The Story of Scale How Meditations

In 1861, a nineteen-year-old was starting her first full-time job. She had just moved and was by all accounts feeling overwhelmed by her new set of responsibilities. She was a teacher and of course she had a lot to worry about. But her thoughts drifted not to all the work to be done without, but the work to be done within. She wrote to a friend:

Often in our prayers, at the fag-end of the day and tired out, we mumble a set of words… So to remedy, so far as in me lies, two great evils, I have made up my mind as soon as tea is over, when I feel quite fresh, I will devote half or three-quarters of an hour to Bible reading and earnest prayer.[1]

The young woman was Charlotte Mason and she made good on her resolution: she developed a lifelong habit of prayerful meditation on the Holy Scriptures. She left a written account of her reflections “which we can trace in verses written from about the age of twenty-five,” including “an old notebook” with entries that can be dated to 1871.[2] But day after day as she was contemplating the text of her Bible, she was also contemplating the nature of education. The reason for this second field of contemplation was that she was frustrated:

I had at the time just begun to keep school, and was young and enthusiastic in my work. It was to my mind a great thing to be a teacher; it was impossible but that the schoolmistress should leave her stamp on the children. Hers was the fault if anything went wrong, if any child did badly in school or out of it. There was no degree of responsibility which youthful ardour was not equal to. But, all this zeal notwithstanding, the disappointing thing was, that nothing extraordinary happened.[3]

Mason read widely to see if there was some gem in the history of education that would help her become more effective as a teacher. However, her searches turned up empty:

Looking for guidance to the literature of education, the doctrines of Pestalozzi and, still more, of Fröbel were exceedingly helpful to me as showing the means to secure an orderly expansion of the child’s faculties, and what is even more important, pointing out as they both do, that the child is, so to speak, an exotic which can flourish and expand only in a warm temperature of love and gentleness, regulated by even-handed law. At the same time, religious teaching helped the children, gave them power and motives for continuous effort, and raised their desires towards the best things. But with these great aids from without and from above, there was still the depressing sense of working education in the dark: the advance made by the young people in moral, and even in intellectual power, was like that of a door on its hinges—a swing forward to-day and back again to-morrow, with little sensible progress from year to year beyond that of being able to do harder sums and read harder books.[4]

Nevertheless she began to find answers, perhaps from an unexpected source. Her notebooks reveal that from the text of Scripture she began to see the model for a different approach to education. According to biographer Essex Cholmondeley:

The thoughts expressed show that the main truths underlying her future work were already clearly in mind: for example, the vision of children in their essential simplicity, the wonder of law, of growth, the power of knowledge, love and faith.[5]

Cholmondeley’s assertion that it was “upon that ‘life hid with Christ in God’ … which she based her teaching”[6] was confirmed by Mason’s close friend Agnes Drury, who wrote:

She has herself told us that she has drawn her philosophy from the Gospels, where we may study and note “the development of that consummate philosophy which meets every occasion of our lives, all demands of the intellect, every uneasiness of the soul.”[7]

In the winter of 1885–1886, Mason unified these two threads of her inner life and presented a philosophy of education in a series of lectures entitled “Home Education.” In these lectures she announced that she had discovered “a code of education in the Gospels, expressly laid down by Christ.”[8] In the seventh lecture, she made an astonishing reference to the circumstances of her own resolution as a nineteen-year-old:

In the first place, “every word of God” is the food of the spiritual life; and these words come to us most freely in the moments we set apart in which to recollect ourselves, read, say our prayers. Such moments in the lives of young people are apt to be furtive and hurried; it is well to secure for them the necessary leisure—a quiet twenty minutes, say,—and that, early in the evening; for the fag end of the day is not the best time for its most serious affairs. I have known happy results where it is the habit of the young people to retire for a little while, when their wits are fresh, and before the work or play of the evening has begun.[9]

By 1892, Mason had started the House of Education to help teachers learn about her philosophy and method of education. Since the Gospels were at the heart of her philosophy, it is no surprise that within three years they became the heart of the House of Education as well:

From 1895 until 1922 Miss Mason held a Sunday class with her students, using the findings of her own meditations which she wrote day by day for many years.[10]

An ex-student of the House of Education describes this Sunday class as follows:

At 4-15 on Sunday afternoons we used to go into the drawing room for “meditations” with Miss Mason. We used to read passages of the Bible to her and then she would discuss the passage, giving her thoughts and trying to get ours on the subject. The various volumes of “The Saviour of the World” were really the outcome of “meditations” with former students. It was during that hour that we saw more clearly than at any other time how closely she lived with God… I think of all the “Meds” at which I was present, I appreciated her talks at Whitsuntide most of all. She was so full of the Holy Ghost herself that her very words seemed to have been inspired.[11]

Cholmondeley asks, “What thoughts of God, the outcome of her inner story, did Charlotte Mason bring before the minds of her students Sunday by Sunday?” Then she answers her own question:

The love and knowledge of God, of Jesus Christ the Saviour of the world, of the Holy Spirit as supreme educator of mankind, these themes are never absent from her thoughts. To reach such knowledge each person must feel the need to know. A keen desire, a full attention given to the words of life, the will to receive them, to ponder, to keep them—this attitude of mind gives entry into the world of truth which is the life of the world to come, the Kingdom of Heaven, for the mind fully given is a humble mind, free from self-concern, ready to enter, to receive and to share with others the bread of life.[12]

In other words, the key ideas of the Sunday meditations were none other than the key tenets of Mason’s philosophy of education.

