we say when some power prompts us (as it were), dictating what we say, even if we do not fall completely into a trance and lose full possession of our own faculties, but seem to understand what we say. Now, it is possible for us, while we understand what we say on our own, not to understand the meaning of the words that are spoken.”

How could a person not understand the meaning of the words that he speaks? When could such a thing happen?

According to St. Augustine, it can happen when one holds a sacred office. He cites the Apostle John as his authority, who “attributes this power to the divine sacramental fact [of being] the high priest.”

And so Origen continues: “This is what happened in the case of Caiaphas the high priest. He did not speak on his own, by himself, nor did he understand the meaning of what he said, since it was a prophecy that was spoken.”

The prophecy was recorded in John 11:51–52. The high priest did not understand its meaning, but Charlotte Mason did. Read or hear her convicting and inspiring poem “What do We?” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem III

“Let them grow up, too, with the shout of a King in their midst,” writes Charlotte Mason in Parents and Children. “There are, in this poor stuff we call human nature, founts of loyalty, worship, passionate devotion, glad service, which have, alas! to be unsealed in the earth-laden older heart, but only ask place to flow from the child’s. There is no safeguard and no joy like that of being under orders, being possessed, controlled, continually in the service of One whom it is gladness to obey.”

What of those who had the King physically in their midst? In John 11:54 we read that Jesus went to a city called Ephraim. “Blest men of Ephraim who saw the Light!” reflects Miss Mason. She imagines how they would have greeted the King and His twelve peers. Pennons, broideries, and costly carpets? Surely that is what founts of loyalty and passionate devotion would set out.

But no. “No blazonry of heralds, trumpets’ blare, proclaim the news that a Great One has arrived. Scarce any turned to watch the meek procession of the Lamb.” Read or hear Mason’s poem “He tarried at Ephraim” which brings fresh light to a single verse, and unseals the earth-laden heart. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem IV

I will never forget the first time I entered the hall of the seven virtues in the Uffizi Gallery. I looked intently at the first painting, and then the second. “Paintings,” I thought. Another, and another. Until finally I reached the end of the hall, and then I gasped. I could not simply say to myself, “Painting.” For I was standing before something that was more than a painting.

“Everybody else’s Fortitudes announce themselves clearly and proudly,” writes John Ruskin. “They have tower-like shields, and lion-like helmets—and stand firm astride on their legs,—and are confidently ready for all comers.”

Not so the Fortitude of Sandro Botticelli. “Botticelli’s Fortitude is no match, it may be, for any that are coming. Worn, somewhat; and not a little weary, instead of standing ready for all comers, she is sitting,—apparently in reverie, her fingers playing restlessly and idly—nay, I think—even nervously, about the hilt of her sword. For her battle is not to begin to-day; nor did it begin yesterday. Many a morn and eve have passed since it began—and now—is this to be the ending day of it? And if this—by what manner of end?”

Charlotte Mason read these words of John Ruskin in Mornings in Florence. She alluded to them in Ourselves Book II in her chapter on Fortitude.

When speaking of humility, Mason quoted William Law: “There never was nor ever will be, but one humility in the whole world, and that is the one humility of Christ.” Perhaps there is only one fortitude also. When Mason wrote of the fortitude of Christ, she cited Ruskin again. And she cited Botticelli again. And I know why. Because it is really more than a painting. Read or listen to Mason’s poem on the fortitude of Christ here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem V

“There is no sin, no vice that gives one such a foretaste of hell in this life as anger and impatience,” wrote Catherine of Siena. “[The impatient] are unwilling to bear or tolerate their neighbors’ shortcomings; they don’t even know how to! Anything that is done or said to them sets them flying, their emotions stirred to anger and impatience like a leaf in the wind!”

“There is no sin, no vice that gives one such a foretaste of hell in this life as anger and impatience,” wrote Catherine of Siena. “[The impatient] are unwilling to bear or tolerate their neighbors’ shortcomings; they don’t even know how to! Anything that is done or said to them sets them flying, their emotions stirred to anger and impatience like a leaf in the wind!”

In recent years, Dr. S. M. Davis has spoken at length about the destructive impact of anger within families. “Rebellion in youth seldom goes away until parents deal, not just with anger, but with their spirit of anger,” he explains. He points to the moment in Luke 9 when James and John ask if they should “command fire to come down from heaven, and consume” the Samaritans. Jesus rebuked not only their anger, but also their spirit of anger: “Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of” (Luke 9:55).

Many justify anger when it is expressed as righteous indignation. And when is indignation ever more righteous than when the honor of Christ is at stake? Charlotte Mason explores this question in her poem entitled “The Samaritan Village.” What is the root of anger, and what is its fruit? Examine your spirit as you read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem VI

In her book Restless Devices, Felicia Wu Song describes her emotions after reading these words of Tish Harrison Warren:

In church each week, we repent together… Confession reminds us … our failures or successes in the Christian life are not what define us or determine our worth before God or God’s people. Instead, we are defined by Christ’s life and work on our behalf. We kneel. We humble ourselves together. We admit the truth.… And then—what a wonder!—the word of absolution: “Almighty God have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life.”

Felicia Wu Song recalls that these words made her “slam on the brakes.” She explains: “To run across such an account of Christian confession and absolution is to come up against what feels so stunningly like an alternate universe. This description brings into sharp relief the vast distance between the posture we practice when we are steeped in the social imaginary of our permanent connectivity and the posture that Christian spirituality encourages. Our typical digital practices of keeping up, grasping for attention, and seeking the reward of affirmation begin to feel paltry and thin against the sheer magnificence of what is promised in the ritual of confession: to be invited to freely admit our failures and discover that we are still loved and welcomed.”

Sometimes our words of confession are impromptu and extemporaneous. And sometimes our words follow a form, and ancient or modern prayer. Charlotte Mason’s poem “I have transgressed” might well be one such form. Her beautiful verses give us the words we need “freely admit our failures.” Read or hear them here, and then delight in the knowledge that we are still loved.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem VII

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke describe a man who says, “Lord, I will follow You wherever You go.” To this profession of faith, our Lord responds, “Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay His head.”

How does this man respond? Leon Morris notes that “The scribe’s reaction is not given, but certainly the cost of discipleship is brought clearly before him.”

Morris goes on to explain that “John uses the verb for lay when he is speaking of Jesus bowing his head on the cross (John 19:30); there the Master found the resting place that he did not have throughout his ministry.”

The cost of discipleship is brought before us too. How will we respond? Consider with Charlotte Mason in her poem on this verses here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem VIII

The past 80 years have seen a growing interest among believers and scholars to better understand the relationship between Jesus Christ and the Judaism of His day. It has become increasingly clear to many that Christ was an observant Jew who held the Torah in the highest regard. One verse in particular, however, has proven especially difficult to reconcile with this view: Matthew 8:22, which reads, “But Jesus said to him, ‘Follow Me, and let the dead bury their own dead.’”

In 1968, German scholar Martin Hengel made his bold declaration about this verse. He claimed that it represented “not only an attack on the respect for parents that is demanded in the fourth commandment but also at the same time it disregarded … works of love, which … had their basis in the Torah.” Christ, he insisted, could not have loved the Torah if He could strike so deeply at the heart of its commands.

In 2000, however, British scholar Markus Bockmuehl questioned Hengel and the consensus that had formed around his view. Bockmuehl pointed to prophetic examples, such as Ezekiel, who was not allowed to mourn for his wife (24:15–27). And he noted the provision in the Torah for the Nazirite, who could not “not make himself unclean even for his father or his mother … because his separation to God is on his head.”

When Jesus was disputing with the Pharisees about the Sabbath, He said, “Have you not read in the law that on the Sabbath the priests in the temple profane the Sabbath, and are blameless? Yet I say to you that in this place there is One greater than the temple.” In the same way, prophets and Nazirites left the dead to bury their own dead, and yet were blameless. And now there is One greater than prophecy or separation.

Charlotte Mason’s poem “Follow Me!” explores the tension of conflicting loyalties raised by this verse. Read or hear her words here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem IX

“Every Christian is called to a life of renunciation,” writes Fr. Vassilios Papavassiliou in his commentary on the Ladder of Divine Ascent. “It is clear, then, that renunciation is not exclusive to monasticism but is an intrinsic part of being a Christian… Christians renounce the world by living for something other than the world. By living thus, we become the light of the world.”

But there is another step in the ladder after renunciation, a step called detachment. “In monastic life,” he explains, “detachment naturally follows renunciation. Having abandoned the world, the monk must guard his heart against yearning for what he has forsaken; he must look not back, but forward. Otherwise, grief and regret will overcome his spirit. Eventually he will come to resent his vocation and see it as an imprisonment and a wasted life, because he has not yet let go of his worldly desires.

“For others, too, detachment is integral to Christian living. I have heard married men and women complain that they married too young, that they did not have the opportunity to do the things they dreamed of, that they have missed out on something because they had to sacrifice their will and desires for the sake of their children or spouse. If the monk, having vowed to live a life of utter dedication, is not to look back, should not married couples observe the same rule? ‘No one, having put his hand to the plow, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God’ (Luke 9:62).”

Charlotte Mason offered her own reflections on this powerful verse in the Gospel of Luke. I invite you to consider the place of detachment in your life as you read or listen to her poem “Fit for the Kingdom” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem X

“The mission of the Twelve is recorded in three Synoptics,” explains Ralph Earle, but “the sending of the Seventy only in Luke. This is in keeping with the point of view of this Evangelist. [Alfred] Plummer puts it this way: ‘This incident would have special interest for the writer of the Universal Gospel, who sympathetically records both the sending of the Twelve to the tribes of Israel (11:1–6), and the sending of the Seventy to the nations of the earth.’”

“In Perea,” he continues, “where these servants of Christ were sent, the population was more Gentile than in Judea. Yet it was predominantly Jewish. While nothing is said about the Gentiles in the instructions to the Seventy, neither is there any prohibition against preaching to them, as there was in the case of the Twelve (Matt. 10:5–6).”

