What Would Charlotte Do?

Cet article est également disponible en français.

On January 16, 1923, Charlotte Mason entered the next life. I can only suppose that the very next day some new question came up, and a PNEU member asked, “What would Charlotte do?” That question has probably been asked almost daily for the 95 years that have followed. It is a question often raised by the Charlotte Mason community today.

The fact is that we live in a new millennium. We have the Internet; we have cell phones and computers; we have Netflix and tablets. Science has advanced, educational research has continued, and the world seems to spin faster every day. What would Charlotte Mason have done with all this? If she were alive today, what would she do differently? Which parts of her curriculum or method would she change? What new things would she adopt? What old things would she drop?

To answer this question, we must first identify what a Charlotte Mason education actually is. Is it a means for developing an educational method, or is it itself an educational method? In other words, is it fundamentally a set of criteria (a methodology), or is it fundamentally a set of guidelines (a method)? This is a vital question for the Charlotte Mason community today.

Some say that Mason was firmly embedded in the classical tradition of education, and as such, her fundamental orientation was to elucidate that tradition, rather than to firmly break from it. If that is the case, then it would seem that a Charlotte Mason educator today would be more committed to the classical tradition than to Mason’s own unique contributions (if any are even recognized to be unique). To be “authentically CM” would mean to maintain primary allegiance to that classical tradition, and to embrace whatever is found to be most true to that kind of education, whether new or old.

Martin Cothran of Memoria Press expresses this viewpoint perhaps better than anyone else. For Cothran, a true Charlotte Mason educator would seek to subordinate and merge her method into a single “classical vision”:

Those in Christian education circles talk about the ‘Charlotte Mason Method,’ … The reason we do this, I think, is that we are all living in the wake of the Great Education Shipwreck, which occurred roughly in the early twentieth century. The coherent vision of what education was for—the intellectual, moral, and cultural formation of human beings—was lost…

What we have been left with is the flotsam of sometimes confused but always fragmented educational approaches, each floating around, disconnected from the other pieces of the wreck, and each, in ignorance of the ship from which they all came, thinking that they constitute the whole ship…

Charlotte Mason got the ‘Charlotte Mason Method’ from classical education…

They only now seem at odds with each other because they have been disconnected from the larger and more ordered system of which they were all once a part…

We just think they need to be brought together and put back in their proper place in the original classical vision of education. (Cothran, 2017)

Andrew Kern of the CiRCE Institute expresses a similar view:

… when you look at the essence of classical education as it persists through the ages, Charlotte Mason sings the same song, dreams the same dream, and refined the same practices rooted in human nature as Image, temple, and person. (Kern, 2018)

For someone holding this paradigm, the answer to the question, “What would Charlotte do?” is found in the classical tradition. If Mason were alive today, she would emphasize classical languages more. She would make more use of the Socratic method. She would attempt to get her methods adopted by contemporary classical schools. She would promote schools that are “Classical and CM.”

On the other hand, some say that Mason was squarely embedded in an ongoing process of reform, and as such, her fundamental orientation was to embrace whatever is new, rather than to point to timeless and unchanging truths. If that is the case, then it would seem that a Charlotte Mason educator today would be more committed to the latest discoveries of science and theology than to Mason’s own (perhaps dated) conclusions. To be authentically CM would mean to maintain primary allegiance to contemporary thought, and to embrace whatever is found to be most true to the latest research.

For someone holding this paradigm, the answer to the question, “What would Charlotte do?” is found in the latest academic research. She would update her model of narration. She would rely more on manipulatives and conceptual subitizing in math instruction. She would revise and adjust based on neuroimaging.

If we allow Mason to speak for herself, however, we find that neither paradigm reflects Mason’s own self-understanding. The inescapable conclusion from the complete set of her writings is that she believed that she had discovered a method and not merely a methodology. She believed that she had discovered a set of timeless and unchanging truths from which she could derive a stable and reliable set of principles and practices. And those principles and practices do not change whether one looks more closely at the past (to classical ideas) or at the present (to the latest scientific discoveries).

Mason asserted the uniqueness and finality of her philosophy with surprising clarity and confidence in a 1904 letter to Henrietta Franklin:

I think you have already brought before our Committee my strong sense that the P.N.E.U. is rather wasting its opportunites. It is practically a Society for providing desultory lectures to parents of a more or less instructive and stimulating character.

