Reflections on The Saviour of the World Volume 5

Book II Poem XXI

Charlotte Mason envisions a scene contrary to all the laws of love and war. A royal prince from a neighboring land comes to pay a visit. An emissary, an ambassador, representing his royal father from abroad. How should he be treated? Don’t we all know?

And yet contrary to all civility and international law, the royal prince is accosted and apprehended by a troop of guards who are normally sent for common criminals.

Where did Mason discover this scene? From a fairly tale or a fable? No, she found it in the Word of God. The royal father is God and the prince is His Son. A troop of guards were sent to apprehend him. How would He respond? Find out in today’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

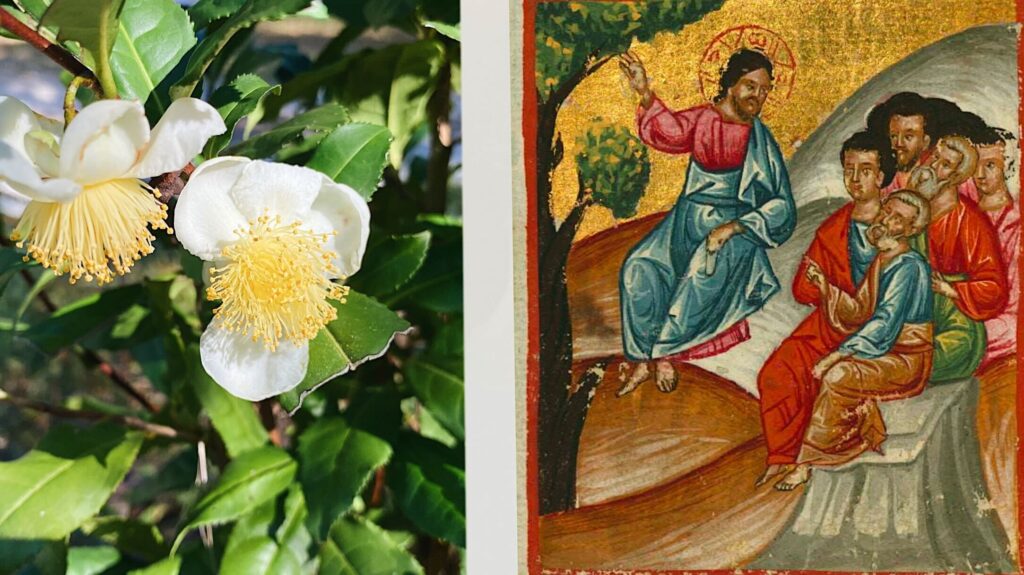

Book II Poem XXII

In Henry Latham’s classic Pastor Pastorum, the author lists a set of principles that he believes were followed by Christ when He was deciding when and which miracles to perform. The fifth principle, he wrote, is that “No miracle [was] worked which should be overwhelming in point of awfulness so as to terrify men into acceptance, or which should be unanswerably certain, leaving no loophole for unbelief.”

Latham mentions the idea of “loopholes” two other times in his book. in both cases, they refer to reasonable and plausible stances to which those “who wanted to escape being convinced” by Christ could retreat and find peace of mind.

This idea is complementary to Charlotte Mason’s “the way of reason,” summarized in point 18 of her synopsis. Reason is fallible, she warned. It is very good at giving us confidence in “an initial idea, accepted by the will.” In other words, it allows us to accept “loopholes” with complacency.

Today’s poem by Charlotte Mason is best understood in light of “the way of reason” and the loopholes to faith. Many heard the words of Christ, but few willed to understand. The rest asked, “What is this word that He saith?” Read or hear it at this link.