In his volume The Gospel History, C. C. James places this sending of the Seventy shortly after the raising of Lazarus. Charlotte Mason follows James’s chronology and explores the expending mission of our Lord in her poem “The Seventy are sent forth.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem XI

Some poems have a musical quality that is better sensed, I think, when heard rather than read. Something about sound of the words when they are carefully spoken adds a new dimension to the meaning. Charlotte Mason’s poem “The Charge” is one such poem.

Our Lord had said, “The harvest truly is great, but the laborers are few; therefore pray the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into His harvest.” Then He answered His own prayer. Seventy laborers were sent out to the field in a most unusual manner. That mystery is illuminated in verse. Why not listen to it today, read by Antonella Greco. Hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem XII

“Doom to you, Chorazin! Doom, Bethsaida! If Tyre and Sidon had seen half of the powerful miracles you have seen, they would have been on their knees in a minute.” With these words, Eugene Peterson captured the sense of Christ’s words in Matthew 11:21 and Luke 10:13.

Today, “the exact location of Chorazin is unknown, but it clearly was near the northwest corner of the Lake of Galilee,” explains Ralph Earle. “Its very disappearance is a testimony to Christ’s judgment on it. The same can be said for Bethsaida, which was located on the east bank of the Jordan River where it flows into the Lake.”

In her poem on this passage, Charlotte Mason wrestles with the implications of this passage. Does the Lord judge cities as well as individuals? History seems to provide our answer. Read or hear Mason’s thought-provoking poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem XIII

In True to Our Native Land, Stephanie Buckhanon Crowder points to truths in the Gospel of Luke that we are likely to miss. She explains the sending of the seventy as follows:

At 10:3–16, Jesus gives instructions regarding a ministry that was also dependent on hospitality. His directives to the seventy provide a harsh window into the life of a disciple. It is an underground life whose journey toward God did not allow for familial or professional attachments or many private possessions. A person who risks her life in following Jesus must rely on the mercy of others, just as she surely had to rely in every circumstance on the mercy of God. It is a chance slaves were willing to take for freedom. It is a chance believers must take in order to be free and set the captive free.

Why would believers take such a risk? Charlotte Mason explains in her poem on the return of the seventy: “Whose name is writ in heaven meets no annoy.” Read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem XIV

In his 1983 book The second Christianity, John Hick describes the faith of the Old Testament prophets:

God was known to them as a dynamic will interacting with their own wills; a sheer given reality, as inescapably to be reckoned with as destructive storm and life-giving sunshine or the fixed features of the land or the hatred of their enemies and the friendship of their neighbours. He was not to them an inferred reality but an experienced reality.

Dr. William Lane Craig points to these words as an explanation of the idea that we “can know that God exists wholly apart from arguments simply by experiencing him.” In fact, warns Craig, “there’s the danger that arguments for God could actually distract our attention from God himself.”

Perhaps this is part of what Jesus had in mind when He said, “I thank You, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that You have hidden these things from the wise and prudent and revealed them to babes.” And so Dr. Craig invites us: “If you’re sincerely seeking God then God will make his existence evident to you.” Charlotte Mason invites too, in her poem “I Thank Thee, O Father!” Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book I Poem XV

Charlotte Mason had many ways emphasize the knowledge of God. She called it “the chief part of education,” and said it is “first in importance, is indispensable, and most happy-making.”

Charlotte Mason said the knowledge of God is the “principal knowledge,” the “fundamental knowledge,” which is “before all and including all,” and is to be “put first.” In terms of method, it is “to be got first-hand through the sacred writings.”

In her poems, however, she assigns a new superlative to the knowledge of God. She called it “The ultimate Knowledge.” And while the sacred writings are indeed our primary means of receiving this grace, we also need a light. Two lights, in fact. “That they are One, is our eternal gain.” Read more here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XVI

The first chapter of Essex Cholmondeley’s biography of Charlotte Mason is entitled “Preparation.” The most poignant paragraph of this chapter occurs on page 5:

The strain of poverty told upon the health of Charlotte’s beautiful mother and in 1858 she died. Mr Mason never recovered from this loss. He died soon afterwards, leaving Charlotte at the age of sixteen alone in the world. A friend gave her a home for a time; she was entirely without relations and without means, and she passed through a period of great desolation. In her mind remained one idea: she knew that ‘teaching was a thing to do, and above all the teaching of poor children.’ When she was eighteen she took the first step towards her life’s work.

It is hard to imagine what the young Miss Mason experienced during this time of desolation. While her future was hanging in the balance, she made a choice that would eventually touch the hearts of families and educators all over the world for generations to come. What gave this young sixteen year old the power to move forward?

On page 180, Cholmondeley describes a poem Miss Mason wrote called “Rest.” According to Cholmondeley, the poem was “the outcome of the bereavement caused by the loss of [Mason’s] parents.” The poem has a mystical quality and may even be describing a mystical experience from Mason’s youth. The last stanza of the poem includes these words in quotation marks (italicized by Cholmondeley):

As one is comforted, Whom comforteth his mother!

The words seem to be adapted from Isaiah 66:13. The implication is clear. God took the place of mother and father for this young girl, so that our lives and families could one day be blessed. Read or hear the full poem “Rest” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XVII

In the Gospel of Matthew we read these words of Christ: “Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light.”

The saying presupposes that we need rest; but why are we weary? And the saying indicates that we receive a yoke; but what is it?

The answer to these questions are prayerfully explored by Charlotte Mason in her poem “Come unto Me.” Read or listen today and consider a new vision of rest. The poem may be found here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XVIII

Six years ago I invited readers of Charlotte Mason’s poetry to consider and reflect on a small set of poems I selected for Lent. I shared my own reflections on a poem each week. Now in our journey through the sixth volume of Mason’s poetry, we have reached her piece entitled “Restlessness.” Here’s how I described it those years ago:

The haunting way this poem brings out the feeling of restlessness is made all the more powerful to me by how clearly it rings true in my experience. “We wake in the night watches, And fear and shame wake too”—what a sad state when one awakens in the dark and feels palpable fear and shame in that same darkness? One fear, two fears are tolerable. But “A thousand little fears”? Of course we then shake like the leaves of an aspen tree. So many fears we could never control them. Indeed nothing under the sun could answer us.

And yet this poem indicates that amidst fear and shame, there is a place of peace. But not just any kind of peace. The final image of the poem—that of a child falling asleep—gives me a pang each time I read it. Could such peace be possible for me? Really?

As I read my words from six years ago, the questions still resonate with me. But again and again I have been pointed to the answer Mason provided. After all, it is the answer Jesus provided. “Assuredly, I say to you, unless you are converted and become as little children, you will by no means enter the kingdom of heaven.” Can I have the faith and trust of a child? Poems like this one from Miss Mason point the way. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XIX

“Then I saw in my dream, that when they were got out of the wilderness, they presently saw a town before them, and the name of that town is Vanity; and at the town there is a fair kept, called Vanity Fair. It is kept all the year long.”

So begins one of my favorite sections of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. The story haunts me.

“And moreover, at this fair there is at all times to be seen jugglings, cheats, games, plays, fools, apes, knaves, and rogues, and that of every kind.”

The pilgrims had to pass through this fair, otherwise they ”must needs go out of the world.” But they were not welcome there. They did not fit in. Their raiment, their speech, their values set them apart.

“One chanced, mockingly, beholding the carriage of the men, to say unto them, ‘What will ye buy?’ But they, looking gravely upon him, said, ‘We buy the truth.’”

Charlotte Mason also passed through this fair. She found what the pilgrims were looking for. This poem will stay with me forever. Read or hear “At the Fair” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XX

In Luke 10:21, we read that “Jesus rejoiced in the Spirit.” According to James R. Edwards, “Jesus allowed such apertures into his self-consciousness only rarely and on guarded occasions, and only then within the confines of his closest confidants.”

In this moment of joy, Jesus “turned to His disciples and said privately, ‘Blessed are the eyes which see the things you see.’” N. T. Wright explains this moment:

In the same moment of vision and delight, Jesus celebrates what he realizes as God’s strange purpose. If you needed to have privilege, learning and intelligence in order to enter the kingdom of God, it would simply be another elite organization run for the benefit of the top people. At every stage the gospel overturns this idea. Jesus sees that the intimate knowledge which he has of the Father is not shared by Israel’s rulers, leaders and self-appointed teachers; but he can and does share it with his followers, the diverse and motley group he has chosen as his associates. God, says St Paul, chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, the weak to shame the strong.

Charlotte Mason reflected on this moment of joy shared between Christ and His child-like disciples. Read or hear “Happy Ye!” here.

@artmiddlekauff

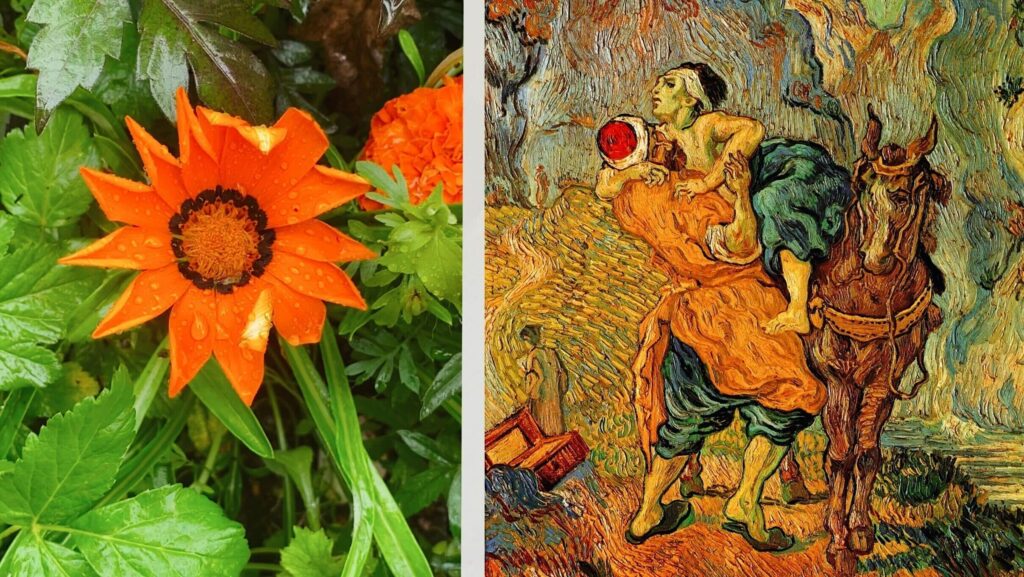

Book II Poem XXI

When John Wesley wanted to describe the state of Adam before the Fall, his meditation led him to one word: love. “Love filled the whole expansion of [man’s] soul; it possessed him without a rival. Every movement of his heart was love.”

