Latin — the elegant Tongue

Editor’s Note

by Angela Reed

The defense of Latin is a tradition almost as old as the language itself. In the modern era, one can find many passionate defenders of lingua Latina in homeschool discussion forums or in Facebook groups, where they swiftly emerge out of the digital woodwork in response to posts like the following:

When I told my husband that I was planning to do Latin this year with our 4th grader, he wasn’t pleased. He told me that Latin is a dead language and is basically a waste of time. I tried looking for some explanation as to why this subject is scheduled but found none. Can anyone give me an answer here?

So, sell me on Latin—or don’t. Why do we need to teach our students Latin? I guess that I’m looking for both utilitarian and “living” reasons. It seems that everyone says Latin is required. But required for what?

Talk to me about Latin. Why is it worth adding as a subject? How has it helped your children? We do a foreign language because we’re bilingual, but since Latin is a dead language I have never understood why it’s worth learning.

Someone please convince me why we need to do Latin. I’ve thought about it for years, and didn’t do it with my older kids. I haven’t yet come across a reason compelling enough for me. We have limited time to study and learn all the things, so tell me your most persuasive, CM-oriented, meaningful and powerful reasons to study Latin.[1]

At the heart of each of these queries is a simple why? Why study Latin? If you have ever pondered this question or encountered the usual objections—that Latin study is unnecessary with so many translations available; that it is a sentimental pursuit and a throwback to the so-called “good old days” of education; or that it is a grind better left in the Victorian Age—well, you would not be alone in your thinking. In fact, you would hardly be the first to pause at these objections and seriously weigh them against the benefits for your children’s education.

Latin has endured its share of detractors throughout the centuries, most of whom were preoccupied—as we often are today—with utility. Of what use is it? A very brief history of the language demonstrates how resiliently it has wrestled with utilitarian demands. In Roman times, Latin was spoken all over the empire and the ancients saw its study as an indispensable part of Roman education, for recte loquendi scientiam et poetarum enarratione,[2] that is, for developing refined skill in speaking and interpreting the literature of the poets. Such rhetorical training was practical and necessary for young men on track to political leadership. With the fall of the Roman empire, this literary Latin lay preserved in ancient manuscripts but lived on in the speech and education of the monastics. These medieval men and women of the Church protected collections of classical and sacred writings for hundreds of years, carefully copying them letter by letter for posterity’s sake. Meanwhile among the peoples of the former empire, vulgar (i.e. colloquial) Latin slowly evolved into various regional dialects, precursors of modern Romance languages like French, Italian, and Portuguese. As the Middle Ages yielded to the spirit of the Renaissance, scholars, educators, and even the papacy resurrected the classical Latin of Cicero. In fulfilling the stylistic impulse of the age, this movement set vulgar Latin to the side; but in return, it gave to Western civilization a common language for the sharing of scholastic and scientific knowledge.

Latin would continue to flex and adapt in response to needs birthed by events of the Modern Era: the American colonies would incline to ancient Rome for philosophical and governmental organization of their fledgling republic and for the cultivation of civic and moral virtue in their citizenry. Latin, alongside Greek, would maintain a standard of educational excellence for higher education in Europe and the United States—at least for a while. Amid wars, revolutions, and the machinery of industry, the classical curriculum began to feel the squeeze of pragmatism as it competed with practical subjects for lesson time. Greek would soon be on the chopping block; Latin was feared next in line. To avoid cancellation, progressive educators fought for reform, insisting that living methods, such as those used for modern languages, be tried and applied to classical languages.

