Where Your Quotes Are, There Will Your Heart Be Also

The stated goal of classical education theorists is to recover the tradition of classical education and apply it to the contemporary context. Some people suggest that Charlotte Mason was herself a classical education theorist. They say that Mason intentionally linked her ideas with the ideas of the classical past and brought them forward to her contemporary context. They offer as a line of evidence that Mason frequently quotes various educational philosophers from the classical tradition. Their rationale is, ‘where your quotes are, there will your heart be also.’ If Mason references classical thinkers, then she must be classical… or so they say.

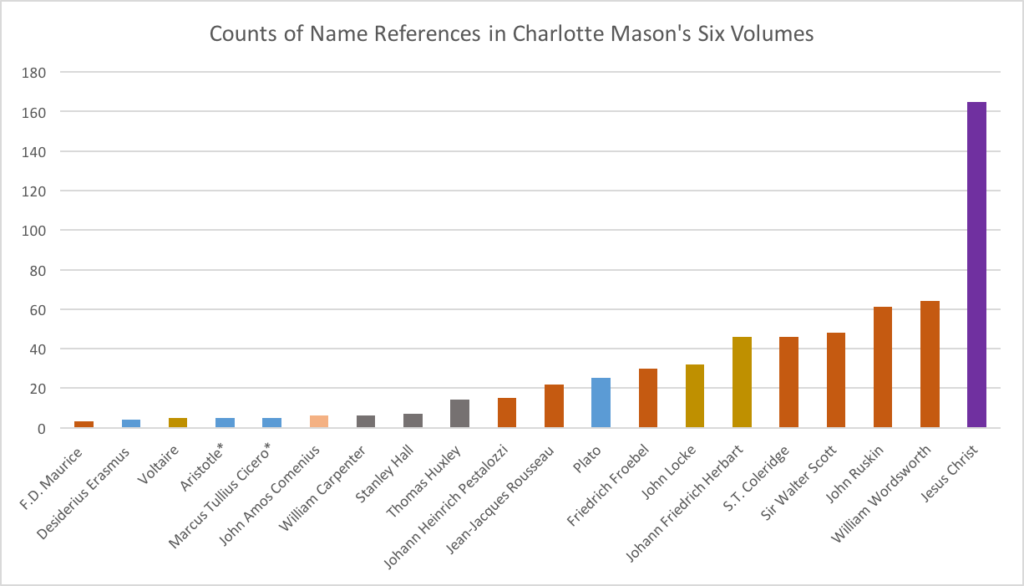

Let us suppose for sake of argument that density of references does in fact reveal philosophical commitment. Wouldn’t it be interesting to see the distribution of Mason’s references? Wouldn’t that show where her heart lies? Let’s take a look! Below is a chart that shows the number of explicit named references to various thinkers and writers in the 2,000+ pages of Mason’s six educational volumes:

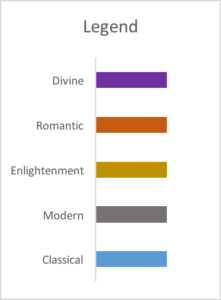

In this chart, I have color-coded the tradition to which each thinker or writer belongs:

I have left John Amos Comenius (1592-1670) unclassified because although he rejected the classical tradition, he is not normally considered a romantic or enlightenment thinker. However, he is definitely linked to those later philosophies, as indicated by Barbara Beatty:

Comenius believed all children should be educated together because God had made all persons in His image. As traditional, classical methods of education had obviously failed to make men and women pious and capable of living together in harmony, he also thought new educational methods were necessary. Like later Enlightenment and romantic philosophers, Comenius looked to nature to provide the guidelines for a new pedagogy. (Preschool Education in America: The Culture of Young Children)

For more information about the place of Comenius in the history of education, please see my article entitled “The Father of Modern Learning.”

In the chart, we see “modern” thinkers such as Carpenter, Hall, and Huxley, who provide insights into science and physiology. We also see “enlightenment” thinkers who emphasize reason and individualism rather than tradition. We see “romantic” thinkers and writers who also emphasize individualism, but lean more towards emotion and a reverence for nature. Finally, we see “classical” thinkers, philosophers of Ancient Greece and Rome and of later ages who receive and adopt that tradition.

