Teaching Cardboard Sloyd

After discussing the principles of sloyd in my first article, we looked at how to begin paper sloyd in Forms 1b and 1a. My previous article ended with this quote from Mr. Devonshire: “It should be clearly understood that it is Card-board Sloyd that is considered essential for the full development of the child…” In this article, we will look at the specific benefits that come from a progressive course of sloyd, and then we will conclude with the “how-to” of cardboard sloyd in Forms 2 through 4.

After discussing the principles of sloyd in my first article, we looked at how to begin paper sloyd in Forms 1b and 1a. My previous article ended with this quote from Mr. Devonshire: “It should be clearly understood that it is Card-board Sloyd that is considered essential for the full development of the child…” In this article, we will look at the specific benefits that come from a progressive course of sloyd, and then we will conclude with the “how-to” of cardboard sloyd in Forms 2 through 4.

For the sake of simplicity we will follow and expand on the benefits laid out by Miss Pennethorne in her article “Cardboard Sloyd” (1906). She gives three categories of benefits that result if sloyd is used to “its fullest educational value”: physical, mental and moral. We will look at them one by one.

Physical

Miss Pennethorne lists the physical benefits as follows:

1. It trains the eye to accuracy (accuracy being understood as absolute, not relative) in (a) drawing a straight line, (b) measuring distances and angles, (c) cutting on the line drawn.

2. It trains the hand to follow the guidance of the eye, and to obey exactly the impulse of the motor nerves transmitting the message of what the hand is required to do.

3. It strengthens the muscles of the hand by exercise. (1906, p. 3)

We have already seen in Form 1a how using the knife can lead to accuracy and meticulous control of the hand, following the judgements made through the eye. The student learns to control different muscles for different results in the same way that he might control different large muscles in his body. These controlled movements allow him to become the master of his tools. I have found several references to links between Swedish Drill (developing control of specific muscles of the body) and sloyd (developing control in specific muscles of the hand) and the two working together for optimum physical benefit:

This fact is recognised in the teaching of Swedish drill by the best methods, in which the pupil is told which special muscles each exercise is intended to develop, and so he can concentrate his thought on those particular muscles, thus gaining the fullest possible benefit from the exercise. (Pennethorne, 1906, p.6)

It may be said that a perfect system of handicrafts tends to increase and refine on individual lines the powers of mind and body already developed by a perfect system of gymnastics.

We can see how the finger stretching and clasping paves the way for the individual use of the ten fingers, when binding or glueing a Sloyd model. The nerve and decision gained in the grasping and suspension movements help in the mastery and use of tools; while wrist exercises considerably ease the sweeping movements so often needed in wood-carving. (Devonshire, 1905, p. 9)

That same intentional movement increases the student’s powers in drawing specifically so that he might make accurate representations of what he sees. This power is what brings us to the second category of benefits.

Mental

Mr. Russell, who I believe introduced the PNEU to the philosophy of sloyd, shows plainly the link between right work and right thinking:

The simple straight line is the very basis of all construction, and enters, in its various combinations, into nearly everything our hands can fashion—and yet how few of us can even draw it on paper, much less produce it in wood! We are satisfied with an approximation, with getting it nearly right. And is not that the characteristic of most of our thought, our action—that we are satisfied if we can keep pretty close to the line of the ideal? But must not the boy who learns to cut accurately learn to think accurately? Is it not thought that guides the knife? (Russell, 1893, p. 328)

In The Parents’ Review article “The Value of Art Training & Manual Work,” Mrs. Steinthal concurs that sloyd develops thinking skills that are as important as the manual skills. She says that manual training:

…conveys to the mind that it is to impart power and skill to the hand; but it is not altogether so. Power and skill of hand are much, but not everything. The eye has to take in information, of which the mind forms a mental picture, and, guided by practical experience, it selects what is needed. The mind seeks to express in the concrete the picture it has formed. It is, in fact, training in thought by other means than verbal language. Its aims are those which are, or should be, the aims of all general education, the acquisition of knowledge and development of power. It has therefore a right to a place in education. Hand work is not introduced in home and school teaching as technical instruction in its strict sense. (Steinthal, 1897, p.414)

So not only does the practice of sloyd develop the ability to think rightly and control the use of our hands, but it also aids in the use of the imagination. The student will learn to imagine a three-dimensional object from a two-dimensional diagram and then learn to draw a two-dimensional diagram from a three-dimensional model. By combining reasoning abilities, imagination, and mental control with manual dexterity, the student will grow in his ability to make and do what is necessary.