We were created to love. So when Jesus asked a lawyer, “What is written in the law? What is your reading of it?” His answer was similar: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind,’ and ‘your neighbor as yourself.’”

But Adam fell. And so, explained Wesley, “Love itself, that ray of the Godhead, that balm of life, now became a torment.”

The lawyer knew that love was the ray of the Godhead. But he was fallen. And so to justify himself, he asked, “And who is my neighbor?”

Read or listen to Charlotte Mason’s poem as she explores the prologue to one of the greatest parables ever told. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XXII

Charlotte Mason’s advice on time management is profound. At the heart is the idea expressed in Home Education: “there is no right time left for what is not done in its own time.” Only when every action has its time can we feel the peace of the pendulum described in Ourselves: “you are only required to give one tick at once, and there is always a second of time to tick in.”

Armed with this wisdom we can put down inclination and instead do our duty. As she explains at length, again in Ourselves:

Now, the eager soul who gives attention and zeal to his work often spoils its completeness by chasing after many things when he should be doing the next thing in order… It is well to make up our mind that there is always a next thing to be done, whether in work or play; and that the next thing, be it ever so trifling, is the right thing; not so much for its own sake, perhaps, as because, each time we insist upon ourselves doing the next thing, we gain power in the management of that unruly filly, Inclination.

The one who has mastered that unruly filly, Inclination, may have to travel from point A to point B. There is only one right time for the journey and that time is today. There is no other right time to complete the errand. So this one insists on doing only the next thing.

And then he passes a man by the side of the road in desperate need. Is this man my neighbor? Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s pastorally profound poem on the Good Samaritan, and see the other side of her beautiful advice on managing our time. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XXIII

“We are all susceptible to putting God second and ministry first,” wrote Shane Idleman. “If we’re too busy to cultivate a prayer life that places God first—we’re too busy. Men would live better if they prayed better. We’re often too busy because we’re doing too much.”

I wonder sometimes if Mary of Bethany felt a little guilty while her sister was doing all the work. Did she get that unsettled feeling that she should be helping out? Could she sense the resentment that was brewing in Martha’s heart?

In the Gospel of Luke, we find that Mary was vindicated by the audible voice of our Lord. But we aren’t shown Martha’s response. Charlotte Mason gives voice to her prayerful imagination in today’s poem. Read or hear what Martha may have thought when she heard that only one thing is needful. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XXIV

In her book The Dialogue, Catherine of Siena offers a message for restless hearts: “Without [God] they could never be satisfied even if they possessed the whole world. For created things are less than the human person. They were made for you, not you for them, and so they can never satisfy you.”

In Psalm 17, David points to what actually can satisfy us: “I shall be satisfied,” he avows, “when I awake, with thy likeness.” But is this peace reserved for the next age, or can we experience it in this?

In Charlotte Mason’s poem “Satisfied,” she shows us how “unquiet heart enters green place of peace where none molest.” There, in the words of Catherine’s Dialogue, “they … feel [God] in their souls by grace and are satisfied.” Read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XXV

The Rev. Francis Lewis was a friend of Charlotte Mason in life and in death. He was said to be “a devoted friend and worker … in everything where Miss Mason’s ideals were concerned,” and in 1923 he assisted at her burial service. I have been reading some of Lewis’s sermons lately, and I have been struck by the harmony of his voice with the voice of Charlotte Mason.

In a 1929 sermon, he spoke about one of my favorite chapters in the Bible: John 11. He reflected on the profound encounter of Martha and Mary with Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus, in light of their earlier encounter with Him in Luke 10. Lewis observes:

It was to Martha that Jesus said ‘I am the Resurrection and the Life’: the Martha who was cumbered with much serving: the Martha who was careful and troubled about many things, lest the careful housewife might fail in ministering to the comfort and honour of her Guest. Mary had been content to sit at His feet drinking in His words: to choose the good part that should not be taken from her. The silence of Jesus was enough for her. She could feel His unspoken sympathy. There was no need for her to speak either.

I believe Charlotte Mason saw in Mary of Bethany a pattern of faith and devotion. It is evident in her poem “The Good Part,” which you can read or listen to here. And it is evident that Miss Mason chose the good part too.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVI

In the introduction to her first poetry volume, Charlotte Mason explained her rationale. “Verse,” she explained, “offers a comparatively new medium in which to present the great theme. It is more impersonal, more condensed, and is capable of more reverent handling than is prose; and what Wordsworth calls ‘the authentic comment’ may be essayed in verse with more becoming diffidence.”

People often wonder what Charlotte Mason thought about prayer. There is a way to find out, and it is a way that is condensed and reverent. It is compact and beautiful. It is inspiring. It is a poem about the Lord’s Prayer. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVII

Charlotte Mason never hesitated to challenge the philosophers who denied the possibility of miracles. Again and again she insisted, not tentatively but with conviction, that miracles are essential to the Christian faith. Her arguments often culminated with the phenomenon of prayer. Personal dealings with God, she wrote, are “of the nature of a miracle.” Thus if God does not perform miracles, prayer “becomes blasphemous.”

Again and again I have read and discussed these words with others. And whenever we do our faith grows stronger. These are potent words for the mind which satisfy our reason.

But what about words which satisfy our heart? Mason’s faith in miracles was no mere rational faith. To feel this, however, we must read her poetry. Her poems on prayer are among her most powerful. Do you believe in miracles? Then join with Miss Mason and pray the “The importunate prayer.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVIII

When Jesus teaches about prayer, he asks us to think about our children: “And of which of you that is a father shall his son ask a loaf, and he give him a stone? or a fish, and he for a fish give him a serpent? Or if he shall ask an egg, will he give him a scorpion?”

Even as we are thinking about loaves, and fishes, and eggs, we read in the Gospel of Luke the surprising final sentence: “If ye then, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children, how much more shall your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to them that ask him?”

The Navarre Bible puts this into perspective: “The Holy Spirit is God’s best gift to us, the great promise Christ gives his disciples (cf. Jn 5:26), the divine fire which descends on the apostles at Pentecost, filling them with fortitude and freedom to proclaim Christ’s message (cf. Acts 2).”

And so St. Josemaría Escrivá proclaims, “Jesus has kept his promise. He has risen from the dead and, in union with the eternal Father, he sends us the Holy Spirit to sanctify us and to give us life.”

Charlotte Mason recognized the significance of this gift. In her poetic commentary on this passage from Luke she writes, “No good thing that a man requires but comes with Pentecostal fires.” Read or listen to Mason’s spiritual poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXIX

Charlotte Mason consistently and faithfully held to the mysteries of the historic Christian faith. In the second of the Anglican Articles of Religion, she read that in Christ, “two whole and perfect Natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one Person, never to be divided, whereof is one Christ, very God, and very Man.”

In keeping with this mystery, Mason often contemplated the divine nature of Christ as well as His human nature. Sometimes she considered both in the span of a single poem. In Mark 3:19b–20, we read that Jesus and His disciples “went into a house. Then the multitude came together again, so that they could not so much as eat bread.” According to Ralph Earle, the modern equivalent would be, “They didn’t even have a chance to grab a bite to eat.”

Could the “Source of all strength” need rest? Could a “a Man, exhausted, faint,” be “our God of mighty works”? And what did the crowds find when they came to that house in Capernaum?

The found one who was truly man, for sure. But Mason affirmed that they were also “to find the Very God!” Read or listen to Mason’s poem “He cometh into an house” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXX

The Old Testament closes with words that open the message of the New: “And he will turn the hearts of the fathers to the children.” It is a message that changed the course of my life, when I realized that when God gave me children, He also gave me a mission.

It is a message of love, reconciliation, and unity. What relationship can be more fruitful, more blessed, more promising, than that between parents and children?

It is this message that makes the pain of Mark 3:21 so acute: “And when his family heard it, they went out to seize [Jesus], for they were saying, ‘He is out of his mind.’” According to James R. Edwards, “the Greek wording is even more explicit: ‘they went to seize him, believing that Jesus had gone berserk.’”

It is a shocking statement, so starting that it does not even appear in the parallel passages in Matthew (12:22) and Luke (11:14). Edwards reminds us that it “is a calculated reminder that those closest to Jesus may indeed oppose him, and that proximity to Jesus—even blood relationship or being called by Jesus—is no substitute for allegiance to Jesus in faith and following.”

In Zechariah 13, the blessed prophet prophesies: “And one will say to him, ‘What are these wounds between your arms?’ Then he will answer, ‘Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.’”

Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s poem about the wounds that hurt the most, wounds at the hands of our friends. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXI

According to Lawrence R. Farley, “The title Beelzebul originally derived from the Hebrew baal zebul, ‘lord of the house,’ referring to the pagan god Baal. The title was later transformed into the derisive baal zebub, ‘lord of the flies,’ in 2 Kings 1:2, and at the time of Jesus it was used as a title for Satan.”