The same year that the Sunday meditations were introduced, the House of Education was moved to a building called “Scale How.”[13] Cholmondeley describes the structure as follows:

This house on the hill, Scale How, is a large grey house of Georgian proportions, backed by hilly country which rises to the heights of Fairfield.[14]

Two years after introducing the Sunday meditations at the House of Education in Scale How, Mason shared with the readers of The Parents’ Review about the importance of meditation:

It has long been known that progress in the Christian life depends much upon meditation; intellectual progress, too, depends, not on mere reading or the laborious getting up of a subject which we call study, but on the active surrender of all the powers of the mind to the occupation of the subject in hand, which is intended by the word meditation.[15]

A few months later, Mason announced that she would no longer limit her weekly meditations to the House of Education. Rather, she would also send them out to subscribers:

It is our habit to read through, from Sunday to Sunday, one of the four Gospels, with comments which are more in the nature of a practical meditation than of a lecture or of a lesson. The students who are at work in their various posts miss this weekly stimulus to the higher life; and, in order to help them, some of the students still in training are taking notes so that these weekly “meditations” may be published.[16]

In 1898, a sufficient number of subscribers was obtained, and Mason began printing and mailing out her meditations. She entitled them “Scale How ‘Meditations,’” perhaps because the Sunday meditations were always associated with the house in which they were first practiced. Sadly, however, the subscription model proved unsustainable and the mailings were discontinued after only a year. Nevertheless, Mason’s faithful assistant Elsie Kitching kept her own copy of each of the mailings. In fact, she even hand-bound them into her own little book.

Although the publication of weekly meditations ceased, the monthly publication of The Parents’ Review flourished. In 1906, Mason wrote an article entitled “Meditation” in which she explained more fully the meaning of this “intellectual habit”[17] that she had alluded to in 1897:

Christianity is not merely the following of Christ, but is chiefly, the knowledge of Christ, to be attained by a constant, devout contemplation of the Divine Life. Hence, the primary importance of meditation to the Christian soul. We cannot grow into the likeness of that which is unknown to us, and we cannot know except by that process of reflective contemplation which we name meditation.[18]

In her article, she asks the obvious question we all might ask: “How, and how early, may children be led to meditate?”[19] She begins to relate how a Bible lesson is properly conducted, including narration and all the elements we would expect from Charlotte Mason. After describing the canonical practice, she surprises us by writing:

But all this is not meditation? No; but at the end, the mother, or teacher, might say, “You awake sometimes before nurse comes. If you should do so to-morrow, you might tell this story to yourself without leaving out a word.” This is one of the pleasant things a child will love to do; and here we have meditation, not in its initial stage, but in perfection; because this act of mental narration has the curious effect of bringing before the mind’s eye the persons and the action of the tale, somewhat as they would appear in a cinematograph; and, with the progress of the story and the action of the figures, come into the mind the ideas proper to it—you meditate in the fullest sense of the word.[20]

Here Mason explicitly equates meditation with “mental narration,” an act that is by definition an act of solitude. I like to call it “narration of the heart.”[21] One may doubt its efficacy, but Mason defended the practice with a challenge in 1914:

All the acts of generalization, analysis, comparison, judgment, and so on, the mind performs for itself in the act of knowing. If we doubt this, we have only to try the effect of putting ourselves to sleep by relating silently and carefully, say, a chapter of Jane Austen or a chapter of the Bible, read once before going to bed. The degree of insight, the visualization, that comes with this sort of mental exercise is surprising.[22]

In 1908 Mason revisited the meditations she had sent to subscribers in 1898. Beginning in the March issue of The Parents’ Review, she began republishing the earlier Scale How Meditations on a monthly basis. However, she changed the title: no longer “Scale How ‘Meditations,’” she called them “Sunday ‘Meditations’” in The Parents’ Review. The final meditation was included in the June 1909 issue. Despite the title change, the reprints were nearly the same as the 1898 originals. However, Mason did make a few edits. One fascinating alteration seems to have been motivated by a desire to avoid a possible theological controversy.

Once the full set from 1898 had been republished in The Parents’ Review, they would forever be included in the large, bound hardcover volumes of this famous PNEU journal. The original leaflets would be presumed lost, if not for faithful Elsie Kitching, and that little handbound copy she kept: the original “Scale How ‘Meditations.’”

