The CMP Review — Week of April 15

April 15, 2024

“No two children are alike, no two require the same treatment or method. It is here that we fall back with relief to the stableness of Miss Mason’s teaching. Here are no black and white rules for the regulation of all children, but rather a strong framework of all-embracing principles which will prove a secure foundation for the buildings of experience.” (Laurence, Playroom Leaflet, PR48, p. 714)

@tessakeath

April 16, 2024

Picture study is one of the iconic elements of the Charlotte Mason method. Its appeal has spread beyond the school room and into conference presentations and even sermons. Part of its appeal is its simplicity: look at a picture and describe it. Anyone can do it.

However, Charlotte Mason also wrote that “we recognise steady, regular growth with no transition stage.” The gradually progressive nature of her applied philosophy is subtle but evident in the PNEU programmes from Forms I to VI. Is this steady, regular growth manifested in picture study as well?

If anyone would know, it’s Mary Gillies. After studying at Charlotte Mason’s House of Education, she went on to teach for 35 years at the celebrated Burgess Hill PNEU School — a school which taught girls across all 6 forms. And she loved picture study.

Today we continue our series of articles on picture study with a 1931 piece by Mary Gillies which shows the steady, regular growth in this subject from Forms I to VI — and she illustrates her points with student examples. Her article offers much that can be used and applied today, and now you can find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

April 17, 2024

Little is known about Emily Brontë, and there’s certainly no evidence of the type of relationship portrayed in the recent dramatic film by Frances O’Connor.*

One thing we do know about Emily is that she retained an unabashed authenticity—and this the movie captures incredibly well.

In her own words,

Let me be false in others’ eyes,

If faithful in my own.

@rbaburina

*Rated R

April 18, 2024

A contemporary resource defines discipling as “deliberately doing spiritual good to someone so that he or she will be more like Christ.” It seems to imply that there is another kind of good we can do to someone, to help them towards some other good end. Perhaps the label we give to that kind of service is education.

I am currently reading John Ruskin’s Mornings in Florence. But I didn’t start with Chapter 4, “The Vaulted Book,” which Charlotte Mason quotes so extensively in her works. Rather, I started with Chapter 1. And I’m glad I did.