It might be, and was in my original intention, a College of Parents existing to study and propagate a philosophy of education—I believe the only sufficient and efficient philosophy of education which exists. (Mason, 1904, p. 1)

Mason grounded this remarkable assertion not in her own genius or talent, but rather in her perception of divine agency:

The thing we hold amongst us is too great to be lost and I believe, is God-given. There is no other school of educational thought which even professes to have any adequate philosophy of education. Indefinitness of aim and faulty methods make shipwreck of education on all hands. (Mason, 1904, p. 3)

Remarkably, both Cothran and Mason speak of a “shipwreck” of education. According to Cothran, the shipwreck occurs when Mason’s method is separated from the classical tradition. According to Mason it is just the opposite: the shipwreck occurs when her method is merged in with the rest.

Mason did not conceal her views on this matter. In 1996, the Ambleside Oral History Group interviewed Joan Fitch (b. 1911), a former student of the House of Education. Fitch observed that Mason held her method to be God-given and immutable:

Everyone respected her and her reputation, which was national in a way and the Board of Education, as it was then, wrote to her, I learnt afterwards, several times, beseeching her to bring the College into the National scheme but this would have meant dropping one or two of her favourite ideas and she wouldn’t give way to anybody. She felt, I think, that her ideas had been straight from heaven and she mustn’t interfere with them (but) carry them out to the best of her ability. (Fitch, 1996, p. 3)

Contrary to the presuppositions of Cothran and Kern, Mason anchored her views in her personal experience and not in the classical tradition:

I. Did she formulate her ideas solely from her own observations or had she studied others—earlier educationalists?

R. She had done, I would say, but I would say the personal experience won. But at the same time, she was well-read and quite widely read in the classics and through history. (Fitch, 1996, p. 10)

Fitch recounts again and again Mason’s absolute refusal to change anything about her method:

But it was interesting that Charlotte, as an individual, made an impression and was visited several times by quite .. authorities from the Board of Education and she impressed them but she wouldn’t give an inch, she was really very—a very dedicated person to watch. She felt it had been given her and she felt it was up to her to pass on. (Fitch, 1996, p. 10)

Charlotte firmly insisted on keeping herself apart and was adamant to anyone who tried to persuade her to join the National scheme because she knew that she would object to quite a bit of it. (Fitch, 1996, p. 5)

Interestingly, other educational camps were willing to modify their methods here and there to comply with national standards. But Mason absolutely refused:

Because although Charlotte Mason’s ideas and theories roused a great deal of general interest and she was paid visits periodically at one time by deputations by the then Board of Education who were anxious to persuade her to change some of her theories to tie in more closely with the theory and practice of the day solely in order that the training could be recognised. The Froebel authorities had managed to do this and Froebel teachers were recognised teachers and could teach in local schools as well as in their own. Charlotte Mason was adamant and she would not give at all and reluctantly she was refused recognition, they must take all or nothing; which was I think by the time it got to my day definitely a pity because our actual opportunities then were very restricted after we left. (Fitch, 1988, p. 7)

As might be expected, then, we find astonishing consistency in the details of Mason’s method across long spans of time. Consider just two examples: mathematics and Bible lessons.

In 1911, Irene Stephens wrote “The Teaching of Mathematics to Young Children” “at the request of the Board of Education and under Miss Mason’s supervision.” This text became the backbone of math instruction in the PNEU for at least 50 years. The paper was reworded by Stephens for The Parents’ Review in 1929, then renamed “Number. ‘A Figure and a Step Onward.’” This article was later published as a standalone booklet, and was still being sold by the PNEU as late as 1962 (PNEU, 1962, p. 6). In defiance of a half-century of academic research in the instruction of mathematics, the Charlotte Mason community still turned to Irene Stephens.

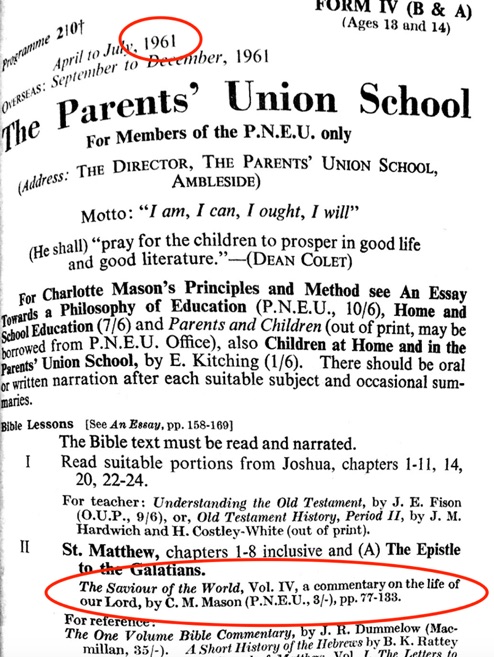

We see a similar enduring consistency in Bible lessons. Charlotte Mason published the first volume of The Saviour of the World in 1908, and the volumes were in constant use in the PNEU for the next 50 years. It was not until 1961 that we find the last PNEU programme to assign a range of pages in Charlotte Mason’s The Saviour of the World.