At this critical juncture, aptly named a “crisis in Classics,”[3] Miss Mason lent her efforts to the cause of the progressives. In 1912, she addressed the great Classics debate publicly and extensively in a series of letters to The Times newspaper, published later in pamphlet form as “The Basis of National Strength.”[4] Therein, she directly challenged the argument that one should “give a boy professional instruction … and strike out from his curriculum Greek or geography, or whatever is not of utilitarian value.”[5] To the recurring “expedient of dropping Greek to make room for other things” she replied with a firm, “No.”[6] The classical languages must be retained, she argued, but the methods had to change. What method, then, would serve as the solution? By 1919, after nearly a lifetime of working out her philosophy of education, she landed on her answer: narration, which brought an “hitherto unused power of concentrated attention” to bear in language study. When she implemented this method for Latin at the House of Education, Miss Mason found it both efficient and effective, enabling students to pursue Latin study within the feast of a liberal education.[7]

With the end of World War I, the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge finally dropped Greek as an entrance requirement for undergraduate students. This change, part of a major institutional restructuring of higher education, reflected a cultural shift that would have far-reaching consequences thereafter for the teaching of Classics and Latin in schools. After Mason’s death in 1923, the PNEU continued to advance her vision under the banner of “A Liberal Education for All.” But could the study of Latin—long part of the tradition of liberal education—truly be made accessible for all?

The enduring presence of Latin in the PNEU Programmes after Mason’s death and beyond testifies to the PNEU’s commitment to this vision. So too does the publication and immediate adoption in 1927 of a new beginning Latin text developed on the method of narration. This text, authored by Miss M.C. Gardner, Lecturer in Latin at the House of Education in Ambleside, became the PNEU’s primary recommendation for Latin instruction and preparation for the reading of Latin literature in the upper forms. There is still much to be learned about what the PNEU advised for Latin during the 1940s and ’50s—a time which saw the discontinuation of Latin in many schools. However, when Oxford and Cambridge officially dropped the Latin requirement for college entrance in 1960, the PNEU withstood the tide. A 1961 book review, published in the Parents’ Review, affirmed their stance in brief: “Some time ago there was a prolonged correspondence in The Times on ‘the use of Latin in schools,’ which made one thankful that this basic language is in no danger of being removed from P.U.S Programmes.”[8]

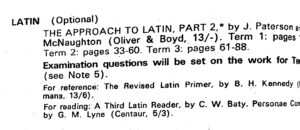

Latin would continue to hold a place in the Programmes through the next two decades.[9] But in 1970 a small but significant change appeared: for the first time Latin was listed as “(Optional).”[10] It was not the only subject to suffer a demotion, as German, French and even Music Appreciation were made optional during the 1970s. And yet the PNEU’s confidence in Latin remained strong, as attested by an article that appeared in the PNEU Journal in 1973 entitled, “Latin—the elegant Tongue.”

With this article we come round once again to the time-honored tradition of defending Latin. But unlike so many defenses today, this one does not regale the reader with linguistic trivia or try to impress with standardized test scores and college entrance statistics. Rather, it assumes the reader already recognizes the value embedded in Latin while it pokes fun at the historical situation of the Romans—that “bellicose” people with a “knack for organization”[11]—and the endurance of their language, inextricably bound up (as it ever will be) with Western civilization in all its strange and glorious history. So while critics may scoff—as a friend of ours once did when he declared, “Latin? What does that relic have to do with Charlotte Mason?”[12]—we present you with a humorous, not-quite-apologetic take on how truly relevant Latin is especially in light of all the “appalling similarities” to be found between the old Roman world and ours. We hope that the author convinces you, as we are convinced, that Latin cannot truly be called dead “as long as there are people who learn and use it.”[13]

Latin—the elegant Tongue

By Igor Gazdik

The PNEU Journal, 1973, pp. 70–71

In our time of automatic factories, long-distance communications, astronautics, computers, and effective education, one may ask whether the study of Latin is still justified. There are a number of arguments discouraging further studies of Latin. It is said to be a dead language, previously spoken by people living under entirely different social, cultural, and economic conditions. A language which was geographically limited and can no longer be creative. However, no language is completely dead as long as there are people who learn and use it.

But why do they? Have the Latin, and the present worlds anything in common? The answer must be sought in the origin of the language and the history of its users.

The only interesting thing about a handful of herdsmen, once living in the estuary of the Tiber was that they were bellicose while having a knack for organization. Thus, they fought their neighbours, even the highly civilized Etruscans, and expanded. After having founded their city, Rome, the expansion went on beyond the limits of Latium, as their area was called. They conquered the Greeks and their possessions went farther into Asia and Africa and finally colonised large parts of the three continents.

