Reverence for the Work of the Holy Spirit in Children

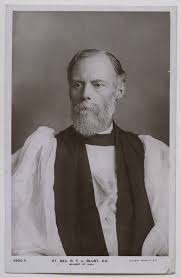

By The Ven. Archdeacon Blunt, D.D.

Vicar of Scarborough, &c.

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the opening pages of the December, 1890 issue of The Parents’ Review, in the first year of the magazine’s existence. Written by Richard Frederick Lefevre Blunt, the article was first read by him as a paper before the Church Congress on October 3, 1890. Blunt cites Mason’s Home Education, published four years before, as one of his sources. We shall see, however, that Blunt draws more phrases and ideas from Mason than he cites. The paper is significant in that a senior church official (an archdeacon) is citing Charlotte Mason before a major ecclesiastical assembly. It points to the fundamentally theological nature of Mason’s educational philosophy. It also shows how a contemporary theologian reflected upon Mason’s ideas that were later to be specified as the first, second, and twentieth principles in her synopsis.

Brackets with normal text represent footnotes in the original. Brackets with gray text represent footnotes added by the Charlotte Mason Poetry editor. Special thanks to the volunteer typists who have made this transcription available for study by the general public.

It was a noble utterance of the Roman satirist [Juvenal]—“Maxima debetur puero reverentia.” “The deepest reverence is due to a child.” It was a true application of that reverence when he bade the parent restrain himself lest his child should suffer from his evil example. We Christians cannot see less to reverence in our children than Juvenal saw; the reverence we would pay is in full view of the revelation, both of God’s holiness and of man’s fall; for the cardinal doctrine of the Christian Church is not human corruption, but human redemption; not the Fall, but the Incarnation; not the omnipotence of Satan, but the universal fatherhood of God; and the application of this doctrine is found for us Churchmen in the unequivocal assertion of the Church Catechism, which teaches each baptized child, however ignorant, however thoughtless, however sinful, to acknowledge that he is “a member of Christ, the child of God, and an inheritor of the kingdom of heaven” [Anglican Book of Common Prayer]. I take it therefore that the reverence due to Christian childhood is the expression of faith in the covenant relation of each child to Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. On the face of each little one we may trace some ray of “the light coming into the world, which lighteth every man” [John 1:9], some likeness to the King who says not less of children in English nurseries than of those in Gallilean homes:—“Of such is the kingdom of heaven” [Matthew 19:14].

To suggest some thoughts concerning this reverence for the Holy Spirit in our children, especially in little children, and some ways of showing it in our treatment of them, is the object of this paper.

It has been lately said that “the child as an object of public solicitude, and of social obligation the most sacred, is entirely a modern discovery.” There is a good deal of truth in that statement; for although potentially this solicitude for children was contained in Christ’s treatment of them and commands concerning them, practically it has taken centuries to arouse the conscience of Christendom to the duty of copying His example and of doing His behest. True, the doctrine of the Incarnation involved the sacredness of childhood; the life of the child Jesus hallowed all child-life; Christian art in its devotional representations of the Divine Child in His mother’s arms enshrined it; but even chivalry failed to secure for childhood any share of the glory with which it surrounded womanhood. Long centuries ago Christ “set the child in the midst” [Matthew 18:2] and there the Christian Church ought always to have beheld it. But at last we are beginning to understand His Divine purpose, and are learning to minister to each side of child life.

[Editor’s note: In the preceding paragraph, Blunt alleges that since its inception, Christendom has failed to understand Christ’s teachings about the nature of the child. He claims that it is only in his day that the conscience of Christendom was awakening. Charlotte Mason shared this view that her first principle (“Children are born persons”) was revolutionary.]

Infant mortality now so appalling must be no longer tolerated; cruelty to children must be punished as specially heinous; child labour must be still further restricted. Children’s health, happiness, instruction, education, and recreation are being cared for. Children’s hospitals, orphanages, homes, reformatories, industrial schools are multiplying daily. The provision of science, art, poetry, music, country holidays is employing the thoughts and exercising the ingenuity of thousands; Sunday schools, children’s services, missions, and guilds are of the deepest solicitude to the Church; and parents’ unions, children’s help societies, parents’ educational unions are all part of the machinery by which we may be helped to help them. The child question is one of the great questions of our time. The Church, the State and public opinion are all agreed in recognising the paramount importance of the child set in our midst as the hope of the coming generation. Now, if all this be true, it is reasonable to inquire how this responsibility is being exercised. It may be, new perils will beset the child of to-day not less dangerous than those that beset its forefathers. It is tolerably certain not to be neglected, but it may be spoiled, it may be artificially developed, it may become the subject of experiments that may

Substitute an universe of death

For that which moves with light and life informed,

Actual, divine and true. [The Prelude, Wordsworth]

[Editor’s note: Mason draws extensively from this autographical poem by Wordsworth in chapters 17 and 18 of School Education.]

