The CMP Review — Week of October 7

October 7, 2024

“The best method is to be very much absorbed in your own work while the children are playing. Choose some work for yourself which won’t need much concentration on your part, for you can’t expect quiet, but whatever it is let it keep you busy. Then, don’t interfere with their play. Let it be spontaneous and unconscious. Let them invent their own and you will find that it will take very little material to amuse. Then also you will be fostering that happy gift of pleasure in simple things and an absorption and interest in the occupation in hand. Your aim is to let them create their own games, to amuse themselves. This is so necessary for their adult life, for you will be teaching them that their contentment is not necessarily dependent on external pleasures or the praises of the crowd.” (Parker, PR 46, “Games and Wet Day Occupations”)

@tessakeath

October 8, 2024

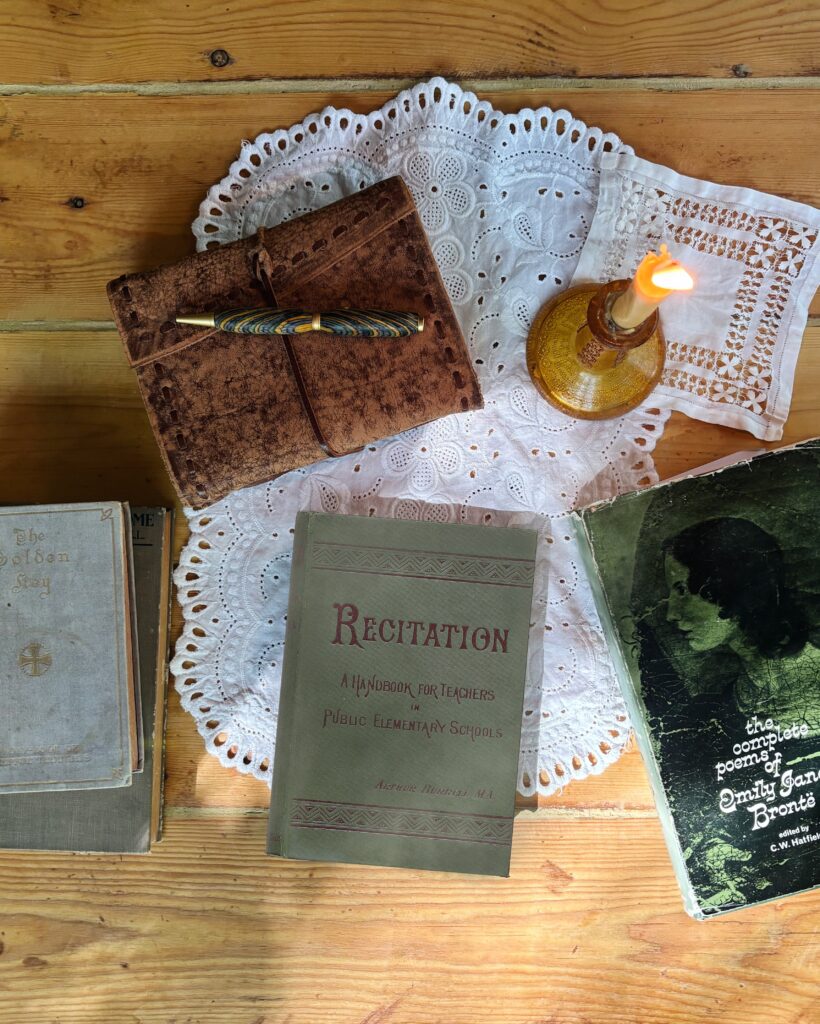

The Concise Oxford English Dictionary defines “to recite” as “to repeat aloud (a poem or passage) from memory before an audience.” It’s from this verb that we get the noun “recitation,” “the action of repeating something aloud from memory,” an art as old as language itself.

Recitation was a standard practice in the British schools of Charlotte Mason’s day. But how was it being approached? How was it being taught? Mason would later claim that “there is no subject which has not a fresh and living way of approach.” Could this be true even of a traditional subject like recitation?