The student can also take these mental powers into other areas of his schooling. His reasoning powers and measuring skills apply to math. He becomes better at nature journaling because of his increased ability to make his hand draw what his eye sees. He takes pride in his Book of Centuries because he can accurately reproduce artifacts of interest on his page. He has an understanding of the foundation of architecture and the confidence that comes from accomplishments made by his own power. Mr. Devonshire calls that confidence “moral progress,” (1905, p. 9) which bring us to the final benefit we can expect from diligent lessons in sloyd.

Moral

This was the area I least expected when I began my research several years ago, but it is the one that I believe to be the most important. During his presentation to the Woodward branch of the PNEU, Mr. Russell asks hypothetically what would a child learn if he were educated on sloyd alone. He says:

… they would certainly train their eyes to real power in seeing, and their hands to real power in doing, and … be sure at least of a sound body. But that is not all. They would be doing something too towards a sound mind… they would learn… to be orderly, accurate, attentive, industrious, thoughtful, and self-reliant—nay, I will go even further, and add truthful. Orderliness, accuracy, attention, industry, thoughtfulness, self-reliance, truthfulness—verily a list of nearly all the virtues! (Russell, 1893, p. 328)

But this “moral progress” doesn’t apply to the student alone; it also applies to his relations with people outside of himself. Russell puts the idea well in this lengthy quote:

You will be giving them a fuller understanding, and therefore a fuller pleasure in some of the commoner everyday things of life, and in the underlying principles of innumerable human productions; but, above all—and sometimes, when I look about me, I think that this gain alone should suffice to give Slöjd an honourable place in our schools—you will, if your methods are sound, and your own heart is right, give them respect and love for all honest hand-work and honest hand-workers, and so save them from that blight of shame which still fastens on many and many a human being at the thought of doing any honest work whatever, and on still more perhaps at the thought of working with their hands!

Ladies and Gentlemen, you must pardon me for saying in this connection that, in my opinion, one of the first steps towards making this world a happier place is to get men and women not only to say but to believe—and belief is practice—that no work that is essential to the continuance and well-being of humanity is below the dignity of the best or wisest of us, and further, that all work that is unpleasant, or repulsive, or involves danger, must, within certain obvious limits, and in the absence of perfected machinery, be shared unshirkingly by all. (Russell, 1893, pp. 332-333)

In this idea I see an illustration of the Christian body:

Don’t think you are better than you really are. Be honest in your evaluation of yourselves, measuring yourselves by the faith God has given us. Just as our bodies have many parts and each part has a special function, so it is with Christ’s body. We are many parts of one body, and we all belong to each other. In his grace, God has given us different gifts for doing certain things well. (NLT, 2013, Romans 12:3b-6)

Craftsmanship has long been stigmatized and it is simply wrong to perpetuate this idea that educated people don’t get their hands dirty. There is dignity in every dirty job and every kind of rough work. It may be that the child’s best way to serve is in some honest handwork.

But you will be doing more than this. You will be affording them an opportunity of showing, before it is too late, where their special powers lie—in the head or in the hand—and helping them to find an answer to that fateful question—that chance too often mis-answers for us—What shall I do with my life? (Russell, 1893, p. 332)

If you still had any doubts about the importance of continuing sloyd, I hope I have finally dispelled them. And so now we move on to the “how-to” for cardboard sloyd.

Cardboard Sloyd Lessons

In his article, “Harmonious Relations Between Physical Training and Handicrafts,” J.W. Devonshire gives a basic progression for cardboard sloyd lessons:

To each child is given a thin piece of card-board, a sloyd knife, a ruler marked off into centimeters, and a strip of glued binding. After a few essays in cutting and binding the child begins simple models, such as mats, key labels and other flat articles, which by gradual progression lead on to slip covers, boxes, portfolios, photograph frames, and eventually to bookbinding. (Devonshire, 1905, p. 8)