We see a similar enduring consistency in Bible lessons. Charlotte Mason published the first volume of The Saviour of the World in 1908, and the volumes were in constant use in the PNEU for the next 50 years. It was not until 1961 that we find the last PNEU programme to assign a range of pages in Charlotte Mason’s The Saviour of the World.

Charlotte Mason’s survivors maintained this tradition because they believed in the enduring value of the method itself (not the methodology). In 1933, Elsie Kitching wrote to Henrietta Franklin:

We believe that what will ultimately survive all changes and chances will be [Charlotte Mason’s] philosophy, and our danger at the present moment is the limiting of it to fit current conditions of thought and practice of life generally, that of “schooling” in particular. (Kitching, 1933, p. 5)

As late as 1948, this enduring quality was recognized by a reader of Mason’s writing:

An able lecturer in an Emergency Training College wrote recently, ‘There is a permanent quality in all Miss Mason’s work, a sense of urgency, as if writing for the present moment, that I do not find elsewhere. One remembers the famous comment “Not for an age but for all time.” Miss Mason’s writing has, if it is not impertinent of me to say so, that quality.’ (PNEU, 1948, p. 486)

At this point it is important to emphasize that I am talking about the method of education, not the range of subjects which may be studied. While Mason included some classics in her curriculum, that does not make her classical. Similarly, she could continually add more fields of study to the science curriculum without surrendering her commitment to certain unchanging truths. So a modern Charlotte Mason educator can study quarks and Java even though neither are found in any of the historical PNEU programmes.

What were the timeless and unchanging truths that Mason believed she discovered? That children are born persons. (It is important to note that her primary frame of reference for this principle was the child’s estate as articulated by Christ. It is primarily a theological commitment, rather than a physiological one.) That knowledge is formed through narration. That the Holy Spirit is the supreme educator. And that we learn through the real world, and not through artificial environments.

What if classical education casts doubt on any of these principles? Do we on that basis say, “if [Mason] were alive today, she might choose slightly different points to emphasize” (Glass, 2014, p. 12)? Do we follow contemporary classical educators who say that Charlotte Mason educators should emphasize virtue, or classical languages, or the Socractic method?

Charlotte Mason knew about all of these classical methods and she rejected them; she built on a different foundation. When an artist was asked to compose a Certificate for House of Education graduates, the artist drew a picture where “the rise upward through the education of the children’s best possibilities, landed them in a heaven of highest culture that was fitly typified by a beautiful Greek temple.” This picture was rejected because “it lacked that acknowledgment of Christian inspiration, which is so essentially the keynote and foundation stone of the House of Education.” New artwork was requested which better reflected “the scheme of the House of Education, [where] the mother is the guiding and controlling force of the children’s fullest life” (PNEU, 1896, p. 476).

Mason’s stance here reminds me of her Saviour’s encounter with the Greeks in John 12. Jesus and His disciples did not turn to the Greeks to understand the path of virtue or the way to knowledge. Instead, the Greeks came to Jesus: “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” And Jesus answered them “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified” (John 12:21, 23, ESV, 2016). It was on this rock, the glorified Son of Man, that Mason built her House of Education.

And what if contemporary scientific research were to cast doubt on any of these principles? What if science were to show that children are incomplete persons after all? Or that narration isn’t really what forms knowledge? Or that understanding is developed more rapidly from artificially developed environments and manipulatives than from the real world? What if the latest biblical scholarship were to determine that the Holy Spirit does not, in fact, assist parents in a grammar lesson?

What then? Does that mean that the authentic Charlotte Mason educator would follow the “methodology” and abandon these discredited principles in the spirit of following the CM way? Or would the research rather cast doubt on the CM method as a whole? Wouldn’t the research rather lead the authentic student to conclude that Mason got it wrong, and that it was time for a new reformer to articulate a new method and a new way, this time in harmony with what science and theology are really saying?

When it comes to the question of math, artificial manipulatives were available in Mason’s day. She evaluated them and found them lacking:

Therefore I incline to think that an elaborate system of staves, cubes, etc., instead of tens, hundreds, thousands, errs by embarrassing the child’s mind with too much teaching, and by making the illustration occupy a more prominent place than the thing illustrated. (Mason, 1989a, p. 262)

Mason pointed to special and general revelation, and in harmony with her seventh principle, she said that children should learn in the real world, from real objects, and not in an artificial child-friendly environment. But if research shows that she was wrong, and that Montessori was right, then let us transfer our allegiance to the dottoressa. That would be better than claiming that the Charlotte Mason way is to import ideas from Montessori.