When Jesus cast out a demon, the Pharisees “did not deny that a demon had been cast out,” explained Farley, “but they attributed Jesus’ power to Satan.”

In her poem “One possessed with a devil,” Charlotte Mason captures the chaos and fear of the scene. Equally she captures the serenity when the Lord of all brought peace to a soul. Read or hear her poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXII

Chapter 49 of the great scroll of Isaiah is dedicated to the Servant of the Lord. At the end of the chapter we read:

Can plunder be taken from warriors, or captives be rescued from the fierce? But this is what the Lord says: “Yes, captives will be taken from warriors, and plunder retrieved from the fierce; I will contend with those who contend with you, and your children I will save.”

James R. Edwards explains that “the Servant’s mission is so seamlessly harmonious with God that God claims the Servant’s mission as his own, ‘I will contend … I will save.’”

The Servant came and did exactly what Isaiah said He would. He took plunder from warriors and captives from the fierce. But His detractors saw it differently. “By Beelzebul, the prince of demons, he is driving out demons,” they said.

Of course their logic made no sense. The strong man was bound because the King had arrived. Charlotte Mason delighted to elaborate the scene in a poem filled with imagery and life. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXIII

Years ago a friend of mine made a careful study of Charlotte Mason’s six poetry volumes. Along the way he kept a document entitled “Quotes from poetry” in which he added “fragments and complete poems with …comments … which may be relevant for my study.”

The document grew and grew until it came to 140 pages. And then he was kind enough to share it with me.

Towards the end, as he was going through volume 6, he copied the poem “He divideth his spoils” in its entirety. And then he included this note: “art should be freed from the devil’s spoils of men.”

I know why he wrote this and I know why he captured this poem. It is a remarkable example of how Charlotte Mason’s philosophy of education is inextricable from her theology, and even from her exegesis of Scripture.

How can art be freed from the devil? By taking away his armor. Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s stunning poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXIV

Charlotte Mason mentions “the unpardonable sin” three times in the Home Education Series. In all three instances she gives examples of people who have misunderstood this famous teaching from the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. But the words are there in the sacred text — so how are we to interpret it?

In her poem “The unpardonable sin,” Charlotte Mason turns from the negative to the positive and illuminates this difficult passage of Scripture for us. Her interpretation is brilliant and beautiful and draws the heart to love and not fear. Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s theologically rich and devotionally compelling poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXV

In her detailed account of the formation of habit in Home Education, Charlotte Mason warns of “The Dangerous Stage” (pp. 124–125). Just when it appears that a habit has been formed, the “critical moment” arrives. Sadly, that is when the mother relaxes her vigilance. The consequence is complete: “the mother’s mis-timed easiness has lost for her every foot of the ground she had gained.”

Ralph Earle finds in Matthew 12:43–45 a similar lesson about habit formation. He writes: “The warning for individuals is that reformation is not enough. One must not only cast off bad habits, but allow his heart to be filled with Jesus Christ and his life with worthwhile activity. Otherwise he will find himself a victim to worse habits than before. No heart can long stay empty. One’s only safety lies in keeping both heart and life filled with the good, that there may be no room for the bad.”

In that Gospel passage, Jesus warns: “When an unclean spirit goes out of a man, he goes through dry places, seeking rest, and finds none. Then he says, ‘I will return to my house from which I came.’” Norval Geldenhuys comments, “Even purely psychological considerations render it imperative that, when a person has passed through a crisis which has contributed to his renunciation of former sins and evil practices in his life, he must immediately in place thereof let his life be filled with what is beautiful and noble, otherwise the old sins and evils will return in renewed violence.… There cannot be a vacuum in man’s soul.”

Charlotte Mason’s poetic reflection on this important passage brings out the sober truth. One can be “made clean by Christ,” yet be “unplenished of His grace,” she warns. Read or hear the whole poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXVI

According to Robert Webber, the season we now call Advent was originally a period of penitential preparation for the baptismal service of Epiphany. It wasn’t until the sixth century that Advent evolved into a time of preparation for Christmas. “It must be noted, however,” says Webber, “that the shift from baptismal preparation to Nativity preparation did not diminish the penitential character of Advent.”

Today is the first day of Advent, and in many churches and homes, it remains a time not only of anticipation but also of repentance. I believe these two disciplines are essentially linked. Charlotte Mason’s beautiful poem “The empty house” illustrates that penance alone does not make for life. Penance alone just leads to an empty heart. To find life, the heart must be filled anew.

“Lord, take my vacant house and dwell therein, For only where Thou art’s no place for sin.” But how do we fill our hearts with Him? Not only our hearts, but the hearts of our children?

“Our fault, our exceeding great fault, is that we keep our own minds and the minds of our children shamefully underfed,” warned Charlotte Mason. Hearts are hungry. Let us dedicate this season of Advent to feeding these hearts on Christ. Read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXVII

In the Idyll Challenge for men we just finished Charlotte Mason’s first volume, Home Education. A thoughtful question was raised by a father in Brazil who asked about a sentence on page 319: “for though the will appears to be of purely spiritual nature, yet it behaves like any member of the body in this—that it becomes vigorous and capable in proportion as it is duly nourished and fitly employed.”

How, he asked, can we nourish the will of our children?

Several men, thoughtful readers of Miss Mason’s volumes, shared their perspectives. A consensus slowly emerged. If the will is of spiritual nature, then so must be its food.

Today’s poem by Charlotte Mason is timely for us. It corroborates our conclusion. Read or hear Mason’s poem about what “shall nourish thee and make thee grow.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXVIII

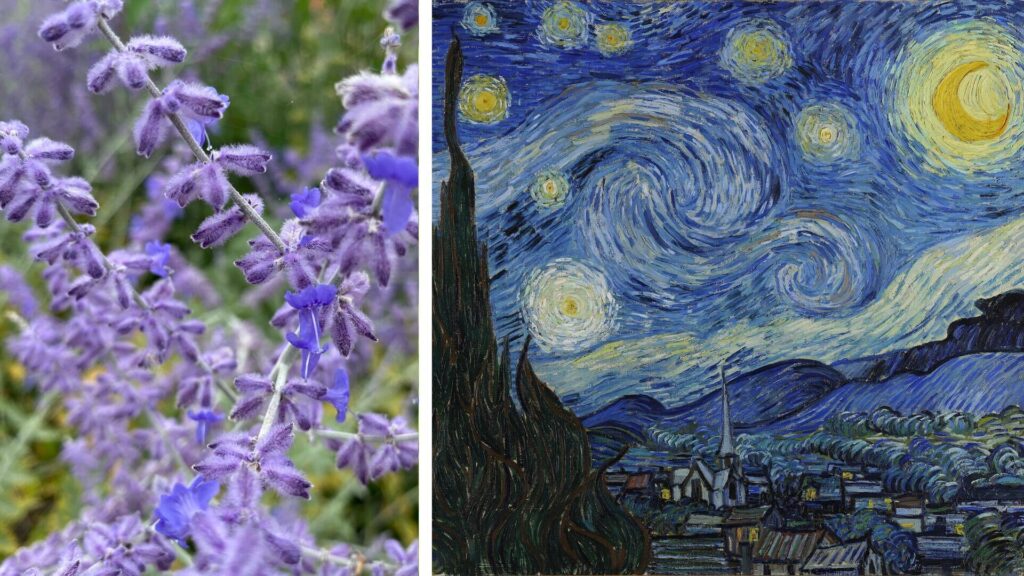

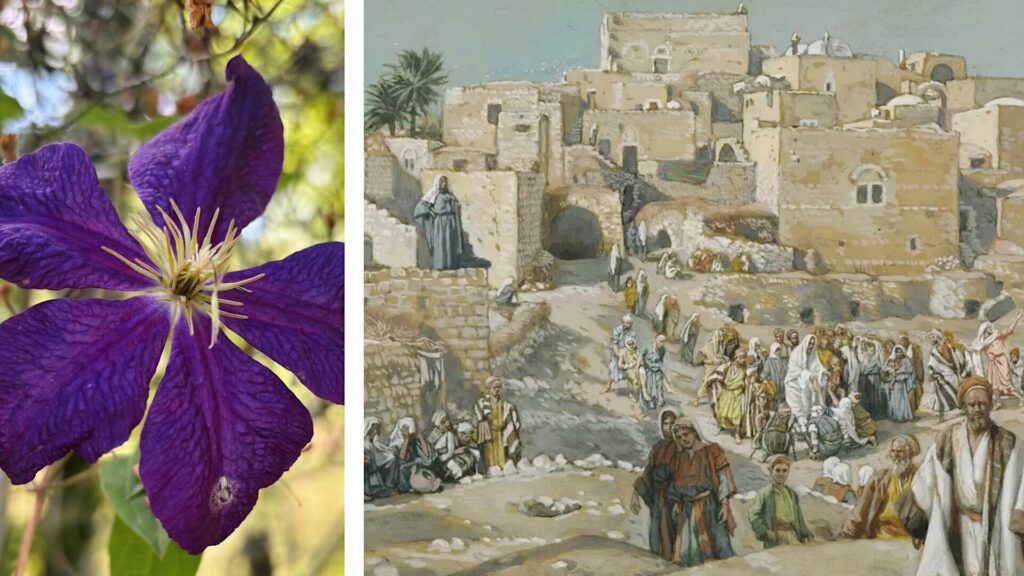

When Charlotte Mason assembled her volumes of original poetry, she always chose a dozen or so paintings by the great masters to illuminate certain poems and passages of Scripture. Many familiar artists were represented, including Titian, Rembrandt, and Dürer.

When she published her sixth volume of poetry in 1914, she may not have known that it would be her last. This volume included a print of her beloved Fortitude by Botticelli which she discussed at length in Ourselves. But when it came to the poem “The Sign of Jonah,” she chose something quite different.