However, their expansion was not only a barbarous drive after new colonies. The Romans spread their influence, language, religion, and culture, while respecting their vassals. The Romans learned from them, adopted and adapted their culture and their gods. Remember, that the Greeks knew everything at that time. They systemized science and philosophy, medicine, arts, and carried out research for the sake of knowledge alone, founded cities, trade relations, and legislation. But they had to give up for the Roman strategy and art of organization. The Romans, in turn, absorbed the Greek culture and further developed it. Thanks to this, monuments of architecture, sculpture, and engineering survived up to our era. Successful conquests abroad and events at home gave rise to rich and stylish literature and rhetorics, and required effective legislation.

Comparing this brief outline to our world, we find appalling similarities. As before, there is a strive, although less elegant, to subjugate the world under one, or a few, ruling centres. Hand in hand with this go experiments with introducing very few universal languages. The world grows smaller with the development of science and a need for unification is felt by everybody, at the same time as effective organization is appreciated in all walks of life. Moreover, Latin books, or, for instance, the inscriptions on the walls of Pompeii disclose deeply moving common traces in human character and sentiments which persist until today, only in different disguise and with different cast. The continuity in the development of mankind provides a safe base for learning from the virtues and the mishaps of the past. The elegant Latin language is an important link in the chain of historical development.

The influence of the language did not follow the decline of the Roman Empire. While, on the one hand, some Latin dialects instituted themselves as separate languages, ranging from Portuguese to Romanian, the classical Latin continued to be used, in a simplified form, by the Church and by the medieval scholars. Thus, it is not only historical studies which require a sound knowledge of Latin nowadays. Everybody studying philology, botany, zoology, biology, medicine, or philosophy, everybody striving after profound education in humanities, and everybody wishing to acquire a good writing or rhetoric style, finds the knowledge of Latin to be indispensable.

Finally, to meet the demands of the modern world, no matter whether in science, sports, or law, presupposes the use of at least a limited Latin vocabulary. The opening paragraph of this article may serve as an example. So, the ‘to be or not to be’ of Latin in the curricula of schools can unhesitatingly be answered in affirmative.

Angela Reed has been a student of lingua Latina and classical civilization for over twenty-five years. She started on this path in high school when she took her first Latin class and, for extra credit, joined the Latin club. She has been enthusiastically carrying a classical torch ever since. When she first encountered the educational philosophy of Charlotte Mason, it was not long before she began to study how Latin fit within it. This research led to some surprising insights, experimentation in the classroom, and a new direction for her teaching: Living Latin Lessons—live online classes offering a Charlotte Mason approach to Latin. She and her husband live in Florida and share a life of books, music, and outdoor adventures with their five children.

Editor’s Note © 2024 Angela Miller Reed

Editor’s Note: The formatting of the above article was optimized for online viewing. To access a version which is formatted more similarly to the original, and which includes the original page numbers, please click here.

Endnotes for the Editor’s Note

[1] These excerpts are from actual social media posts which have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

[2] Quintilian 1.1.1

[3] See Stray, C. (1992). The Living Word: W.H.D. Rouse and the Crisis of Classics in Edwardian England for a thorough treatment of this subject. The period from the 1870s to the 1920s “could be claimed to be the last major crisis of classical studies in England: a crisis in which Classics was detached from its central place in English high culture.” (Preface, p. iv)

[4] Mason, C. M. (1989). A Philosophy of Education, pp. 300–342.

[5] Ibid., p. 302.

[6] Ibid., p. 309.

[7] Ibid., p. 213. See also “Editor’s Note” by Reed, A. (2021) “The Teaching of Latin.”

[8] Parents’ Review, 1961, p.144

[9] The PNEU School, Programme 87 (1977–78) contains the latest evidence of Latin’s presence in the Programmes that I have yet found.

[10] The PNEU School, Programme 237 (April to July, 1970).

[11] Gazdik, p. 70.

[12] Middlekauff, A. [@charlottemasonpoetry]. (2022, August 11). Winnie Ille Pu [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/ChHeTyHukwB/

[13] Gazdik, p. 70.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music