In our very eagerness we may do too much, where before we did too little, or we may begin at the wrong end, and wholly engrossed in our own work for the child we may forget God’s.

There are two methods of training children in the things of God, two lines of thought to support these methods, perhaps two classes of Christians who sympathize exclusively with one or the other. Each represents one side of truth; our danger is lest we exaggerate the one and pass by the other. There is the tendency in some minds to overrate the effects of the Fall, in others to overlook the Fall in the Redemption. Some teachers ignore altogether the intuitive impulses of the child towards good; others exaggerate them. Some would “esteem it the height of enthusiasm to look for any religion except as the result of direct teaching,” others would trust entirely to what has been called “the devout intuition of the human mind,” and would only preserve the child from moral taint. The one class read the Lord’s command as if he said, “Make little children like yourselves,” forgetting that he really said, “Become yourselves like little children” [Matthew 18:3]; while the other would forget that we are bidden to “train up a child in the way he should go” [Proverbs 22:6], and the principle which underlies it, that Divine grace is no substitute for human action. The representative of the former is to be found in Locke, of the latter in Wordsworth. In a word, the one class believe exclusively in tuition, the other in intuition.

[Editor’s note: This preceding paragraph closely parallels Mason’s thought in Chapter 3 of Towards a Philosophy of Education, which is her exposition of her second principle: “[Children] are not born either good or bad, but with possibilities for good and for evil.”]

Now the course of wisdom lies here, as elsewhere, not in a safe via media, but in due recognition of both truths. If “grace is not tied to means,” God’s work cannot be limited by ours. With our aid, or without our aid, He is always seeking to form in each of His children His Divine image. It is His work apart from us that we are to further, as well as His work through us which we are to accomplish. In fact, we are not to treat a child as if he were a block of marble which we are to hew into a statue, but as a plant of God’s planting which we are to nourish and develop.

[Editor’s note: Here Blunt again affirms Mason’s view of the personhood of the child. Mason expresses a similar sentiment when she quotes Pastor Pastorum by H. Latham on page 183 of School Education:

“Our Lord,” says this author, “reverenced whatever the learner had in him of his own, and was tender in fostering this native growth—… Men, in His eyes, were not mere clay in the hands of the potter, matter to be moulded to shape. They were organic beings, each growing from within, with a life of his own—a personal life which was exceedingly precious in His and His Father’s eyes—and He would foster this growth so that it might take after the highest type.”]

So He bids us work and bids us pray, filled with reverence for Him and love for His little ones.

… When will their presumption learn,

In the unreasoning progress of the world

A wiser Spirit is at work for us,

A better eye than theirs, most prodigal

Of blessings, and most studious of our good,

Even in what seem our most unfruitful hours. [The Prelude, Wordsworth]

[Editor’s note: Mason later quoted the above lines of Wordsworth in her 1914 Parents’ Review article entitled “Trop de Zèle.”]

Let us then listen to the words of Christ regarding them:—and first, His prohibitions—“Despise not, offend not, hinder not, one of these little ones.”

[Editor’s note: In the above sentence, Blunt (writing in 1890) follows Mason’s 1886 formulation of the “code of education in the Gospels” (Home Education, p. 12). Although Blunt does not note his dependence on Mason here, he cites her in a later paragraph.]

“Despise not.”—We despise Christ’s little ones when we neglect them. The parent who delegates to nurse or teacher their earliest training in the things of God despises them. The father who leaves all the religious teaching of his boys to their mother despises them.

[Editor’s note: Blunt admonishes the parent who neglects his duty by delegating to nurse or spouse.]