Though in Home Education she recommended illustrations by “the Old Masters” to accompany Bible lessons, for this poem she selected a painting executed in 1894 — a mere 20 years before the publication of her work.

It is hard to fully grasp this when we normally think of Charlotte Mason as associated with old-fashioned things. How many devotees of the old masters today would choose a painting from 2004 to appear 80 pages away from a piece by Botticelli?

In 1904, G. K. Chesterton wrote an appreciation of artist G. F. Watts. He described Watts’s painting of Jonah as “frame-filling violence.” When Charlotte Mason wished to illustrate Christ’s proclamation that “a greater than Jonah is here,” she chose this piece by Watts instead of a work by any old master.

Perhaps it was the best painting available. Or perhaps it was a reminder by Miss Mason that the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure things new and old. Read or hear “The Sign of Jonah” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XXXIX

“Rabbi, to dine with me, wilt please?” asked the Pharisee. And Charlotte Mason imagined the enticements the man offered to Christ: a cool chamber, a cup of chosen wine, and some quiet talk. But allurements were unnecessary in this case, for Christ comes willingly to any who invite Him. Although when He arrives, what will He say?

In her poem “Woe unto you, Pharisees,” Charlotte Mason brings Luke 11:37–44 to life. The quiet talk ends in silence. Yes, Christ comes when He is invited, but He does not always say what His host wants to hear. Read or listen to Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XL

The richness of Bible lessons with Charlotte Mason’s The Saviour of the World poetry volumes eluded me until I read a Parents’ Review article by House of Education graduate Eleanor M. Frost. Then all the pieces fell into place. Writing in 1913, Miss Frost explained:

The New Testament work was the chronological study of part of Christ’s earthly Ministry, and this was taken from The Gospel History, with the corresponding notes from each Gospel in the ‘Commentary.’ For instance, suppose the lesson to be on the healing of Peter’s Wife’s Mother; the pupils would read the story in The Gospel History, then compare the accounts of this miracle in St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke, using the Notes in [J. R. Dummelow’s] The One Volume Commentary, next they would read the corresponding poem in Volume II. of The Saviour of the World. Studying the Gospel stories thus, the pupils get the four points of view about Our Lord and also the illustrative poems which help them to think and feel.

Thus a full lesson combines a “synthetic” study facilitated by The Gospel History and The Saviour of the World with an “analytic” study facilitated by the Dummelow commentary. It is a powerful learning experience.

Preparing such a lesson, however, takes time. It can be difficult to find the appropriate passages in the Dummelow commentary. So the Charlotte Mason Poetry team has decided to help. Starting today, our weekly poem from Miss Mason also includes the relevant commentary from Dummelow.

Now in one place you can find everything you need: the Gospel History reading, the commentary, the poem, and a beautiful audio recording of the poem. We hope it helps you unlock the depth of these Bible lessons with your children.

But here’s the biggest secret of all: it’s not just for your children. Why not begin your own personal study of the Gospels with Miss Mason? With insights from Dummelow, a synthetic and analytic study might just change your life. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLI

Laura Faunce graduated from the House of Education in 1899 before founding a PNEU school in 1906. “Trained by Miss Mason herself,” remembered Henrietta Franklin, “she made her principles her own and her lessons were delightful and appreciated by her pupils, as were the addresses which she gave from time to time to PNEU audiences.”

In 1923 Miss Faunce contributed to In Memoriam, the book written to celebrate Charlotte Mason’s legacy. Her essay was entitled “Miss Mason’s Ideal in School Life” and appeared on pages 165–173. She ended her piece with these words: “May I close with Miss Mason’s own words, which seem to set forth the creed of all her teaching: …”

Then followed Mason’s poem entitled “The Keys of Knowledge.” Would you like to read or hear the poem that sets forth the creed of Mason’s teaching? You can find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLII

Luke 11 ends with three verses unique to Luke. “In this paragraph,” writes Ralph Earle, “we see the animosity of the Pharisees at its unreasonable worst. As Jesus left the house, the scribes and the Pharisees began to harass Him, trying to provoke Him to say something for which they could get Him into trouble. They were lying in wait for Him, to catch something out of his mouth… The verb catch means literally ‘to hunt.’”

But as Charlotte Mason observed, Jesus was not afraid of this hunt. Whether in a storm of wind and rain, or a storm of angry men, Christ would go “His way majestic through.” Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s portrayal of Christ’s serenity in the face of trouble here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIII

Charlotte Mason sheds unusual light on the topic of hypocrisy. In her 1898 meditation entitled “Simplicity,” she asserts that we now have a superficial view of this vice. “Our rude modern notion of hypocrisy makes it the sin most easily to be avoided,” she explains.

The hypocrite, in our view, is the man who makes believe in the eyes of others to be that what he is not; but our Lord flashes a searching light upon his friends and upon his enemies and shews in a way never to be forgotten that the leaven to beware of is the posing before the eyes of our own consciousness, making believe to ourselves to be that which we are not. The all-penetrating leaven is that which we call insincerity; insincerity as to what we are, what we think, what we purpose, which is, alas, “the natural fault and corruption of the nature of every man,” unless as he is illuminated by the Light of the world.

One of the places Christ speaks of this “all-penetrating leaven” is Luke 12:1. A few years after writing her “Simplicity” meditation, Miss Mason wrote a poem about this passage in Luke. Not surprisingly, it develops and extends the theme with piercing and poetic power. Do we think we are free from hypocrisy? Let’s read or hear Charlotte Mason’s penetrating poem and ask ourselves again. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIV

Last week we shared Charlotte Mason’s poem about Luke 12:1–4 and noted that she had previously written about that passage in her 1898 meditation entitled “Simplicity.” In the Gospel of Luke, the subsequent passage speaks of the unforgivable sin (verse 10). Charlotte Mason also examined this in her piece on “Simplicity”:

If we consider that our Lord’s discourse is not a series of disconnected utterances, but a closely reasoned-out and amply illustrated argument, based upon the thesis, “When thine eye is single, thy whole body also is full of light,” we are better able to follow the thought in this most anxious passage.

Today we share Charlotte Mason’s poem about Luke 12:5–12 in which she examines “this most anxious passage” once again. You can read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLV

In Numbers 27 the daughters of Zelophehad came to Moses crying out for justice. “Our father died in the wilderness,” they pleaded; “Why should the name of our father be removed from among his family because he had no son? Give us a possession among our father’s brothers.”

Moses brought their case before the Lord and then gave them an inheritance.

Centuries later in a situation recorded only by Luke, a man came to Jesus crying out for justice. “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.”

Jesus’ response was dramatically different from that of Moses. “Jesus rejected the role of judge or divider of inheritances, even though Moses had handled a similar request” explains R. Alan Culpepper. “Jesus rejects the man’s request because he will not participate in satisfying the greed that he senses had prompted it. Instead of helping the man to get his inheritance, he points the man to a different understanding of life. Life is not to be valued or measured in terms of wealth or possessions. One may gain the whole world and lose one’s soul… On the other hand, true blessing comes to those who hear the Word of God and do it.”

Charlotte Mason brings the scene to life in her poem on this passage. Read or hear it here, along with commentary by J. R. Dummelow.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVI

One of the most profound poems by Charlotte Mason is called “Of the single eye.” It is based on a verse from Matthew that is difficult to interpret: “The lamp of the body is the eye. If therefore your eye is good, your whole body will be full of light” (6:22).

Years ago Nancy Kelly helped me understand Mason’s interpretation of that verse. In “Of the single eye,” Mason suggests that the eye really is a lamp that illuminates what we choose look at. “The things so dazzled thee, ’twas not their light, But an illusive brilliance cast by thee;” writes Mason.

The idea is that things are only as valuable or as desirable as we ourselves make them. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus says, “Take heed and beware of covetousness, for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of the things he possesses” (12:15). When Mason writes on that verse, it is not surprising that she returns to her theme. “Your mind makes its own values,” she warns.

Read or listen to Mason’s poem entitled “Possessions,” which is in many respects a sequel to “Of the single eye.” The poem offers solemn reflection for you and those in your care. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVII

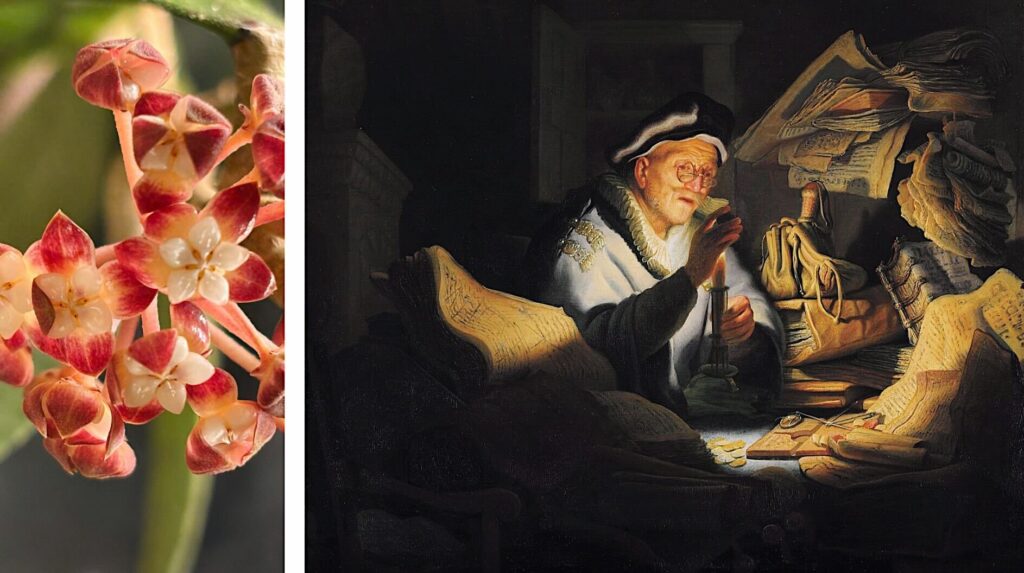

“Do not be afraid when one becomes rich,” writes the Psalmist, “for when he dies he shall carry nothing away; his glory shall not descend after him. Though while he lives he blesses himself (for men will praise you when you do well for yourself), he shall go to the generation of his fathers; they shall never see light.”