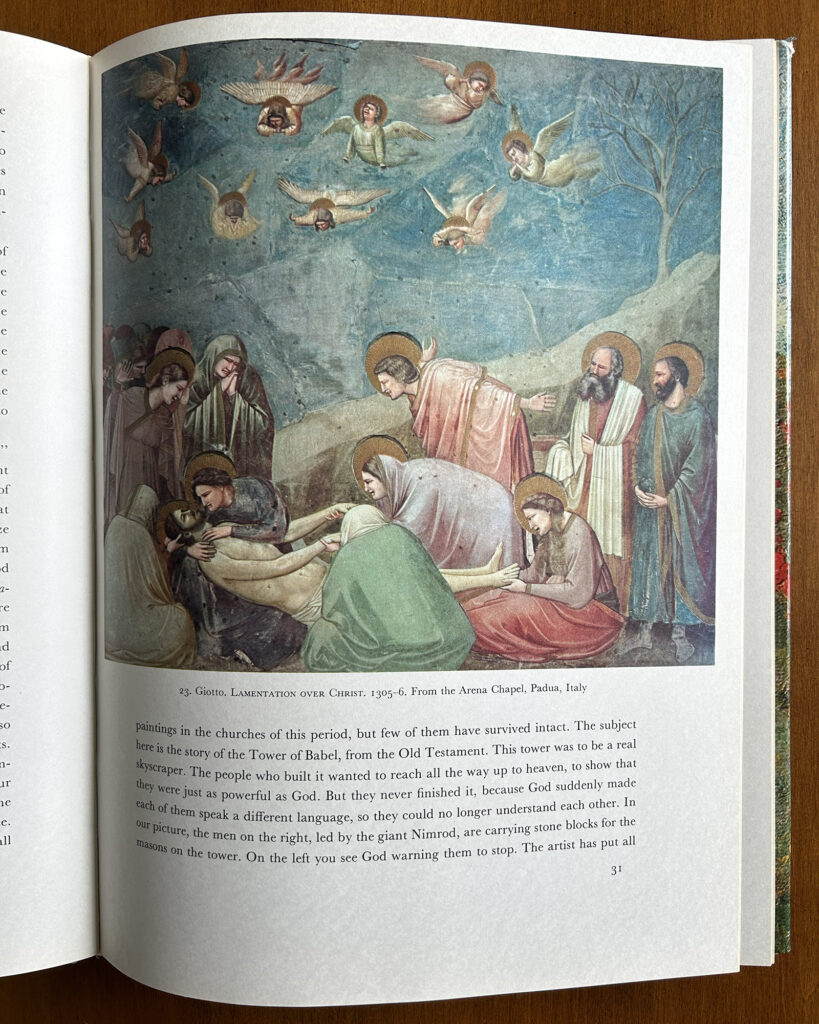

In the second chapter, Ruskin presents his interpretation of Giotto (1267–1337) and the impact of his life and work. “Domestic and monastic,” writes Ruskin. “Giotto was the first of Italians—the first of Christians—who equally knew the virtue of both lives; and who was able to show it in the sight of men of all ranks.” According to Ruskin, Giotto showed the world that “household wisdom, labor of love, toil upon earth according to the law of Heaven … are reconcilable, in one code of glory … with the repose of folded hands that wait Heaven’s time.”

Benjamin Bernier, in his 2009 book Education for the Kingdom, asserts that Charlotte Mason’s philosophy of education is at its core a theology of discipleship. He refers to her work as an “educational vision of discipleship.” Household wisdom, labor of love, and toil upon the earth are spiritual activities, as much under the instruction of the Spirit of God as lessons in Bible and theology.

Ruskin said that Giotto “makes the simplest household duties sacred, and the highest religious passions serviceable and just.” Isn’t that just what Charlotte Mason does? Hasn’t she shown us that the call to educate our children is a most spiritual call? That grammar, drill, chores, and math all take their place in unfolding to us the knowledge of God?

Perhaps Mason has shown us that the contemporary definition of discipling does indeed describe what we do. Not because we’ve expanded our definition of discipleship, but because we’ve expanded our definition of what is spiritual.

@artmiddlekauff

April 19, 2024

The lowly dandelion. Jubilant sign of spring. Model of resilience and strength.

@antonella.f.greco

April 20, 2024

I came across this WB Yeats poetry collection at a recent book sale, and as he is our poet this term, it was well-timed and I couldn’t pass it up. I covered the dust jacket in mylar so it can continue to protect the book for years to come.

Do you have any books you stumbled across at what felt like perfect timing?

@tessakeath

April 21, 2024

I will never forget the first time I entered the hall of the seven virtues in the Uffizi Gallery. I looked intently at the first painting, and then the second. “Paintings,” I thought. Another, and another. Until finally I reached the end of the hall, and then I gasped. I could not simply say to myself, “Painting.” For I was standing before something that was more than a painting.

“Everybody else’s Fortitudes announce themselves clearly and proudly,” writes John Ruskin. “They have tower-like shields, and lion-like helmets—and stand firm astride on their legs,—and are confidently ready for all comers.”

Not so the Fortitude of Sandro Botticelli. “Botticelli’s Fortitude is no match, it may be, for any that are coming. Worn, somewhat; and not a little weary, instead of standing ready for all comers, she is sitting,—apparently in reverie, her fingers playing restlessly and idly—nay, I think—even nervously, about the hilt of her sword. For her battle is not to begin to-day; nor did it begin yesterday. Many a morn and eve have passed since it began—and now—is this to be the ending day of it? And if this—by what manner of end?”

Charlotte Mason read these words of John Ruskin in Mornings in Florence. She alluded to them in Ourselves Book II in her chapter on Fortitude.

When speaking of humility, Mason quoted William Law: “There never was nor ever will be, but one humility in the whole world, and that is the one humility of Christ.” Perhaps there is only one fortitude also. When Mason wrote of the fortitude of Christ, she cited Ruskin again. And she cited Botticelli again. And I know why. Because it is really more than a painting. Read or listen to Mason’s poem on the fortitude of Christ here.

@artmiddlekauff