Oh, how painfully common amongst all classes is this neglect! No wonder, as the boys become men, they hand on the evil tradition that religion is for women and children, since for their religion their father cared nothing. If in the very earliest years the mother is the best teacher, the godly father will soon be at her side and do his part. The neglect of fathers can never be compensated by the diligence of mothers. Again, we despise children if we are not at the pains to understand them, and we cannot understand them unless we love them. “All children are alike” is about as true as that all men are alike. Each child has his characteristics, and presents the strange complex mysterious picture of a human soul. Each has his peculiar potentialities for good or evil, each is affected by heredity as well as by environment. God is at work in each. “Take heed that ye despise not one of these little ones” [Matthew 18:10].

“Offend not.”—“It were better that a millstone were hanged about his neck and he cast into the sea than that he should make to stumble one of these little ones” [Luke 17:2]. The infamy of such deliberate wickedness is rare. Seldom does the shameless mother wilfully pollute her little daughter, or the most brutal father train his son in villainy. But the stumbling block is often cast in a child’s path by carelessness. Words hastily spoken, acts thoughtlessly done in the presence of children, become stumbling blocks to them, with their minds sensitive to impressions, their quick power of imitation, and their instinctive reverence for their elders. Evil example, passionate temper, untruthful ways, little hypocrisies, unguarded conversation, worldly maxims, words which speak lightly of holy things or mock or rudely criticise child-like faith, even the look or gesture or smile which suggests ridicule of some early habit of piety—all these are stumbling blocks. Something within the child shrinks or is startled. What is that but the witness of the Spirit? Oh, it is difficult enough for the little one to walk with tottering feet. To cast the least stumbling block in its way is a refinement of cruelty which the most thoughtless would scarcely excuse. Such cruelty to a child is irreverence to the Spirit of God.

“Hinder not.”—“Forbid them not to come to Christ” [Matthew 19:14]. Some thing within inclines a really child-like child to come to Him. That something is the witness of the Spirit. Hinder it not. Speak not of Legislator, Exactor, Judge, but of Giver, Saviour, Friend, the One Being in the universe not to be afraid of. Say not:—Be good or God will punish you; say rather—Be good for God loves you. Hinder not your child by making the Bible a lesson book, Church attendance an irksome duty, Sunday a day of restriction, saying prayers a morning and evening task; but let these things be to our children, as to us, a delight. They would come to Christ if we would show them who and what He is. Let the picture we present be that of Him who in baptism “took them up in His arms, put His hands upon them, and blessed them” [Mark 10:16].

If these be the negative sides of our duty, what is the positive side? If we believe that, notwithstanding the downward tendency, which is the taint of human nature, fallen but not corrupt, there is a witness of the Spirit within, our aim will be to appeal to that witness, as to ear that can listen, eye that can see, and voice that can answer. This is our main position in a paper which deals throughout with the treatment of the average child-like Christian child, not with the child of exceptional weakness or wickedness, who needs exceptional treatment.

What is the religion of a Christian child? Let us always remember that it is the normal type of Christ’s religion. “Become like little children,” He said to the men who first followed Him. One fears that there is a tendency in this day to reverse Christ’s teaching, and to impress on children the religion which belongs to men. Indeed it has been said with something of truth, that “nine children out of ten do not get any real hold of religion, and the one in ten who does, gets hold of it in a wrong way, and becomes self-conscious, pedantic, and unchildlike” [Twenty Sermons, by Rev. Phillip Brooks, Rector of Trinity Church, Boston, U.S.A.]. The conversion of children is not to be our aim, it may be that it is we who need conversion to become like them.

[Editor’s note: Mason boldly states that we do need to become like children. “Can any of us love like a little child?” Mason asks, on p. 43 of Towards A Philosophy of Education.]

For, in the words of the same writer, “whatever may be said for or against the modern religious idea that adult conversion is the type and intended rule of Christianity, it ought to be readily admitted that the idea of Christian childhood is that it needs no conversion.” I take it then that stripped of all reference to a prior state of existence, the beautiful words of Wordsworth in his great ode express a profound truth;

Trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home. [Ode: Intimations of Immortality]

[Editor’s note: Mason quotes this poem three times in Home Education—on p. 11, 12, and 162. It is likely that Blunt drew this reference from his reading of Home Education.]