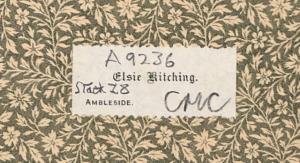

Providentially, Kitching’s little book did not get lost amidst all the moves and changes in the PNEU. It still resides on a shelf in the Armitt Library. There is no marking on the cover to indicate the treasure that lies within. However, a personal stamp on the inside cover leaves no doubt as to who assembled the collection. In charming Gothic print we see her name: “Elsie Kitching.”

Providentially, Kitching’s little book did not get lost amidst all the moves and changes in the PNEU. It still resides on a shelf in the Armitt Library. There is no marking on the cover to indicate the treasure that lies within. However, a personal stamp on the inside cover leaves no doubt as to who assembled the collection. In charming Gothic print we see her name: “Elsie Kitching.”

Why read the Scale How Meditations today? Mason answered the question once and for all in the very first meditation:

When we feel dead and indifferent we are not intended to work ourselves up to a condition of greater fervour; what we want is a new idea of the spiritual life which will act upon that life as does a meal upon a sinking frame. We are to be transformed by the renewing of our minds, and with the renewed vigour given by new thoughts of God we are enabled once more for the spiritual activities of prayer, praise, and godly endeavour. In our Sunday talks at the House of Education, we seek for the nutriment of new ideas, and we look for them in one or another of the Gospels, as these afford the most abundant supply of that of which we are in search.[23]

Mason said that “life is sustained on ideas.”[24] The Scale How Meditations are full of ideas to sustain and invigorate your spiritual life and that of your family. But I would like to suggest another reason to read the Meditations.

Agnes Drury said that Mason “told us that she has drawn her philosophy from the Gospels.”[25] But the links in the chain of Mason’s reasoning from the Scriptures to the volumes is not always self-evident. Why did Mason say that children are born persons? Why did she believe knowledge is so important? What makes nature study so special? We can guess at the answers when we guess at Mason’s sources. But in the Scale How Meditations, the guesswork is taken away. She reveals the core Scriptural principles from which the rest are drawn.

Because of the importance of these documents, Dr. Benjamin Bernier published an annotated version entitled Scale How Meditations in 2011. This softcover edition is available from lulu.com, and a PDF version may also be purchased. Bernier’s edition also includes Mason’s 1906 Parents’ Review article entitled “Meditation,” as well as three additional meditations not included in the 1898 series. Bernier’s preface, introduction, and abundant footnotes explain the history and theological setting of many of Mason’s reflections. He also indicates when each 1898 meditation appeared in The Parents’ Review.

We are also excited to share that Nancy Kelly is announcing a new hardcover edition of Scale How Meditations. After many years of drawing from the meditations in her Living Education Lessons, she desired to produce a beautiful hardcover for personal study and devotion. Thanks to Riverbend Press, this dream is now a reality. This new edition includes the Parents’ Review versions of the 1898 meditations, five other articles and meditations by Mason, and a fold-out print of a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

To complement these welcome resources, the team at Charlotte Mason Poetry has decided to transcribe the original meditations from Elsie Kitching’s notebook and share them online for free. As with all of our transcriptions, they follow the highest standards of accuracy and quality. Our edition will also include the Bible text for each meditation from the English Revised Version, the translation used by Mason in her 1898 Sunday sessions. Our plan is to release one meditation each week beginning this Saturday. We hope you will read along with us, and let the Gospel of John, along with Charlotte Mason’s reflections, give you “new thoughts of God” and enable you “once more for the spiritual activities of prayer, praise, and godly endeavour.”[26]

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

Endnotes

[1] The Story of Charlotte Mason, p. 185.

[2] Ibid., p. 179.

[3] Home Education, first edition (1886), p. 68.

[4] Ibid., pp. 69–70.

[5] The Story of Charlotte Mason, p. 183.

[6] Ibid., p. 179.

[7] L’Umile Pianta, May, 1914, p. 64.

[8] Home Education, first edition (1886), p. 9.

[9] Ibid., p. 228.

[10] The Story of Charlotte Mason, p. 186.

[11] In Memoriam, pp. 92–93.

[12] The Story of Charlotte Mason, p. 188.

[13] Charlotte Mason: Hidden Heritage and Educational Influence, p. xix.

[14] The Story of Charlotte Mason, p. 56.

[15] The Parents’ Review, volume 8, p. 483.

[16] Ibid., p. 742.

[17] The Parents’ Review, volume 8, p. 482.

[18] The Parents’ Review, volume 17 , p. 707.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., p. 708.

[21] “The Role of Knowledge in Moral Development,” slide 14.

[22] The Parents’ Review, volume 25, p. 16.

[23] The Parents’ Review, volume 19, p. 222.

[24] Parents and Children, p. 39.

[25] L’Umile Pianta, May, 1914, p. 64.

[26] The Parents’ Review, volume 19, p. 222.

2 Replies to “The Story of Scale How Meditations”

My budget is very tight right now so it gives me great joy to know that you all will be generously giving of your time and effort to publish the meditations for free. Thank you for this gift!

This is why I love using this method of education in our homeschool, since the Soul, mind and Spirit learn each day mediating on His word and teachings . How blessed we are by Miss Mason’s wisdom!