In Luke 12, Jesus told the parable of a man who blessed himself because he had become rich. In six concise verses Christ left us with a clear message and a space for our imagination. Charlotte Mason filled that space with her expansive poem “The rich fool.” You can read or hear that poem here and immerse yourself in the thought of being rich with God.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVIII

“The Hebrew was stirred by what he saw to thoughts of God,” proclaimed Rev. Francis Lewis at St. Mary’s in Ambleside in 1926. “Everything was fraught with the deepest lessons of spiritual truth to the one whose heart was attuned to God. Our Lord drew some of His greatest lessons from the birds and from the lilies of the field. In their lives was revealed the watchful and loving providence of a heavenly Father.”

A unique verse in the Gospel of Luke reveals that our Lord drew a lesson even from the raven. So did Miss Mason. Read or hear her poem “Be not anxious”, along with commentary by J. R. Dummelow here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIX

When William Holman Hunt painted his The Light of the World in 1851, the door that he featured had an unusual trait: there was no handle. It could only be opened from inside.

“What easier than let in, I pray, The lord of th’ house without delay?” asks Charlotte Mason in her poem “The watchful servants.” As in Hunt’s famous painting, the master is returning at night. All the servants need to do is open the door.

But there is a problem, and Mason captures the moment powerfully in her verse. And then the outcome is wonderful, marvelous, and moving. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem L

“Sadly,” warns Pastor Shane Idleman, “many confuse God’s patience with His approval.” Charlotte Mason saw a similar tendency: Christ’s servants sometimes “mistake needful delays for His forgetfulness.” But warnings like this are easier to remember when “clothed in a tale,” so Christ gives us a parable.

Mason’s poem “The thief in the night” takes this the one-sentence parable and expands it to a story. The poem draws us in so we can linger on the important and urgent warning of the tale. Read or hear the poem, along with notes from J. R. Dummelow, here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LI

“We have all wondered,” wrote Charlotte Mason, “that Christ should expose the profoundest philosophy to the multitude, the ‘Many,’ whom even Socrates contemns” (vol. 6 p. 332). Apparently this wonder extends all the way back to the earliest days of Christ’s ministry. “Lord, do You speak this parable only to us, or to all people?” asks St. Peter in Luke 12:41.

Charlotte Mason begins to unfold this theme in her poem “Lord, is this word for us?” Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LII

“Who then is that faithful and wise steward,” asks Jesus in Luke 12:42. “Blessed is that servant whom his master will find so doing when he comes. Truly, I say to you that he will make him ruler over all that he has.”

It is a parable, of course, so we must interpret what it means. What is this reward that is offered, to be “ruler over all that he has”?

Charlotte Mason does not hesitate to put forward her own interpretation. In her poem “The faithful steward” she envisions a reward in harmony with her values. Read or her Mason’s poem and discover what faithful stewardship she has in view. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LIII

In 1912, Charlotte Mason wrote a series of letters to the Times which were published the following year with the title The Basis of National Strength. The first letter focused on knowledge. “It is for their own sakes that children should get knowledge,” she wrote.

Each letter appeared as a crescendo, strengthening and echoing her theme. And then finally in the fourth letter she made her great claim: “knowledge is the basis of a nation’s strength.”

Reading this booklet, now forever made part of her final book, one might think that for Mason, knowledge is the highest good. But it is in her poetry that we find the completeness of her thought.

A day is coming, she foresaw, when a Judge is coming. And then we will be asked not “What did you know?” but “What did you do with what you know?” Read Mason’s important and challenging poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: Behold the Bridegroom Cometh by William Blake Richmond

Book IV Poem LIV

In Charlotte Mason’s poem, she describes how the disciples saw, “upon the Master’s countenance, a change.” Gone was “the aspect sweet they knew”; in its place “a prophet’s gaze, far-seeing, pained, constrained.”

What follows in the poem is a change in Mason’s countenance as well. She takes us to the heart of Christ’s words of fire and we feel the heat.

J. R. Dummelow said of Luke 12:49 that “The Prince of Peace comes to bring strife and bloodshed, fire and sword, into the world, because only through war can lasting peace be attained. Some, however, understand by fire, the fire of Christian love.”

Is it the fire of judgment or the fire of love? Or are the two linked in some paradoxical way? Read or listen to Charlotte Mason’s poem and enter the mystery. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

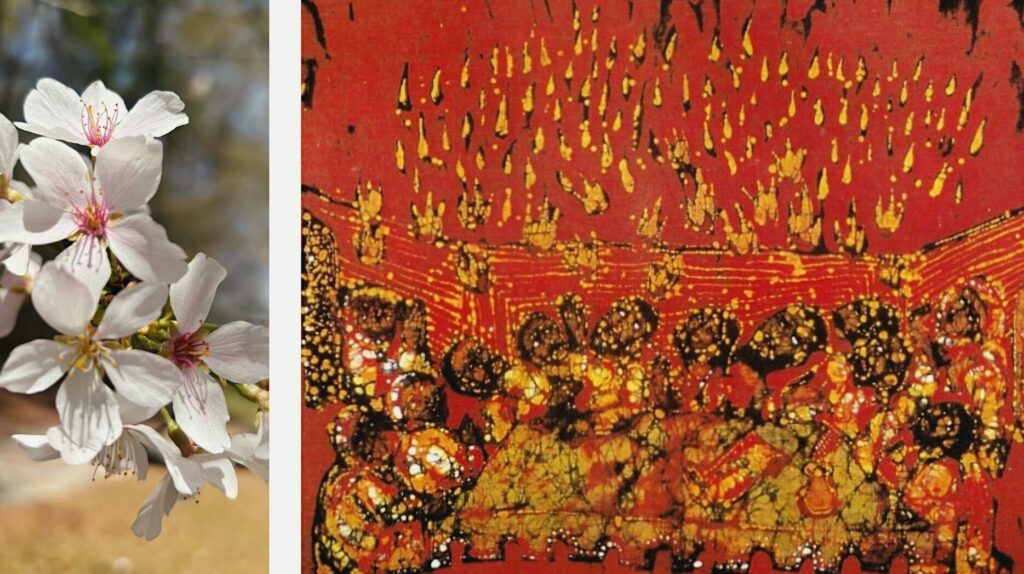

🖼️: Pentecost by P. Solomon Raj

Book IV Poem LV

Johannes Vermeer’s 1668 oil on canvas The Astronomer resides today in the Louvre in Paris. Arthur Wheelock says of it and its companion piece: “One senses in the scholars’ purposeful expression as they lean forward, with one hand firmly grasping a solid support, the excitement of intellectual inquiry as their inquisitive minds actively search for answers to questions they have posed about the earth and the stars.”

It’s a wonderful picture of the thirst for knowledge which compels people to “discern the face of the sky and of the earth.” But does that thirst also extend to discerning the face of God? It’s the question Christ asks in Luke 12:57, paraphrased by J. R. Dummelow as, “Why, even without signs, do you not judge rightly of Me and My doctrine by the natural light of reason and conscience?”

Charlotte Mason’s poem “Weather Signs” helps us meditate on these verses, and encourage us to actively search not just the heavens, but the words of the One who made them. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LVI

The Book of Common Prayer provides this Collect, or prayer of invocation, for Easter Sunday:

Almighty God, who through thine only-begotten Son Jesus Christ hast overcome death, and opened unto us the gate of everlasting life; We humbly beseech thee that, as by thy special grace preventing us thou dost put into our minds good desires, so by thy continual help we may bring the same to good effect; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost ever, one God, world without end.

In 1921 Charlotte Mason commented on this prayer:

What a grand opening to the Collect for Easter Day!—“opened the gate of everlasting life.” We rather expect after going through all the hopes of Easter to pass on to something large and great and wonderful, and we find a prayer that any one can use at any time—“Put into our minds good desires.”

This is indeed a prayer that anyone can use at any time — a prayer that God would enable us to desire the good and shun the evil. It is a prayer involved with repentance, which is the theme of the poem we share today from her sixth volume of poetry. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: Pilate Washing His Hands by Mattia Preti

Book IV Poem LVII

“Now let me sing to my Well-beloved

A song of my Beloved regarding His vineyard.”

So opens the fifth chapter of Isaiah. “The readers of this book can easily work out what this vineyard stands for,” explains John Goldingay. However, “for the original audience of Isaiah’s song, matters were more complicated… Isaiah appears before his audience as a minstrel singing a love song on behalf of his best friend, perhaps as his best man. It appears at first to be a touching song about the man’s efforts to cultivate a fruitful relationship or a fruitful marriage, yet worryingly its lines have the short second half characteristic of the limping lament form, which suggests that it will turn out to be a sad song.”

In Luke 13:6, Jesus begins a parable with these words: “A certain man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard.” Would his hearers have immediately thought of Isaiah’s song to his Well-beloved? But then what is a fig tree doing in a vineyard?