Scientists may conclude that nature study is not really the right way to prepare a child for life. Science may show that the Holy Spirit is not to be found in the classroom. Science may show that living books are a myth and that no book is really alive. But if those things happen, then science has proven that Charlotte Mason was wrong. And the best thing to do would be to leave her work in the Armitt Museum and move on to something that is true.

But science has tried to prove many things. For example, it has tried to prove that a man who was dead for three days cannot rise to life. The Greek philosophers couldn’t accept it either: “when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked” (Acts 17:32, ESV, 2016). But science and philosophy meet their match when they face the Person who created both. And that is the same Person who said, “Suffer the little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 19:14, KJV, 2009). Those words are a rock upon which one may build a theory of education that can withstand the winds of change.

What would Charlotte do? When we understand her own paradigm, it is an easy question to answer. She would do what she did.

References

Cothran, M. (2017). Letter from the editor: Winter 2017. Louisville: Memoria Press. Accessed March 23, 2018.

ESV. (2016). The Holy Bible: English standard version. Wheaton: Standard Bible Society.

Fitch, J. (1988). Transcript of interview. Ambleside: Ambleside Oral History Group. Accessed March 23, 2018.

Fitch, J. (1996). Transcript of interview. Ambleside: Ambleside Oral History Group. Accessed March 23, 2018.

Glass, K. (2014). Consider this: Charlotte Mason and the classical tradition. Publisher: Author.

Kern, A. (2018). 6 Reasons Why Charlotte Mason Was Part of the Classical Tradition. Concord: CiRCE Institute. Accessed March 23, 2018.

Kitching, E. (1933). Letter to Henrietta Franklin. Box CM42, file cmc266, document 12p5cmc266. Armitt Museum, Ambleside.

KJV. (2009). The Holy Bible: King James version. Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc.

Mason, C. (1904). Letter to Henrietta Franklin. Box CM42, file cmc266, documents 116p3cmc266 & 116p5cmc266. Armitt Museum, Ambleside.

Mason, C. (1989a). Home education. Quarryville: Charlotte Mason Research & Supply.

PNEU. (1896). Our work. In The Parents’ Review, volume 7 (pp. 474-476). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

PNEU. (1948). Report on the Parents’ Union School, June, 1947-1948. In The Parents’ Review, volume 59 (pp. 485-486). London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

PNEU. (1962). Preparatory programme 12. London: Parents’ National Educational Union.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

14 Replies to “What Would Charlotte Do?”

Thought provoking!

Thoughtful, thorough, gracious response to differing opinions on Mason’s work, especially as it relates to math.

Celeste,

Thank you for the kind words. I am glad it came across as gracious, and I hope you found it helpful.

Blessings,

Art

Very interesting. I did not know that Charlotte Mason had spoken against number rods and cubing. I agree, that one should understand what someone actually thought before assuming what he or she would think of a new (or recycled) practice. I believe that Charlotte Mason was used by God, but I’m not a follower of hers in the sense of one who agrees with everything she taught. In learning from her, just as I learn from Montessori, I give as much consideration as I can to everything I read from them, as I consider them to be extremely intelligent, skilled, and successful, but ultimately I am the sort (INTJ) that will use my own reason to evaluate each word they say, and sometimes I disagree. Siegfried Engelmann is another educator that I respect. His method he calls “Direct Instruction”, and like Montessori and Mason, it is both innovative and in debt to the work of dead men. “Direct Instruction”, taken as a whole, is completely at odds with everything that Mason or Montessori proposed, however, when you look at [what I consider to be] the core, with rules about the logic of communicating a new concept, I believe that wherever there is a place for direct teaching (such as in mathematics) in other methods, there is room the insights of Engelmann’s rules. This is not to say that Montessori or Mason or Engelmann would approve of taking pieces from their methods or adding those pieces with other methods. It’s also not to say that this is a “better” way than sticking with just one proven method, as in practice most of us would fail to achieve the goals we would set out should we try to innovate. We are not all born to be innovators in that sense, thankfully, as the world and the library of ideas would be awfully chaotic.

When I was in the crash course for Montessori’s Casa dei Bambini, before I took the course for the “elementary” level, I remember wondering why it was necessary to use specialized objects rather than normal objects from everyday life. I still feel that is a worthy goal. Now, though, I believe I understand better why Montessori chose use, for instance, planar figures cut from metal: she is trying to teach abstract concepts from mathematics, and she is trying to actually represent those abstract concepts as much as possible with physical representations, so that the child can see with the eye and more easily understand with the mind.