Enter educationist Arthur Burrell. In the very second issue of The Parents’ Review, he would write an article to answer that question. He would show that recitation, too, has a living way of approach. His article would begin a long, fruitful, and synergistic relationship between Burrell and the PNEU.

Burrell’s 1890 article remains unmatched as a call for the reformation of recitation. It is still a fascinating read. But there is one thing even better than reading Burrell’s article. It is listening to it read aloud by audio performer Greg Rolling. This recording we bring you today.

You see, whatever the OED says about “recitation,” Mr. Burrell defines it his own way. Turning the teaching of recitation on its head, Burrell’s timeless piece redefined recitation once and for all as “the children’s art.” Read or listen to it here.

@artmiddlekauff

October 9, 2024

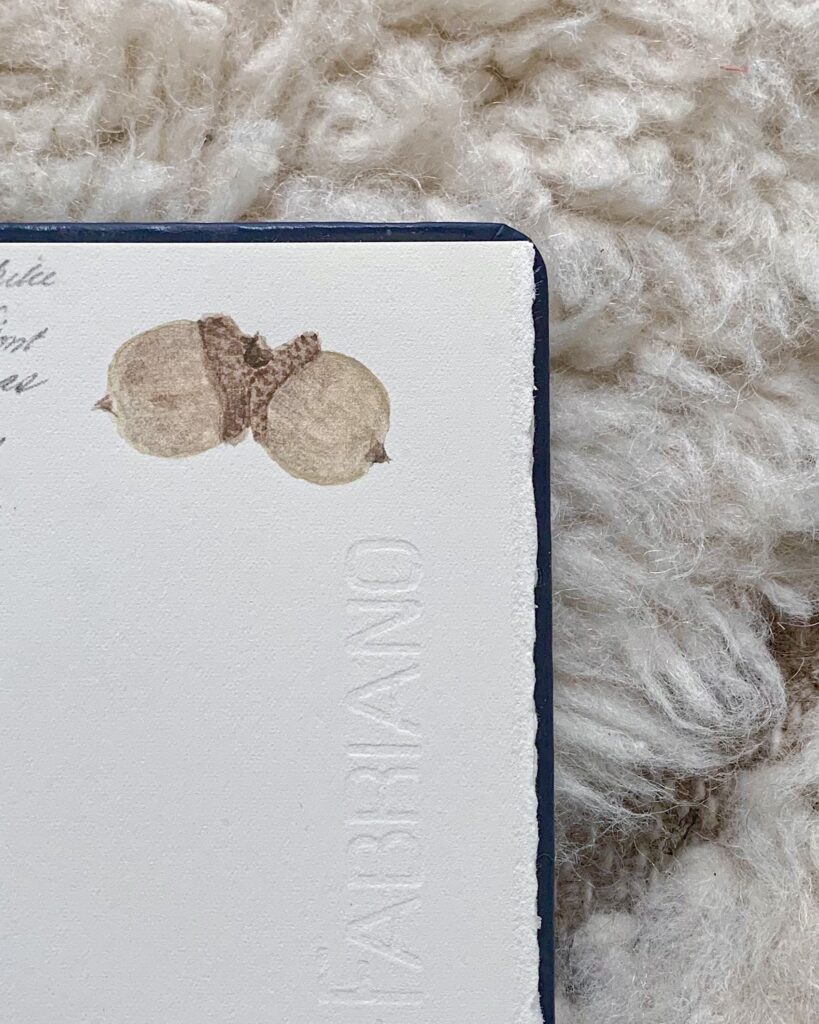

When nature journaling, Charlotte Mason encouraged us to draw “from the round.” But, what does this phrase mean?

Simply put, it’s drawing from the object itself and not copying a drawing or other 2D representation of the object. In this way, we can see the object from all sides and get to know more about it—make friends with it, if you will. We can also determine the composition ourselves, drawing it as we found it in nature.