In Charlotte Mason’s imaginative poem “The barren fig-tree,” she enters the mindset of Christ’s first-century hearers. In verses that pose more questions than answers, she leaves us again wondering if it will turn out to be a sad song. Read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

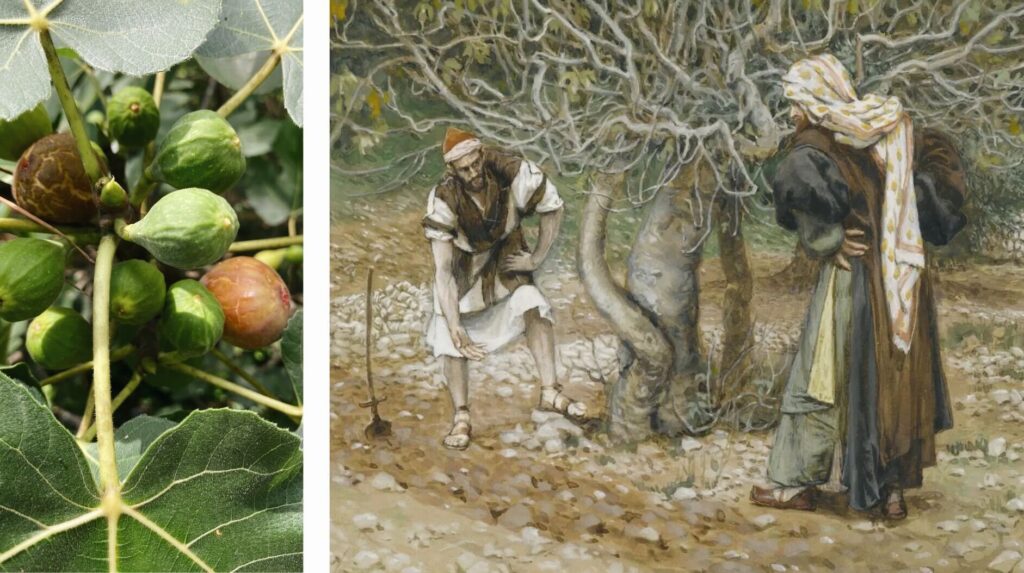

🖼️: The Vine Dresser and the Fig Tree by James Tissot

Book IV Poem LVIII

“Imagine that you are on the edge of the crowd that has followed Jesus so far,” suggests N. T. Wright. “You haven’t heard everything and haven’t understood all you’ve heard, but you think you’ve got the general drift of it all and find it both compelling and alarming. In you go with Jesus to the synagogue on this sabbath. What do you see, and what sense does it make to you?”

“You see—everybody sees—this poor woman. She was probably a well-known local character. In a village where everyone’s life was public, people would know who she was and how long she’d been like this. Luke says she had ‘a spirit of weakness’, which probably means simply that nobody could explain medically why she had become bent double. Some today think that her disability had psychological causes; some people probably thought so then as well, though they might have said it differently. Maybe somebody had persistently abused her, verbally or physically, when she was smaller, until her twisted-up emotions communicated themselves to her body, and she found she couldn’t get straight. Even after all the medical advances of the last few hundred years, we are very much aware that such things happen without any other apparent cause.”

More than one hundred years ago, Charlotte Mason imagined it too. She imagined what she would have seen, heard, and felt. And she imagined what would happen when, in the words of Stephanie Buckhanon Crowder, “Jesus restore[d] [the woman’s] humanity by calling her to him and by touching her, thereby symbolically drawing an ‘untouchable’ once again into community.”

Let Charlotte Mason draw you into the scene in her unforgettable poem “A spirit of infirmity.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

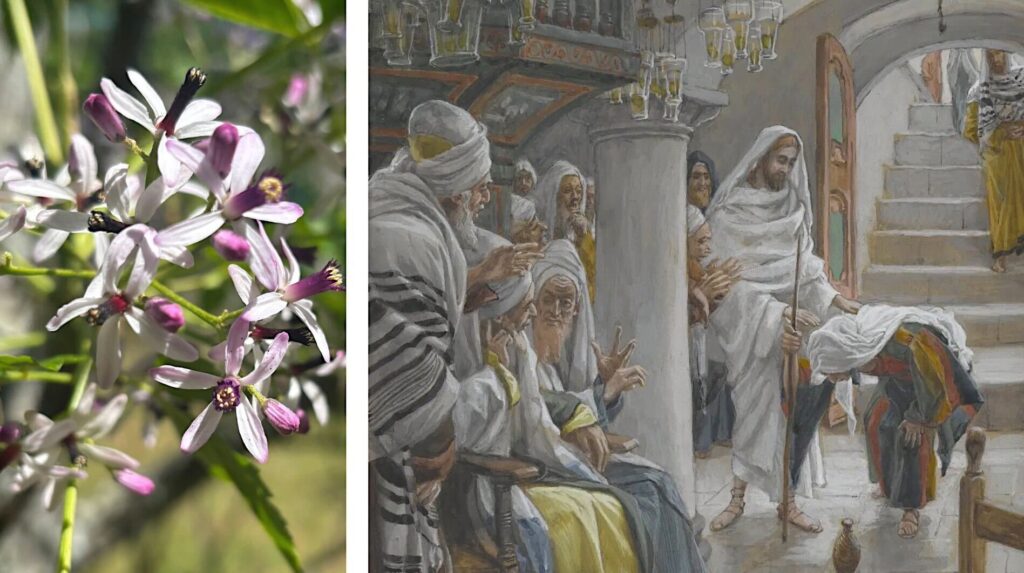

🖼️: The Woman with an Infirmity of Eighteen Years by James Tissot

Book IV Poem LIX

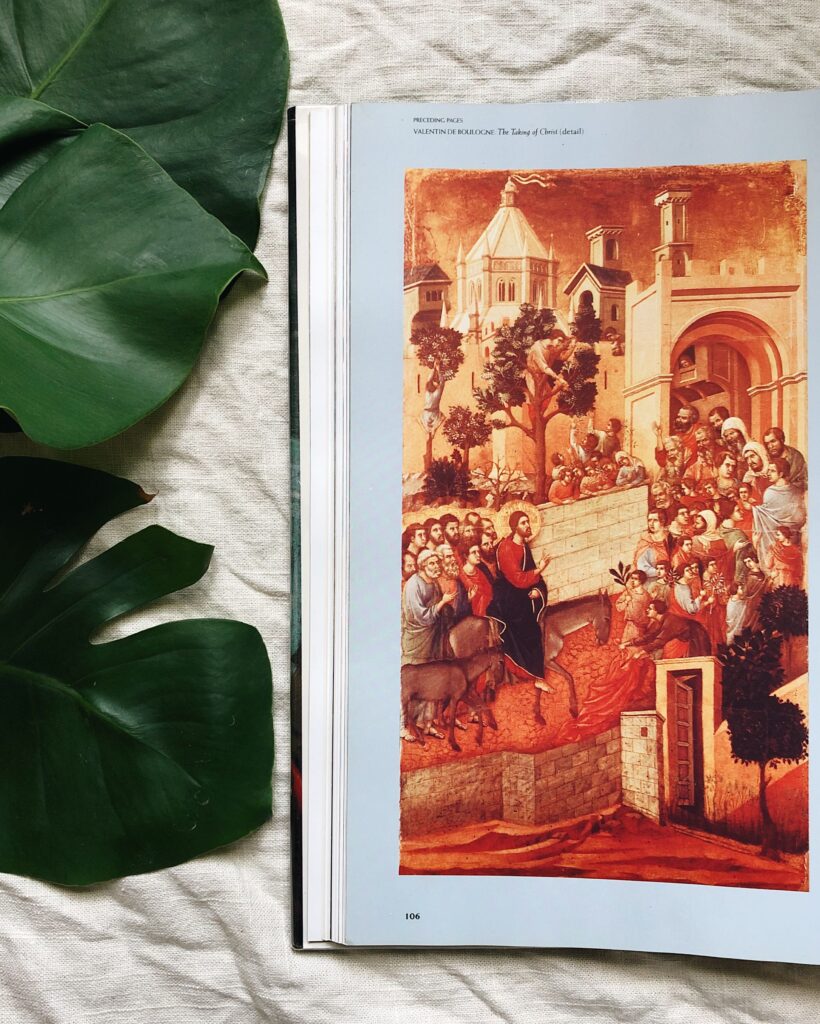

My son and I have been on a multi-year journey through Charlotte Mason’s The Saviour of the World, and we are currently on volume 6. This volume covers an extended portion of the Gospel of Luke that contains material not found in any other Gospel. It has been an eye-opening study for me.

Luke seems to delight in recording details about our Lord’s final journey to Jerusalem. Reading Luke’s gospel in the light of the Gospel History has helped me appreciate these passages in a whole different light. It evidently captured Charlotte Mason’s imagination as well.

In Luke 13:22 we read, “And He went through the cities and villages, teaching, and journeying toward Jerusalem.” Miss Mason lingered on this thought of Jesus and His journey to the momentous events soon to follow. Her poem about this verse brings us into the moment, and invites us to reflect more deeply on our Lord and His Word. Read or hear her poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: He Went Through the Villages on the Way to Jerusalem by James Tissot

Book IV Poem LX

“Although it is a blessed thing to be a Christian, it is not easy,” writes J. R. Dummelow. “The Christian journeys along the narrow way of self-denial discipline and mortification, perhaps of contempt and persecution, but the end of it is life.”

These words would have been read by Charlotte Mason’s students, according to her own account on p. 164 of An Essay Towards a Philosophy of Education: “When pupils are of an age to be in Forms V and VI (from 15 to 18) we find that Dummelow’s One Volume Bible Commentary is of great service… I need only say we find it of very great practical value.”

Writing in 1913, House of Education student Eleanor M. Frost concisely described a lesson as follows:

… the pupils would read the story in The Gospel History, then compare the accounts of this miracle in St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke, using the Notes in [Dummelow’s] The One Volume Commentary, next they would read the corresponding poem in Volume II. of The Saviour of the World.