Of that home they bear some traces in their innocency. “Become like little children.” This, then, is our Master’s bidding. There is much in child-like children that resembles Him. We may copy their innocency. “We may,” to quote another’s words, “study their quick forgiveness of injuries, their thoughtlessness of self, their calm reposing confidence, their carelessness of the things of the world, their unambitious contentment, their tender yearning affection, above all, their true humility. They have come to us from the Father of Spirits. One day they will be presented before the presence of His Glory. Woe be to us if they are not presented blameless!” [Sermons, by the author of Tracts for the Times]

What suggestions may be offered respecting that training which best may co-operate with the Holy Spirit within them?

[Editor’s note: In the preceding sentence, Blunt admonishes the parent to “co-operate with the Holy Spirit” in the education of his or her child. This anticipates Mason’s formulation of the Great Recognition two years later. First, in March, 1891, Mason echoes Blunt’s precise statement:

All our teaching of children should be given reverently, with the humble sense that we are invited in this matter to co-operate with the Holy Spirit; but it should be given dutifully and diligently, with the awful sense that our co-operation would appear to be made a condition of the divine action; that the Saviour of the world pleads with us to ‘Suffer the little children to come unto Me,’ as if we had the power to hinder, as we know that we have. (PR2, p. 144)

Then in June, 1892, Mason fully articulates the Great Recognition:

… here is the great recognition which the educator is called upon to make. God, the Holy Spirit, is Himself the supreme Educator of mankind…

… above all, he recognises the divine co-operation in the direction, teaching, and training of the child. (PR3, pp. 357-358)]

(1) Recognise the idiosyncrasy of each child, yet submit to no fault as though, because it is hereditary, it is inevitable or incurable. God is on the side of the better self in each of us, and, therefore, He is against all that would deform or defile it, and God, not Satan, is Omnipotent. Reason, affections, conscience, will, must each be trained, with the conviction that God is Himself engaged in the same education and that God bids us work with Him, bids us love His children as He loves them.

(2) We must train the reason. At first we must inculcate obedience to parent and to God, implicit and unhesitating, on the ground of reverence, gratitude, affection. As the child grows older the reason for specific acts of obedience will be given, in order that the child may trust our judgment, as well as respond to our affection: so with religious truths—at first simple, plain, dogmatic statement of what is to be believed; then, as years go on, the grounds on which it rests will be explained; that the whole nature of the child may respond, and mind, as well as affections, be quickened. Therefore within limits we shall encourage questions which the marvellously inquiring mind of the thoughtful child is always suggesting—I say within limits, because every one knows that there is a mere inquisitiveness which is neither childlike nor simple. This training of the mental faculties will be carried on patiently and wisely with the deep conviction that the reason is the sphere of the Holy Spirit’s work, as well as the spirit.

(3) Train the affections. How loving is a childlike child! How quick to respond to love whether of God or man! Such love may be the fruit of unconscious faith in Him whose name is Love, as it certainly is a witness of some share in the blessings of His Incarnation. Never check it. Guide it to worthy aims and objects. Let it develop into pity, gentleness, and self-denial for others. Let it express itself in cheerful obedience, willing service. It is one striking characteristic of children that they do admire and love what is beautiful in the world and in those around them. They will instinctively love, admire, and reverence that which is infinitely lovely in Christ. Set before them the vision of the Lord Jesus, and “when He appears in His love and beauty once again little children will greet Him with their hosannas.”

[Editor’s note: Interestingly, while Mason often speaks of instructing the conscience, she does not speak of training or instructing the affections.]

(4) Train the conscience—It is a germ which needs developing, a witness of the Spirit within, which needs instructing. Oh, what wisdom and love does this work of ours require! How can we touch this most sensitive spiritual organ without destroying something of its sensitiveness? Left to itself, conscience may develop irregularly and become a capricious guide; overtrained it may become morbid; in the one case fanaticism, in the other religious hypochondria, may be the issue. One word of caution, one word of counsel must here suffice. Never discuss questions of casuistry before children. Do not magnify trifling faults as if they were sins. Quicken, instruct, develop their enthusiasm for what is noble, rather than their hatred for what is base. Surround them with what is lovely, cheerful, bright, with happy associations and sweet influences. The young child-plant needs sunshine more than rain. The Spirit’s testimony within is a positive testimony. He beareth witness not merely that they are not children of wrath, but that they are the children of God.