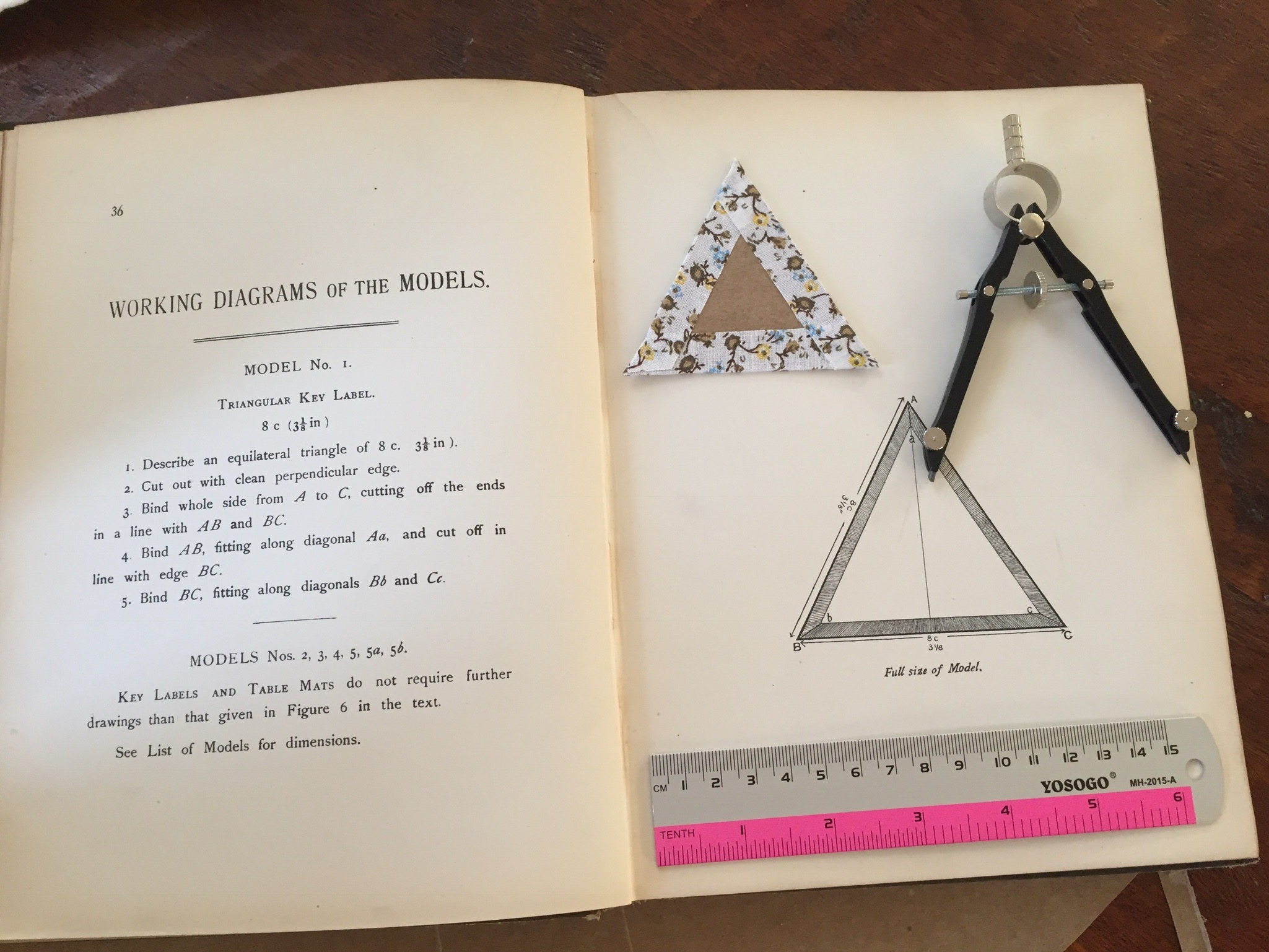

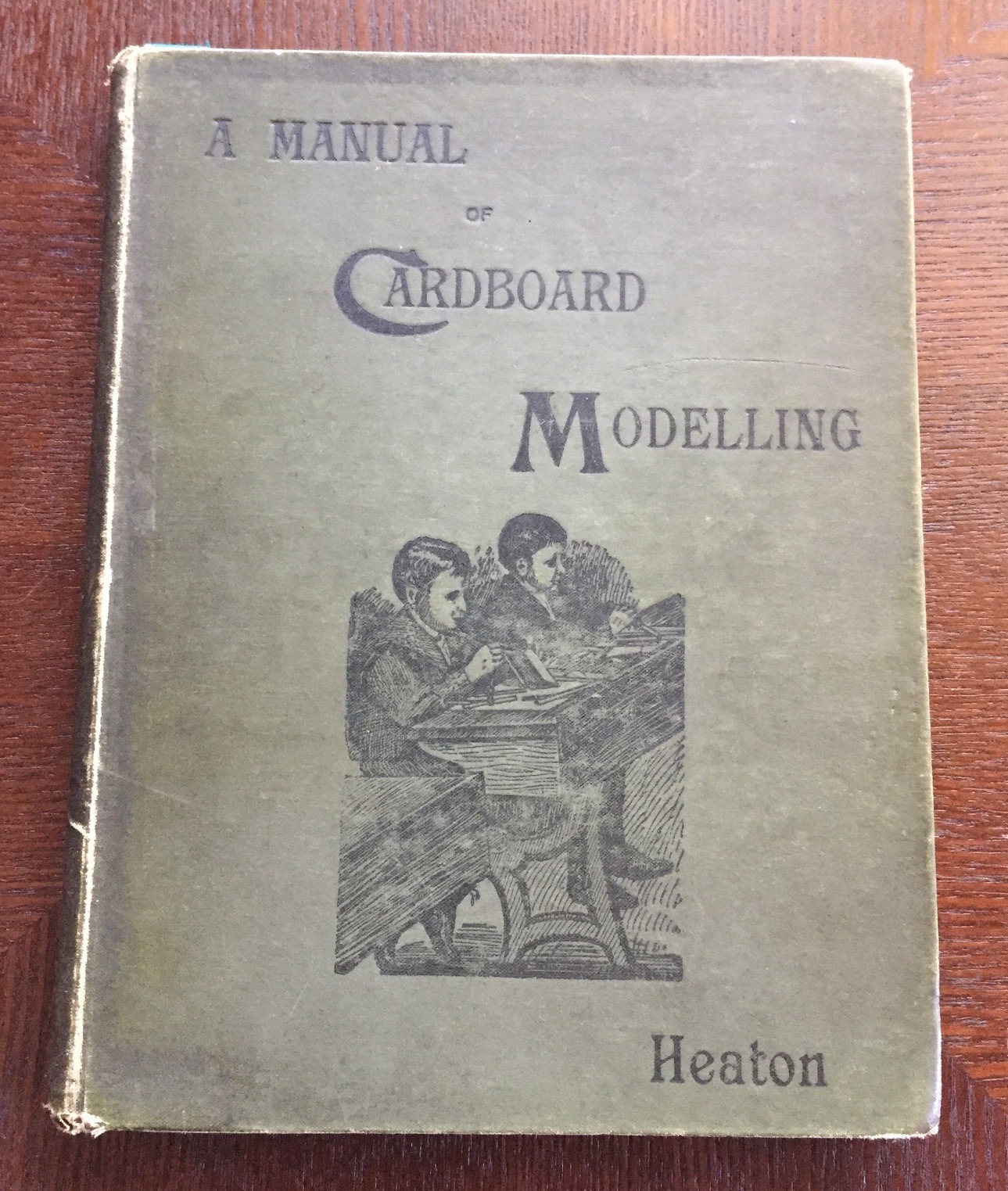

This is exactly the order given in the book by William Heaton that was used for cardboard sloyd in all the programmes we have from Mason’s lifetime. I believe that Heaton’s book set the standard for cardboard sloyd in the PNEU. Mrs. Steinthal praises Heaton’s book, and cites an interesting passage in which Heaton quotes Rousseau:

This is exactly the order given in the book by William Heaton that was used for cardboard sloyd in all the programmes we have from Mason’s lifetime. I believe that Heaton’s book set the standard for cardboard sloyd in the PNEU. Mrs. Steinthal praises Heaton’s book, and cites an interesting passage in which Heaton quotes Rousseau:

I would press teachers very earnestly to study Mr. Heaton’s book, which is so carefully prepared that any adult could work the models without any previous training, and then teach it to her pupils… Rousseau preferred that Emile learnt to build highways rather than make flowers or porcelain. He says, “Let us choose a respectable trade, but let us ever remember that there is no respectability without utility.” Mr. Heaton maintains and proves that “cardboard work is a step, and a good step, in this direction.” It specially helps to form habits of order, exactness, neatness and cleanliness, and forms a bridge over which the boy passes to Sloyd at the age of eleven or twelve. (Steinthal, 1894, p. 925)

So to understand cardboard sloyd at it’s best, we need to use Heaton’s A Manual of Cardboard Modelling as our guide.