@artmiddlekauff

Book II Poem XXIII

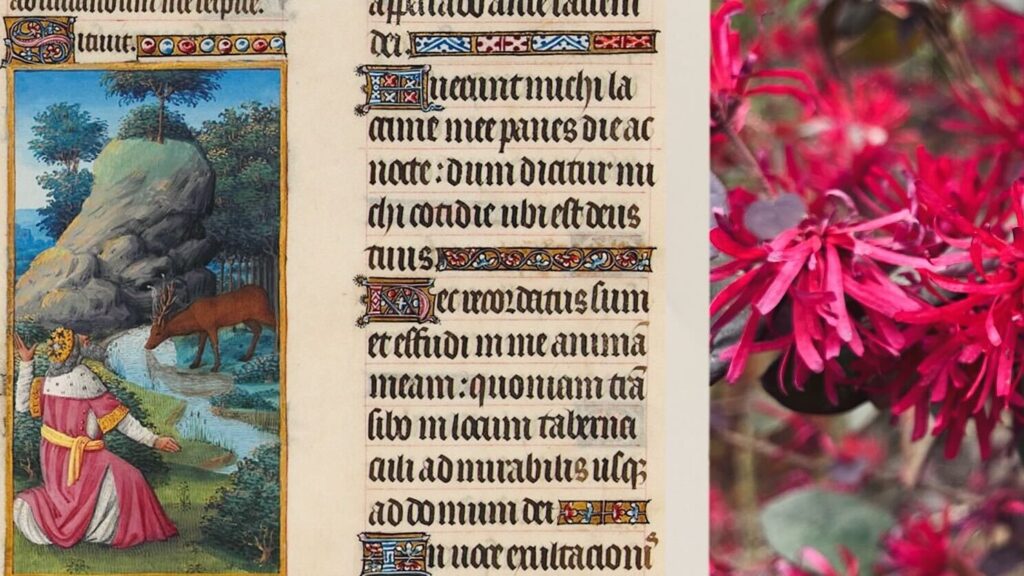

“Once again,” writes C. S. Lewis, “the best image is in a Psalm, the 19th. I take this to be the greatest poem in the Psalter and one of the greatest lyrics in the world.”

Building on Lewis’s lofty assessment, J. Clinton Mccann Jr. writes: “As remarkable as the lyrical quality of Psalm 19, however, is its extraordinary theological claim. In essence, Psalm 19 affirms that love is the basic reality. According to the psalmist, the God whose sovereignty is proclaimed by cosmic voices is the God who has addressed a personal word to humankind—God’s torah.”

In what some consider to be the greatest poem of all time, King David praises the perfect law of God. But how do we imperfect beings face the perfect law? “Cleanse me from secret faults,” David pleads. “Keep back Your servant also from presumptuous sins!”

In her poem on a poem, Charlotte Mason echoes David’s prayer. “How dare I go,” she cries, “exalting my poor wisdom over His”? The title of the poem is her plea, our plea — “Keep back thy servant from presumptuous sin.” Read or hear Mason’s poem here. And may it incline your heart to appreciate David’s’ poem anew.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXIV

In one of Charlotte Mason’s most remarkable texts, now found in Parents and Children, she asks:

Does this doctrine of ideas as the spiritual food needful to sustain the immaterial life throw any light on the doctrines of the Christian religion?

And then she answers:

Yes; the Bread of Life, the Water of Life, the Word by which man lives, the ‘meat to eat which ye know not of,’ and much more, cease to be figurative expressions…

Isaiah cried out, “Ho! Everyone who thirsts, Come to the waters.” For Charlotte Mason, this is an offer for living water, and our thirst is real. In Mason’s dramatic poem on Isaiah 55:1, the dance between the literal and the figurative paints a wondrous truth. Read or listen to Mason’s poem to understand just how thirsty we are. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXV

The book of Ezekiel is filled with images, some disturbing, some confusing, and some mysterious. It is filled with symbols, some clear, some opaque, and some convicting. It is filled with intricate descriptions of buildings, a temple, and an altar, and a measurement of land. But then towards the end of the book the reader encounters an image which, to me, can only be described as beautiful.

After reading about the rules for entering the vast new temple yet to be seen on earth, and how the gate facing east is to be opened for the prince, we read how Ezekiel saw something truly marvelous: water began to flow from the temple to the east. It became a river! And “Along the bank of the river, on this side and that, will grow all kinds of trees used for food; their leaves will not wither, and their fruit will not fail.”

Charlotte Mason’s students read the book of Ezekiel in Forms V and VI. They were told to read the accompanying comments by John R. Dummelow. His statement about the river from the temple is striking: “To Ezekiel this river was not a mere symbol of spiritual refreshment. The perfect kingdom of God still presented itself to him in an earthly form, accompanied by outward fertility and other material blessings.”

In her own way, Mason too felt that this was no symbol. She felt that the living water was real. “Ideas emanating from our Lord and Saviour, which are of His essence, are the spiritual meat and drink of His believing people,” she wrote.

Back in 2016 I was asked to select three poems by Miss Mason to include in a conference notebook. This poem was the third. Yes, the river from the temple is real, in more ways than one. Read or hear Mason’s poem at this link.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVI

Isaiah “should be called an evangelist rather than a prophet,” wrote St. Jerome, “because he describes all the mysteries of Christ and the church so clearly that one would think he is composing a history of what has already happened rather than prophesying what is to come.”

When Charlotte Mason read Isaiah 55, she saw not a prediction of the future but an account of the past. She saw the day that Christ stood up and cried out, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink.”

J. Paterson-Smyth reflects on how Christ continues to call out even to this day:

His voice still comes as we tramp on,

With a sorrowful fall in its pleading tones:

“Thou wilt tire in the dreary ways of sin,

I left My home to bring thee in.

In its golden street are no weary feet,

Its rest is pleasant, its songs are sweet.”

And we shout back angrily, hurrying on

To a terrible home where rest is none:

“We want not your city’s golden street,

Nor to hear its constant song.”

And still Christ keeps on loving us, loving all along.

Rejected still, He pursues each one.

Charlotte Mason’s poem captures the voice of the One who rejected still, still pursues each one. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVII

To be human is to be thirsty. Our bodies cannot live without water, but our souls are thirsty too. But what exactly will quench our thirst?