I also remember some topics in the elementary training, such as cubing and finding a square root manually, seemed… not essential knowledge, especially in elementary education. I thought, “I would probably spend my time teaching them something else more important.” And I can’t say I think differently about that at the today, although it’s worth noting that Montessori did not include those things because they were, per se, important things to know. She included them because the reasoning mind of the child found them fascinating, and it gave something for the muscle of their reason to work on and increase in skill. I must disagree with the quoted words from Mason, that these concepts are confusing to children; confusion only comes from presenting them in an inappropriate way. The same can be said about teaching young elementary students grammar and sentence analysis, or four-year-olds how to read, in my opinion. Regarding number rods, I don’t know enough about Mason’s alternative approach to judge her dismissal of them.

I agree with this article, that it’s not profitable, true, or fair to misrepresent someone’s philosophy. I have to be careful of that with Mason, as my knowledge of her vast methodology is yet limited. I have written here with the assumption that those who are not purists are welcome to comment, but if I was wrong in that assumption, my apologies.

I do think it is immensely worth the time, for those so inclined, to not merely sprint through the forest of a philosophy or school of thought, whether pedagogical or otherwise, but to saunter through, to hear what they have to say, to hear their reasonings, to consider arguments in favour and against their propositions, and to compare them with our own personal experiences. Part of what made the greatest educators of the past the greatest was not only that they had sifted the river of man’s past thoughts, but that they actually spent time with kids!

Pat,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment. I appreciate that while you take the time to study and make your own decisions, you are careful to respect the integrity of the work of great thinkers like Charlotte Mason and Maria Montessori.

I think you captured the heart of my post when you wrote:

I agree, that one should understand what someone actually thought before assuming what he or she would think of a new (or recycled) practice… I agree with this article, that it’s not profitable, true, or fair to misrepresent someone’s philosophy.

Blessings to you as you continue studying, reflecting, and teaching.

Respectfully,

Art

Art, great article! Thanks. I was hoping you might speak to your understanding of Charlotte’s in Volume 2 on pages 45-46. “We must feel our way to some test by which we can discern a working psychology for our own age; for, like all science, psychology is progressive. What worked even fifty years ago will not work to-day, and what fulfils our needs to-day will not serve fifty years hence; there is no last word to be said upon education; it evolves with the evolution of the race.” This certainly seems, on the face of it, to say that she believed that some things would change and grow. Can you elucidate for us?

Yes. Please see this article by Lisa Osika: “What Worked Fifty Years Ago.”

Thank you for this post, Art!

It was, as usual, well written, informative and thought provoking. It is so important for us in this new era of using the Mason method not to lump her in with other methods. I appreciate your concern to present the truth of what she said about her method here on CMP.

-Mary

Thank you for the encouraging feedback!

This. “She built on a different foundation.” Thank you, Art, for articulating so well what I cannot (yet).

Thank you so much, Mr. Middlekauff. Informative and interesting, as always.

Why would a science book published a hundred years ago be more advisable than Jay Wile’s new Science series? And how do you feel about those boxed experiment kits? Jay Wile seems somewhat living, but the Eyes and No Eyes Series still seems somewhat more favorable. I was just curious what your thoughts were. I am guessing that doing a curriculum centered on experiments would by default take up time that could be spent outdoors. But do you think his books could be used starting in Form 2? Or not at all?

Dear Liz,

Thank you for raising this interesting question. I would like to clarify a few points, just to make sure there is no misunderstanding. The intention of this article is not to claim that there exists a static list of living books that must be used in this generation to be faithful to the Charlotte Mason method. I argue that Miss Mason advanced a set of principles that are timeless, but I grant that certain details of implementation (such as book lists) may vary by generation and geography.

I am not familiar with Jay Wile’s new science series, so I cannot say how it compares to a science book from a hundred years go. I would prefer, anyway, to answer the question in the words of Charlotte Mason herself:

… which are the right books?—a point upon which I should not wish to play Sir Oracle. The ‘hundred best books for the schoolroom’ may be put down on a list, but not by me. I venture to propose one or two principles in the matter of school-books, and shall leave the far more difficult part, the application of those principles, to the reader. (School Education, p. 177)

I will argue without hesitation in favor of Mason’s philosophy and theology of living books; however, I am not prepared at this time to argue over specific science book titles. Armed with the principles, the reader should be able to make the right decision.

Please note also that Mason did encourage the use of experiments in science education. For a balanced treatment of this, please see Richele Baburina’s article on this topic.

Blessings,

Art

Thanks so much! That really makes a lot of sense.