(5) Train the will.—“I think, I love, I ought, I will,” are the stages that prepare for action. The will is the executive faculty. “Force or weakness of character is determined more by the will than by the reason or conscience.” [Home Education, Charlotte Mason]

[Editor’s note: In the preceding paragraph, Blunt explicitly cites Mason’s Home Education for the first time. However, although he uses quotation marks, the quoted text does not appear in Mason’s volume. His text is possibly a very loose paraphrase of Home Education p. 319. In any event, this specific citation shows that Blunt was inspired by Mason’s writing.]

Self-control, government of the passions and temper, yielding obedience, setting in motion conscious action—all these are effects of the will. Impress on the child that he can do what he wills if he asks God’s help, and therefore that he ought to do what is right and to do it promptly. Begin early to train in habits of resolution, courage, action. The faltering, hesitating, postponing habit which dallies with the will, and tampers with the conscience, is certain to enfeeble the character; and weakness is a danger much closer to childhood than positive wickedness. On the other hand, the stubborn will, which makes a child intractable, disobedient, contrary, even defiant, must be bent by gentle firmness rather than broken by violence. Passionate treatment is always out of place, for passion is no cure for anything—it is always a disease, not a remedy. Earnest appeals to reason, affection, and conscience incline the will towards submission, and each act of submission followed by obedience is a step towards habit. Oh, how difficult is this guidance of a human will—that sacred prerogative preserved to us in the wreck of fallen nature. Yet the task is not hopeless, if we pray and strive with the conviction that God’s Spirit dwells in each child to make him “to will” as well as “to do after His good pleasure” [Philippians 2:13].

(6) But, above all, the soul needs training. the nascent germ of spiritual life, must be quickened and developed—not implanted, because we would fain believe that as a fruit of the Incarnation there is in each child some ray of “the light that lighteth every man” [John 1:9], a witness of the Spirit whose presence was assured at his baptism. May I offer suggestions and warnings?

In dealing with the child’s faults and sins let us be careful that we make neither too little nor too much of them. While such expressions as “children will be children,” “boys will be boys,” are often excuses for children and parents to tolerate faults they ought to cure, there may be a vehemence, exaggeration, chronic fault-finding which irritates and discourages children and impresses them with the sense of injustice. Here again the principle for which we are contending holds true. Make a solemn appeal to the better nature within, which is the voice of the Spirit; show the child the unhappiness of doing wrong and being wrong. Win rather than scold the child into repentance. If you inflict punishment let it not be arbitrary, but as far as possible consequent upon the offence itself. Often the wisest punishment is the exclusion of the child from the society of parents, teachers, brothers and sisters during the interval of hardness, sullenness, or defiance, and his restoration on the expression of sorrow. Upon any confession of wrong, let a prayer be offered with the child as well as for the child for God’s pardon, and then let the subject be dismissed altogether. The Spirit of God within will bear witness that adoption implies more than Fatherhood. He will also witness that since God is a Father, He forgives.

Again, be careful not to teach children too much theology, but let what you teach be simple, plain, dogmatic. The scholastic doctrine of the Trinity is beyond them, but the equal love of Father, Saviour, Comforter will win them. Theories of Atonement, Justification, and Sanctification are out of place, but the love of God in sending His Son, the love of the Son in dying for them, and the presence of the Spirit in their hearts to teach and to bless them—these truths they can receive from their early years. Surely the wise reticence of the Church Catechism is very instructive. The Apostles’ Creed and the simple exposition which follows will form the best framework of the child’s theology. Mere exhortations to be good are not enough. Teach them of God, for it is “in the knowledge of God that eternal life standeth” [John 17:3] whether in children or in us. Yet throughout all be absolutely truthful in your religious teaching; therefore do not give traditional teaching which you have cast off yourself, thinking it will do for a child. There may be reticence, but there must never be insincerity in our teaching. The difference between the religion of a man and the religion of a child is not the difference between truth and falsehood, but between the full and the partial reception of truth. God is the God of truth. If we may not “do evil that good may come” [Romans 3:8], we may not speak falsehood that truth may conquer.