From the latter category, we find four references in Mason’s writings to Erasmus (1466-1536). We also find five references to Aristotle and Cicero respectively. Although it should be noted that both Aristotle and Cicero are featured in Mason’s favorite fresco, located in the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella. Mason mentions each of these thinkers three times when noting their inclusion in the fresco. Outside of that, there are only two references. Think about it — two references to Aristotle across 2,000 pages.

Moving to the right on our chart, we come to Plato. His name appears more than the other classical thinkers. I examined every reference in Mason’s writings not only to Plato but also to Platonic. Here is what I found:

1. Six of Mason’s references to Plato are in the context of lessons. Mason is speaking of Plato as a subject of either direct or indirect study. Plato is simply a figure of history, mentioned by Mason in the same way as we might mention George Washington or Leif Erickson. These references indicate nothing about Mason’s relationship to the classical tradition.

2. One reference is in an index and one reference is in a question in an appendix. These references also indicate nothing about Mason’s philosophical commitment.

3. Two references appear in book reviews at the end of volume 5. These references appear in Mason’s brief summaries of the contents of each book. Since they reflect the viewpoint of the reviewed authors, they do not indicated anything about Mason’s relationship to the classical tradition.

4. Two references are to Plato as an example of a historical figure of distinction. For example, she mentions him along with Darwin as an example of genius. These are simply statements of historical fact, and say nothing about Mason’s philosophical commitments.

5. One reference compares Plato to Froebel. Since this is a statement about Froebel’s ideas and not Mason’s, it does not indicate Mason’s relationship to the classical tradition.

6. Two references appear in discussions on the question of censoring books for young people. These discussions have more to do with historical precedent than philosophical commitment.

7. Eleven references appear in Mason’s multiple expositions of her theory of ideas. As I show in my article on Coleridge and the Great Recognition, Mason’s theory of ideas is not derived from Plato. Thus her theory of ideas should not be taken as an indication that she was seeking to revive Platonic philosophy in her contemporary context.

8. In one reference, Mason approves of Plato’s view that mathematical reasoning does not apply to other aspects of life: “Plato formed a just judgment on this matter, too, and perceived that mathematics afford no clue to the labyrinth of affairs whether public or private” (VI:147). There is no indication that Mason derived this idea from Plato or was urging its acceptance solely on the basis of Plato’s testimony.

9. One reference occurs in Mason’s assertion that certain truths can only be accepted by faith. One is belief int he Holy Scriptures:

“Thou canst not prove the Nameless,

Nor canst thou prove the world thou movest in,

For nothing worthy proving can be proven,

Nor yet disproven.”

Plato has said the last word on this matter for our day as well as his own. (VI:195)

Again, there is no indication that Mason derived this widely-accepted idea from Plato or was urging acceptance solely on the basis of his testimony.

10. Three references relate to Mason’s view that knowledge is the key to moral development. Twice she cites “the Platonic saying, ‘Knowledge is virtue,’” and once she writes, “Plato hints at some such thought in his contention that knowledge and virtue are fundamentally identical…” The first of these three reference occurs in volume 2 (p. 271) when she first describes the famous fresco in the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella. But she had already fully defined her Great Recognition before ever seeing the fresco, as I explain in my article about the Great Recognition that Mason brought to Florence. Later, in 1914, Mason would speculate that the Florentines derived their conception not from the Ancient Greeks, but from “the scattered hints which the [Hebrew] Scriptures offer.”

The the other two references occur in volume 6 (pages 127 and 235). It is interesting that John Dewey quotes the very same axiom of Plato: “Plato’s conviction that knowledge and action are one does not fail him at any point in the scale of insight.” Of course, no one would accuse John Dewey of attempting to revive classical education for a contemporary context. Dewey’s example shows that a thinker can quote Plato and yet make educational recommendations that depart from the classical tradition.