Each week the Charlotte Mason Poetry team gathers these materials together to facilitate the exact kind of study Miss Frost describes. Today’s poem is about the narrow way. Find the story in The Gospel History, the commentary from Dummelow, and the poem by Miss Mason all in one place — including a recording of the poem by @antonella.f.greco. It’s at this link.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: To Pass Through The Narrow Gate by Jan Luyken

Book IV Poem LXI

The Revised Common Lectionary reading for the second Sunday of Lent is Luke 13:31-35. In these verses we read of the threats of Herod Antipas and how our Lord responds. Christ shows His perfect security in His Father’s timing; He shows that now is the time for healing and curing, not for hiding and dying. With a beautiful image from nature, Mason connects the theme of this passage to end Christ has in view. What happens on the third day? I invite you to read and meditate on Charlotte Mason’s poem, which speaks to security in the present, and hope for Easter Day. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LXII

St. Augustine wrote, “You see, brethren, how a hen becomes weak with her chickens. No other bird, when it is a mother, shows its maternity so clearly. We see all kinds of sparrows building their nests before our eyes; we see swallows, storks, doves, every day building their nests; but we do not know them to be parents, except when we see them on their nests. But the hen is so enfeebled over her brood that even if the chickens are not following her, even if you do not see the young ones, you still know her at once to be a mother. With her wings drooping, her feathers ruffled, her note hoarse, in all her limbs she becomes so sunken and abject, that, as I have said, even though you cannot see her young, you can see she is a mother. That is the way Jesus feels.”

That is the way Jesus feels. He felt that way two thousand years ago when He entered Jerusalem, and He feels that way today. He has room for you under His wings. Won’t you go and find your home there?

Meditate on the heart of Christ with Charlotte Mason’s poem today, which you can read or hear at this link.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LXIII

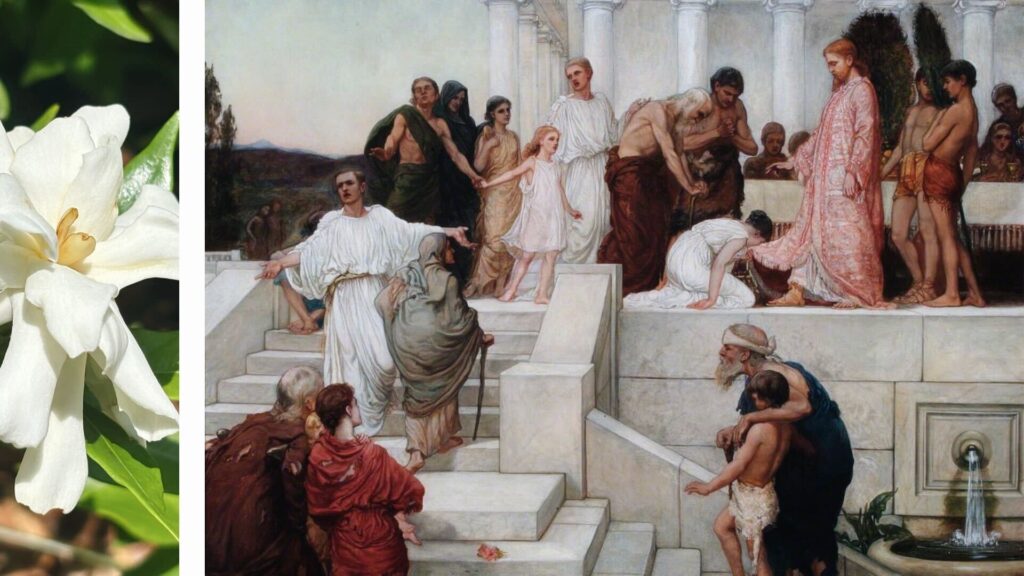

Fritz von Uhde was a German painter who lived from 1848 to 1911. He lived during the time when impressionists were changing the world of art, and he shared in certain aspects of the movement. What is most striking about his art to me, however, is not so much that he painted out of doors or that he experimented with color, but that he portrayed Christ with us.

For example in his 1885 painting Grace, a “lower class family … in the midst of praying, ‘Come, dear Jesus, be our guest’, are greeted by the appearance of Jesus in their humble parlor.” Similarly, in his The Sermon on the Mount, Christ addresses a crowd of 19th century harvesters. My favorite is his Suffer Little Children to Come Unto Me.”

Charlotte Mason read in the Gospel of Luke how Jesus lamented over Jerusalem. Her poetic art then followed a similar path to the visual art of Fritz von Uhde. Mason imagined what would happen if Jesus visited “our city.” Would He admire all the churches and beautiful things, or grieve for the neglected poor? Read or hear Mason’s challenging and touching poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: Suffer the Little Children to Come Unto Me by Fritz von Uhde

Book IV Poem LXIV

Luke chapter 14 opens with a meal setting, which continues until verse 24, according to D. L. Bock. “But this is not an ordinary dinner party, nor is the conversation normal table talk. On the menu is theological and ideological reflection about what God is doing.”

The scene opens with an unexpected guest. “At the meal is a man with dropsy,” explains Bock, “which means his limbs are swollen with excess body fluids—a condition much discussed in later Judaism and associated with uncleanness and immorality… Jesus does not shy away from the situation.”

Charlotte Mason’s poem “Dinner on Sabbath” captures the theology — and the emotion — on the menu at this meal. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: Christ Healing the Dropsical Man, Monastery Dečani fresco

Book IV Poem LXV

The dinner of Luke 14 continues with a parable from Christ. D. L. Bock observes that “Jesus’ point is not that we should connive to receive greater honor. Rather, he is saying that honor is not to be seized; it is awarded. Jesus is not against giving honor to one who deserves it, but he is against the use of power and prestige for self-aggrandizement. God honors the humble, and the highway of humility leads to the gate of heaven.”

Charlotte Mason develops this theme in her poem “The Judge in presence.” “God retains His high command,” she declares. Read or hear the complete thought here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LXVI

The dinner of Luke 14 continues with a second parable from Christ. “The parable of the supper, which follows, is a parable all right,” explains N. T. Wright, “but Jesus really seems to have intended his hearers to take literally his radical suggestion about who to invite to dinner parties.

“Social conditions have changed, of course, and in many parts of the world, where people no longer live in small villages in which everyone knows everyone else’s business, where meals are eaten with the doors open and people wander to and fro at will (see 7:36–50), it may seem harder to put it into practice. Many Christians would have to try quite hard to find poor and disabled people to invite to a party—though I know some who do just that. Nobody can use the difference in circumstances as an excuse for ignoring the sharp edge of Jesus’ demand.”

Apparently Charlotte Mason did not want to ignore the sharp edge in her poem about this parable. Read or hear “The host reproved” by Charlotte Mason here.

@artmiddlekauff

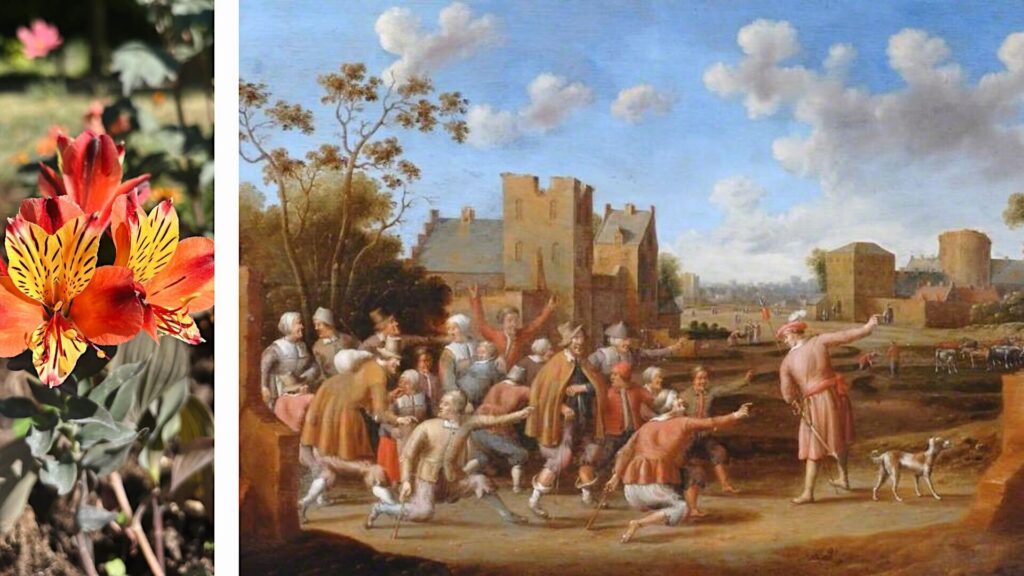

🖼️: Parable of the Great Banquet by Brunswick Monogrammist

Book IV Poem LXVII

The meal setting of Luke chapter 14 concludes with verses 15–24. As D. L. Bock explains, “this is not an ordinary dinner party, nor is the conversation normal table talk. On the menu is theological and ideological reflection about what God is doing.” The final parable is no exception.

In Charlotte Mason’s poem, she observes that at this meal, “all Christ’s words were wholly lost,” for “one turned to Him with grave accost.” He called out, “Blessed is he who shall eat bread in the kingdom of God!”

On the surface of it, Christ’s response seems to surrender a straightforward interpretation. But N. T. Wright encourages us to dig deeper. “Christians, reading this anywhere in the world, must work out in their own churches and families what it would mean to celebrate God’s kingdom so that the people at the bottom of the pile, at the end of the line, would find it to be good news. It isn’t enough to say that we ourselves are the people dragged in from the country lanes, to our surprise, to enjoy God’s party. That may be true; but party guests are then expected to become party hosts in their turn.”

Follow this link to read or hear Charlotte Mason’s poetic reflection on this chapter.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: The Parable of the Great Supper by Theresa Thornycroft

Book IV Poem LXVIII

In the parable of the great supper, the people who are invited refuse to come. The excuses, explains J. R. Dummelow, “show careless unconcern, not hardened wickedness. Business occupations, family ties, and various distractions, are pleaded as excuses for not taking God’s summons seriously.”

It is just such careless unconcern that Charlotte Mason feared she might find in her own heart. So she wrote out a beautiful poetic prayer in response to this parable. Read and pray with her that we too may be protected from our own trivial cares. The poem is here.

@artmiddlekauff

🖼️: The Parable of the Great Supper by Cornelis Droochsloot