Mr. Heaton said that the purpose of cardboard sloyd is:

1.—To strengthen the body, to invigorate the constitution of the child, to place the child in hygienic conditions favourable to general physical development. [Hygienic here means conducive to good heath.]

2.—To give him at an early age the qualities of readiness, quickness, and manual dexterity—that promptness and certainty of movement which, while most valuable to every one, is especially necessary for such pupils as are destined for some manual profession. (Heaton, 1894, p. 9)

Form 2

In Form 2, handicrafts move from morning lessons to afternoon occupations. By this time the student should already have control over his knife and skill in accurately measuring and cutting, but these lessons are still not handed over to the child without adult supervision and oversight. In the quote above from Mrs. Steinthal, we see that she recommends that the teacher study the book herself and learn how to do the models, then teach the students. If the student has a solid foundation in paper sloyd, and the teacher has taken the time to ensure that the new skills are understood, then the student will soon be ready to do models completely on his own; the teacher will only need to be on hand for questions and difficulties.

In Form 2, students were expected to complete four perfectly executed models per term. The first models are key labels, followed by mats, book covers, trays, and boxes. It seems likely that the students were doing each model more than once before being allowed to move on to the next project. Though, remembering the principles, the child should not be required to do the same model so many times that he becomes discouraged. Lessons were still short (20-30 minutes), and several new skills were introduced, causing the student to work more slowly and more carefully compared to the previous year’s work. The new skills include:

- Transitioning to the metric system for increased accuracy when increasing or decreasing the size of the model.

- Using thicker paper and learning the appropriate amount of pressure to score it without cutting through.

- How to bind edges with bookbinding tape.

So while the initial models seem quite simple, students are building up the skills which will allow them to be successful with the more complicated models.

Form 3 and 4

Forms 3 and 4 continue along the same lines as Form 2, but doing six models per term. Models increase in difficulty because of the more complicated geometric shapes used in the diagrams. We do not know if sloyd was done in each term. If it was, models from Heaton’s book would be exhausted by the second year of Form 3, but we can see it scheduled in Form 4 as well. Because of that, I think it is likely that sloyd was not scheduled every single term in Forms 3 and 4.

The last skill to be mastered in cardboard sloyd, before moving on to wood sloyd or bookbinding, was the ability to draw a diagram from a geometric model: converting a three-dimensional object to a two-dimensional drawing. Plans for these models, to be made by the teacher, are included in the appendix of William Heaton’s book.

Practical Tips

The “cardboard” used for cardboard sloyd is simply thick cardstock. A variety of thicknesses can be used, including thin chipboard, like the type used for retail gift boxes. Thicker than that is not recommended. Our preferred cardstock is 110 lb (300 g/m2); it is readily available in craft stores and comes in a variety of different colors.

The same craft knife used in Form 1 can be used for cardboard, but if wood sloyd is the goal for that student, it may be worth purchasing an actual sloyd knife and learning how to sharpen and care for the knife. I remind the reader that both types of knives are quite sharp and, while I do allow my own children in Forms 1 and 2 to wield them, I always ensure that the knives are kept out of reach when lessons are over.

For binding we have many more options than the students would have had a hundred years ago. In addition to bookbinding tape (which didn’t always come “pre-gummed” at that time) we have washi tape, in many patterns and widths, as well as colorful duct tape and masking tape. I think it is perfectly fine to take some liberties here with choice in materials. Bookbinding tape can be quite expensive, especially if it has to be shipped to the home. The other kinds of tape are much less expensive and are readily available at most craft stores.

At this time William Heaton’s book is not readily available, but I do hope to bring it to the Charlotte Mason community soon. Until then, I recommend that you go back through the later models in the Rich book and practice some cutting with a knife. Unfortunately there is no other title I can recommend for teaching cardboard sloyd.