In fact, Mason does just this. In volume 6, she mentions Plato’s axiom at the start of Book II, Chapter 1. But after a few pages of development, she reaches a conclusion that is as dissimilar to classical education as the conclusions of Dewey:

If we realise that the mind and knowledge are like two members of a ball and socket joint, two limbs of a pair of scissors, fitted to each other, necessary to each other and acting only in concert, we shall understand that our function as teachers is to supply children with the rations of knowledge which they require; and that the rest, character and conduct, efficiency and ability, and, that finest quality of the citizen, magnanimity, take care of themselves. (VI:240)

Mason’s radical conclusion is that the teacher’s function is only to supply children with knowledge. The rest, character, conduct, and (shall we say) virtue, “take care of themselves.” What a stark contrast to David Hicks’s defining vision of classical education:

Students become the disciples of their teacher, so to speak… Teachers then exercised such a profound influence over their students that the charge against Socrates of corrupting youth was not at all an uncommon one… Socrates himself identified this strong spiritual bond between the master and his pupils as eros, the source of virtue in learning. (Norms & Nobility, p. 41)

As with all contemporary Classical Education theorists, Hicks looks to the ancients for patterns and principles of education which can be revived in the present. Thus, Hicks identifies the “spiritual bond between the master and his pupils” as “the source of virtue in learning.” But since Mason is not a classical education theorist, she (like Dewey) references a broad axiom of Plato, and then proposes a principle and practice of education that radically departs from the classical tradition.

Mason does indeed refer to Plato’s saying as an “axiom.” Does the use of that word alone make Mason a classical education theorist? It should be observed that Mason cites other axioms For example, “HUXLEY’S axiom that science teaching in the schools should be of the nature of ‘common information’ is of use in defining our limitations in regard to the teaching of science” (VI:218). Mason is no more tied to Plato than she is to Thomas Huxley.

11. The final reference is negative. For Mason, the scientific era meant the end of the Platonic metaphysic. Mason writes:

M. Fouillée Neglects the Physiological Basis of Education—In a word, M. Fouillée returns boldly to the Platonic philosophy; the idea is to him all in all, in philosophy and education. But he returns empty-handed. The wave of naturalism, now perhaps on the ebb, has left neither flotsam nor jetsam for him save for stranded fragments of the Darwinian theory. Now, it is to this wave of thought, materialistic, what you will, that we owe the discovery of the physiological basis of education. (II:123)

The physiological basis of education was one of the key pillars of Mason’s method. She saw the human person as a physical-spiritual fusion. She organized her theory of education around this fusion, including her theory of ideas. She did not adapt or adjust Plato’s idea; rather she synthesized information from the Holy Gospels, her own observations, and the discoveries of science.

Interestingly, Mason makes a second negative reference to Plato in her Scale How Meditations. She writes:

“I am of Philo,” “I am of Plato,” “I am of Moses,” “I am of Christ,” men would say, each believing that he held the whole truth; and earnest souls would vex themselves about the differences between Christian and Platonic teaching then, as they do to-day about the disparities between the revelation of Scripture and that other revelation of Science, which no man is yet able to reconcile. (Parents’ Review 19:224)

In this fascinating paragraph, Mason says that no man has been able to reconcile Scripture with science. She says that the same problem existed in the past. In other words, in Mason’s view, no man has been able to reconcile Christian and Platonic teaching.

The limits of what one can deduce from Mason’s complete set of references to Plato are as follows:

- Platonic philosophy cannot be reconciled with Christian teaching (Parents’ Review 19:224).

- Platonic philosophy cannot be reconciled with the physiological basis of education (II:123).

- Plato’s axiom that “knowledge is virtue” provides indirect support for Mason’s conclusions which are as far from classical education as are the ideas of John Dewey.

- Plato’s philosophy of ideas is loosely related to Mason’s distinct and dissimilar theory of ideas as symbolic representations of truth and life emanating from Christ.

- Plato wrestled with questions of censorship, mathematics, and faith, as have every generation of educators from ancient times to the present day.

- Plato was a genius and an important historical figure.

These deductions make it obvious that Mason is not attempting to bring classical principles of education forward to the contemporary context.