@rbaburina

October 10, 2024

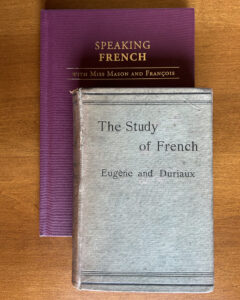

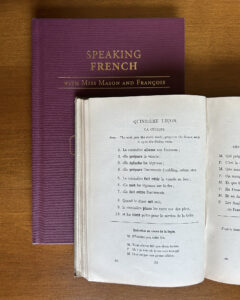

In her 1952 article “Memories of the Past,” Henrietta Franklin recalls her visits to the House of Education in the 1890s. One sentence in particular stood out to me: “The walls also echo to … Mademoiselle Duriaux’s lectures when she first introduced the living method of language teaching (Gouin) and Charlotte Mason felt her students must know this reform.”

This made me think about pages 302–307 of Home Education in a whole new way. In this chapter entitled “French,” Charlotte Mason describes “M. Gouin’s Method” and mentions his 1892 book The Art of Teaching and Studying Languages. It always sounded to me like Miss Mason picked up Gouin’s book and was inspired. But it was not a book that struck her. It was a person: Mlle Duriaux.

It is telling that the appendices of Home Education mention not Gouin’s book, but a book by Duriaux — and that book is mentioned twice (pp. 389 and 399). The book is entitled The Study of French and is written by Alfred F. Eugène and H. E. Duriaux (first edition 1896).

It is fascinating to see the Gouin Series in Duriaux’s book and to imagine her sharing these with Miss Mason, Mrs. Franklin, and the students gathered at the House of Education. Mason saw this demonstration and “felt her students must know this reform.”

The Gouin method has been a part of our home school for many years. We have spent so many hours with the two volumes of the lovely Speaking French with Miss Mason and François by Cherrydale Press. This week one of our graduates joined in for the lesson and with smiles and laughs we recounted the series in French. It was a delightful moment. One might even say it was living.

@artmiddlekauff

October 11, 2024

These are the days when Birds come back —

A very few — a Bird or two —

To take a backward look.

These are the days when skies resume

The old — old sophistries of June —

A blue and gold mistake.

Oh fraud that cannot cheat the Bee —

Almost thy plausibility

Induces my belief.

Till ranks of seeds their witness bear —

And softly thro’ the altered air

Hurries a timid leaf.

Oh Sacrament of summer days,

Oh Last Communion in the Haze —

Permit a child to join.

Thy sacred emblems to partake —

Thy consecrated bread to take

And thine immortal wine!

— Emily Dickinson

@artmiddlekauff

📷: @dave_stillwell

October 12, 2024

Leaf prints: The first two are temporary prints made from the sun and rain. These usually last until the next rain. The third is a permanent print made from a leaf which fell on freshly poured concrete.

@rbaburina

October 13, 2024

Charlotte Mason consistently and faithfully held to the mysteries of the historic Christian faith. In the second of the Anglican Articles of Religion, she read that in Christ, “two whole and perfect Natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one Person, never to be divided, whereof is one Christ, very God, and very Man.”

In keeping with this mystery, Mason often contemplated the divine nature of Christ as well as His human nature. Sometimes she considered both in the span of a single poem. In Mark 3:19b–20, we read that Jesus and His disciples “went into a house. Then the multitude came together again, so that they could not so much as eat bread.” According to Ralph Earle, the modern equivalent would be, “They didn’t even have a chance to grab a bite to eat.”

Could the “Source of all strength” need rest? Could a “a Man, exhausted, faint,” be “our God of mighty works”? And what did the crowds find when they came to that house in Capernaum?

The found one who was truly man, for sure. But Mason affirmed that they were also “to find the Very God!” Read or listen to Mason’s poem “He cometh into an house” here.

@artmiddlekauff