Train your children in habits of devotion. Take them to church as soon as, but not before, they understand something of reverence to God and His House, and can enter into the meaning of some parts of the service. Bring them to children’s services and public catechising, that ancient godly custom now happily almost universally revived. Children will readily love the church, even the place itself, with its services, its brightness, its singing, its expressive ritual; for there is a poetry in most children which naturally inclines to love the beautiful, and has in it no taint of self consciousness or sentimentalism. Above all, I need scarcely say, teach them in their earliest years private prayers; take care that these prayers are really child-like, yet beware of their being childish. The child’s prayers should develop with the child’s development, and correspond with his growing needs; but how often has one found that the prayers of Confirmation candidates have been those taught in early childhood, the only relic of their nursery years! I believe children as a rule love their prayers, and, if well taught, are often examples of reverence to their elders, for the intuitive reverence in childhood and early youth, without affectation and without superstition, is yet another witness of the Spirit of their Father which speaketh in “them.”

Again, self-consciousness in the religious life of children is to be deprecated as foreign to their nature. The more of spontaneity and naturalness the better. Do not then encourage them to talk too much even of their feelings towards God. It is only too easy to make good children hypocrites, by inducing them to say what we expect them to say or to feel what we expect them to feel. There is some danger in examining a child about his motives, affections, feelings. It is well to respect the shyness which may cover an innate holy sensitiveness.

Tear not away the veil, dear friend,

Nor from its shelter rudely rend

The Heaven-protected flower;

It waits for sun and shower

To woo it kindly forth in its own time,

And when they come, untaught, will know its hour of prime. [“Shyness,” Lyra Innocentium.] [John Keble]

Once more, do not expect religious maturity in a child. There is a saintliness which is really childlike, but it is unlike the saintliness of men and women. Precocity is as unwholesome in the things of heaven as in those of earth. Avoid then forcing a child through your own modes of thought. The Spirit’s method which we ought to reverence is that of gradual development—“first the blade, then the ear, after that the full corn in the ear” [Mark 4:28]. It is of childlike children in their unconscious simplicity, not of unchildlike children in their self-conscious precocity, that the Lord Jesus said, “Their angels do always behold the face of my Father which is in Heaven” [Matthew 18:10].

I have spoken in this paper of childhood and early youth, not when wasted, ruined, depraved, but as, thank God, we may often see it in English homes, bearing witness of the work of God’s Spirit within. To what ought such childhood to lead? Begun in Baptism the childlike life we have described finds its climax in Confirmation. Then it is, when boyhood and girlhood emerge into a mature stage, when temptation increases and passions grow stronger and the world more fascinating and self more exacting, that the unconscious faith and love and devotion of early years may—and indeed ought to—be exchanged for a consciousness befitting the development God ordains for His child. Then the youth shall know more fully in Whom he has believed; then he shall awake to a love which becomes a conscious motive within and expresses itself in a deliberate surrender. Then it is that the Spirit bears a yet stronger witness of the Divine adoption as He is poured out in abundance in and through the holy rite of Confirmation, and the life of the soul renewed and quickened, awaits, expects, craves the strengthening and refreshing which becomes its blessed privilege in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Body and Blood. There we may leave him whose career we have been tracing in his earlier years, entering fully into the blessedness of his heavenly inheritance in the Church on earth; and as we behold him kneeling at the Table of His Lord, we may expect with hope as we pray with faith that the promise of his baptism may be fulfilled—“He shall not be ashamed to confess the faith of Christ crucified, and manfully to fight under His banner, against sin, the world, and the devil; and to continue Christ’s faithful soldier and servant unto his life’s end” [Anglican Book of Common Prayer].

Editor’s Note: The formatting of the above article was optimized for online viewing. To access a version which is formatted more similarly to the original, and which includes the original page numbers, please click here.

One Reply to “Reverence for the Work of the Holy Spirit in Children”

Thank you! I really was struck by this: “But the stumbling block is often cast in a child’s path by carelessness. Words hastily spoken, acts thoughtlessly done in the presence of children, become stumbling blocks to them, with their minds sensitive to impressions, their quick power of imitation, and their instinctive reverence for their elders. Evil example, passionate temper, untruthful ways, little hypocrisies, unguarded conversation, worldly maxims, words which speak lightly of holy things or mock or rudely criticise child-like faith, even the look or gesture or smile which suggests ridicule of some early habit of piety—all these are stumbling blocks. Something within the child shrinks or is startled. What is that but the witness of the Spirit? Oh, it is difficult enough for the little one to walk with tottering feet. To cast the least stumbling block in its way is a refinement of cruelty which the most thoughtless would scarcely excuse. Such cruelty to a child is irreverence to the Spirit of God.”