Returning to our bar chart, we see that Plato’s lonely blue bar sits in a sea of orange. For example, Mason references Rousseau nearly as often as Plato. However, while she calls Plato a “great mind” (III:224), she refers to Rousseau as a “great teacher” (II:2). In fact, she goes as far as to refer to Rousseau as a “preacher of righteousness” (II:3), a title that would be unacceptable to a Classical Education theorist. For example, Hicks writes of Rousseau, “Isokrates had little in common with the modern teacher who fantasizes an ideal child and bases his child-centered learning on the nostalgic writings of Rousseau” (Norms and Nobility, p. 38). Mason’s preacher of righteousness is dismissed by classical educators as “nostalgic.”

Moving farther to the right of the chart, the overwhelming preponderance of Mason’s references are to thinkers in the romantic tradition. The penultimate bar is William Wordsworth. Does Mason reference Wordsworth merely as a subject of study? Is he merely a good source of material for poetry study? Or does he actually inform Mason’s theory of education?

Mason’s first principle is that “Children are born persons.” Classical Education theorists interpret this principle incorrectly, asserting that Mason is intending to counter contemporary scientific thought. They do not accept that Mason is actually intending to counter classical thought. The implications have many dimensions, but one dimension is informed by Wordsworth himself, quoted by Mason in volume 5:

Your love hath been, nor long ago,

A fountain at my fond heart’s door,

Whose only business was to flow;

And flow it did; not taking heed

Of its own bounty, or my need.

Mason applies this quotation as follows:

There is in the heart of every child a fountain of love,

“Whose only business is to flow”;

and this it is the part of the parents to keep unsealed, unchoked, and flowing forth perennially in the appointed channels of kindness, friendliness, courtesy, gratitude, obedience, service. (V:204)

Mason directly contradicts the classical tradition’s perception of “childhood as a period of becoming rather than as a state of being” (Hicks, p. 38). Mason directly contradicts the classical tradition’s notion that virtue must be aggressively imposed by the teacher from without. Instead, Mason asserts that “There is in the heart of every child a fountain of love…” Parents (and teachers) do not implant the fountain. They do not fill the fountain. They don’t impose order on the fountain. Rather, they merely keep it “unsealed, unchecked, and flowing forth perennially.”

Where does Mason get such a radical thought? Does she ultimately source this idea in the romantic thinkers that she quotes so frequently — Pestalozzi, Rousseau, Coleridge, Scott, Ruskin, Wordsworth? No! She sources this radical thought in the Teacher she loves the most.

How do we know this? Because ‘where your quotes are, there will your heart be also.’ On the rightmost edge of our chart, one bar towers above the rest, relegating them all to a distant and secondary place. That bar counts Mason’s references to Christ, whose living ideas formed Mason’s theory of education:

“Of such is the kingdom of heaven.” “Except ye become as little children ye shall in no case enter the kingdom of heaven.” “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” “And He called a little child, and set him in the midst.” Here is the Divine estimate of the child’s estate. It is worth while for parents to ponder every utterance in the Gospels about these children, divesting themselves of the notion that these sayings belong, in the first place, to the grown up people who have become as little children. What these profound sayings are, and how much they may mean, it is beyond us to discuss here; only they appear to cover far more than Wordsworth claims for the children in his sublimest reach

“Trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home.”

Code of Education in the Gospels.—It may surprise parents who have not given much attention to the subject to discover also a code of education in the Gospels, expressly laid down by Christ. (I:12)

Mason did not find a code of education in the classical tradition. She found a physiological basis for education that left Platonists “empty-handed.” She found a code of education in the treasure of her heart, the words of the Lord Jesus Christ. To properly interpret Mason’s theory of education, we must look there too.

2 Replies to “Where Your Quotes Are, There Will Your Heart Be Also”

Thanks, Art, for putting this graph together. It is such a great visual to go along with all the other research you are writing about to support the premise that Mason’s philosophy is based on Scripture and that is what sets her apart.

Thank you for reading my article and posting your feedback. And thank you for showing us ways that Mason’s theory of education continues to resonate with the new discoveries of science and the old revelations of the Bible! https://charlottemasoninstitute.com/Blog/4327875