The New Ways and the Old Ways of Education

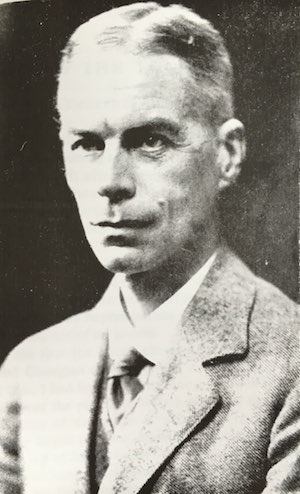

Horace West Household (1870-1954) was the Secretary for Education of Gloucestershire County in 1916 when he first encountered Charlotte Mason’s theory of education. He wrote of that encounter and what followed:

Horace West Household (1870-1954) was the Secretary for Education of Gloucestershire County in 1916 when he first encountered Charlotte Mason’s theory of education. He wrote of that encounter and what followed:

It was in November 1916 that in common with all my fellow directors in education I received from Miss Mason a pamphlet that told the story of the Drighlington experiment… I got into touch with Miss Mason, and then early in 1917 obtained my chairman’s permission to provide five picked schools with the necessary books. The following year I selected twelve more, and after that the new methods spread as if by some beneficent infection, making their way from school to school until there were only thirty that had not adopted them when I retired in 1936. (quoted in The Story of Charlotte Mason, by Essex Cholmondeley, p. 133)

Margaret Coombs referred to Household as Mason’s “ardent disciple” (Charlotte Mason: Hidden Heritage and Educational Influence, p. 248). He was deeply committed to Mason’s ideas and worked tirelessly to promote them within his jurisdiction and across England. He visited Ambleside multiple times, and he understood education in general and Mason’s theory in particular.

Shortly after Mason’s death In 1923, the volume In Memoriam was published. Household was a contributor to this volume. In his writing, the reader is struck by how this educationalist assessed Mason’s place in history:

1. Mason’s impact was revolutionary. “If [parents] observe the progress of their children, and compare the education which they are receiving, with the education which they had themselves, gratitude to the illustrious lady who worked such a revolution in methods and results, should move them to do what in them lies to extend such benefits to all” (p. 183).

2. Mason’s discovery was unprecedented. “[Teachers] were not prepared—we were none of us prepared—for Miss Mason’s epoch-making discovery, the ‘great avidity for knowledge in children of all ages and of every class’ knowledge which is presented to them in more or less literary form” (p.189).

3. Mason found a new starting point. “Miss Mason’s philosophy of education began at the opposite pole to that of her predecessors” (p. 188).

4. Mason rejected the “old ways.” “Though she taught a new thing, a new way, and in teaching had to show the old things and the old ways for what they really are, her criticism left no sting.” (p. 43)

Household believed that Mason’s theory of education was so revolutionary that it would not fade with the sunset of Mason’s life. He wrote, “Our work, her work, is before us” (p. 42). Household predicated Mason’s future impact:

It is not yet the time to measure up her whole achievement. The full harvest is not yet. But there is enough to justify the confidence that posterity will see in her a great reformer, who led the children of the nation out of a barren wilderness into a rich inheritance. The old bidding prayers of our homes of learning rise to our lips. The children of many generations will thank God for Charlotte Mason and her work. (p. 44).

In this and in so many other ways, Household got it right. Across the generations and across the ocean, those words of prayerful gratitude that he predicted have come. I have heard them with my own ears.