Conclusion

I hope this series on sloyd has been interesting and useful. My family enjoys sloyd quite a bit and I have enjoyed sharing my own experience and research with you. I will close with this little stanza written by the students at Scale How which shows the lighter side of training in sloyd:

Do you want to study

What sloyd and carton mean?

Be a Scale How student,

On models you’ll get keen,

Just use your knife quite freely,

And cut your finger so,

Here is scope for genius

And works like hang! dash! blow!

References

Devonshire, J. (1905). Harmonious relations between physical training & handicrafts. In L’Umile Pianta, March, 1905 (pp. 8-11). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Heaton, W. (1894). A manual of cardboard modelling. London: O. Newmann & Co.

NLT. (2013). Holy Bible: New living translation. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers.

Pennethorne, R. (1906). Cardboard sloyd. In L’Umile Pianta, April, 1906 (pp. 3-6). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Russell, C. (1893). On some aspects of slöjd. In The Parents’ Review, volume 4 (pp. 321-333). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Steinthal (1894). Aunt Mai’s budget. In The Parents’ Review, volume 4 (pp. 922-931). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Steinthal (1897). The value of art training & manual work. In The Parents’ Review, volume 8 (pp. 414-418). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

10 Replies to “Teaching Cardboard Sloyd”

Fascinating article – as usual. Thank you Brittney! I was especially intrigued with the “moral” section.

Thank you for reading and commenting, Lisa. I think the idea of the moral benefits in Russell’s article is what first got me hooked!

Thank you, Brittney, for equipping me for sloyd lessons as I head into the new school year with my older students. One can only imagine my boys’ glee at each finding a new Morakniv along with the usual new notebooks and pencils on their first day.

Your reprint of “A Manual of Cardboard Modelling” will be most eagerly awaited and your inclusion of moral habits had me “all ears” as I particularly love that intersection of the practical with the profound in a CM education. I’m most likely late to this party but I’ve finally put two and two together to realize the preface to Heaton’s book by T.G. Rooper is none other than the beloved House of Education inspector and PNEU proponent, Mr. Rooper(!) who had attended sloyd classes at Naas himself. The final chapter of Mason’s “Formation of Character” is a tribute to that modern educator in which she tells us, “He delighted to turn out a perfect wooden spoon on his Sloyd bench, and was most keen to learn leather work by watching the students at the House of Education” (p. 424).

Thank you again for sharing your research with us.

Richele,

I hope your boys are not the only ones delighted to find a shiny new blade among their back to school supplies.

I was also intrigued to find that the Mr. Rooper who wrote the preface to Heaton’s book was the same Mr. Rooper known personally by Miss Mason! When examining the relations between these progressive leaders in education, the connections are remarkably close. Fascinating!

Thank you for sharing this exciting connection with our readers.

Brittney

Thank you for this series! I’m really enjoying our initial sloyd lessons (my son is in 1B). I’m wondering: Is the paper you recommended here (110 lb) also what you would recommend for beginners just working with paper folding? We took your advice and have started with 6×6 in. pre-made squares of paper. These are origami papers that I ordered. They are easy to fold but I have been wondering if they are flimsier than the “real stuff” should be? Thanks in advance!

Hi Stephanie,

I am so glad you have enjoyed the series and your lessons thus far in paper folding.

I understand what you mean about the paper being flimsy, but I recommend that you stick with it, at least until the skill of neat and accurate folding is well in place. You can go to slightly thicker paper with about the feel of printer paper, but I don’t recommend cardstock until you are ready for paper sloyd. The 110lb paper is too thick even for paper sloyd. It requires scoring to fold well, so it would be a poor choice when folding is the skill to be worked on. I think of the origami models of being more fun, but less serviceable. I hope that helps!

Brittney

This is a wonderful article which, of course, made me want to track down A Manual of Cardboard Modelling! Am I correct in understanding it is not currently available anywhere?

Thank you so much for all the work you are doing!

Lynne,

I am so glad you are excited about cardboard modelling! But yes, Heaton’s book is currently unavailable. I am working with Living Library Press to get it republished, but I don’t have a time frame yet. We will share it on CMP as soon as we get a date!

Brittney

Do you have a favourite knife for younger students? Thanks!

Cardboard modeling mentions enamel paper. What is a good substitute for that? I used bookbinding fabric in the past but was hoping for a different option