Catherine Benincasa grew up before the days of running water. As a little girl she would run down a path near her home to a fountain called Fonte Branda. The waters flowed from a hillside spring and were collected in a pool, the walls of which were lower at certain points to let out the overflow. From one of these points she would fill her jug and drink from it. And then the jug would be empty again.

Charlotte Mason noticed the many kinds of jugs that we drink from. There is money, there is pleasure, there is power, and there is lust. And there is love. But even there we do not realize that a man cannot “live by draining another’s cup to allay his thirst.”

Catherine Benincasa grew up and came to know Jesus. She tried to explain about Him, and she remembered the fountain called Fonte Branda. “The blessed Christ is the one who invites us to the living water of grace,” she wrote. “He said as much when he cried out in the temple, ‘Let whoever is thirsty come to me and drink, because I am the fountain of living water.’ He truly is a fountain. For just as a fountain holds the water and lets it spill out over the wall that surrounds it, so does this gentle loving Word, clothed in our humanity, do.

“His humanity was a wall that held within itself the fire of the eternal Godhead which was joined with that same humanity. And the fire of divine charity spilled out through the opened-up wall, Christ crucified. His precious wounds poured out blood mixed with fire, because it was by the fire of love that his blood was shed. From this fountain we draw the water of grace, since it was not merely through his humanity but by the power of the Godhead that human sin was washed away and we were restored to grace.”

Then Catherine added a qualifier. “He says, however, ‘Let whoever is thirsty come to me and drink.’ He doesn’t invite those who have no thirst.” Charlotte Mason’s poetic reflection on these words of Christ penetrates the heart and awakens our thirst. And so we come to the fountain, where the fire of divine charity spills out through the opened-up wall. Read or hear the poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXVIII

In Acts 2 we read of the coming of the Holy Spirit. The believers were all in one place and then “suddenly there came a sound from heaven, as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled the whole house where they were sitting.” Since that day, countless believers have desired and longed for a similar experience with the Holy Spirit of God.

Taking his cue from John 7:39, Joseph Dongell makes several keen observations about the pouring out of the Holy Spirit:

First, it is Jesus who gives the Spirit as water to the thirsty. The Spirit does not stand as a power independent of Jesus, nor as a focus of faith distinct from Jesus. In coming to and believing in Jesus, the Spirit is given.

Second, the gift of the Spirit comes in such abundance that what begins as a quest for a ‘drink’ becomes the discovery of a ‘river’! In many ways, grace far exceeds human expectation and desires, not only at the point of initial faith but throughout the entire course of Christian experience.

Third, this gift of abundant water fulfills the longing of God’s people, a longing witnessed by the Old Testament… All of the deepest desires of humankind are richly supplied in the water Jesus gives.

Fourth, the giving of the Spirit would happen only according to the larger plan of God. Not until Jesus had been glorified would the Spirit be given in the measure Jesus promised. Fulfillment of the Father’s desire to indwell believers would need to await the completion of the Son’s earthly mission.

Charlotte Mason also took her theological cues from John 7:39. Nearly rehearsing the same four observations, she does so in unforgettable poetic form. Read or listen to Charlotte Mason’s verses which point to the one true source of the water of life.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXIX

During yesterday morning’s Idyll Challenge discussion, a participant pointed our attention to the second-to-last sentence of this month’s reading:

A new Renaissance is coming upon us, of unspeakably higher import than the last; and we are bringing up our children to lead and guide, and by every means help in the progress—progress by leaps and bounds—which the world is about to make.

“I checked when this was written,” explained the participant. She noted that it was before World War I. Did Charlotte Mason’s optimism ever change, she wondered, as the devastations of the twentieth century began to unfold?

I quietly explained that Mason’s hope for the future was never based on humanity, philosophy, politics, or patriotism. It was never based on virtue, enlightenment, education, or optimism. Rather, it was always grounded in her faith in a King. At the height of the Great War she wrote:

The great Hope rising upon us out of the present distress is that an era of passionate Christianity is coming, when we shall hear the shout of a King in our midst and shall all stand at attention waiting his word of command, when we shall hasten to do his bidding.

In today’s poem, Mason writes of “an aged man”:

ah, well might he,

Athirst through all his days, lie down and die,

Parched and unsatisfied; what hope might be

That he, old man, should drink and satisfy

That craving, long consumed him?

Though others may doubt, Charlotte Mason always believed there was a hope for young and for old. “Come to Me!” shouts the King. Read or hear her poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXX

Charlotte Mason wrote a set of eleven poems under the heading “The Water of Life.” The full set was inspired by only three short verses in the New Testament. But for Charlotte Mason, the idea of thirst and fulfillment was integral to her philosophy of education, as well as to her philosophy of life.

Three weeks ago when I shared the fourth poem here, I noted that to be human is to be thirsty. We also know that to be human is to be created in the image of God. But sometimes it can be hard to relate the imperfections of our humanity to the perfections of God.

Kazoh Kitamori was born in Kumamoto, Japan in 1916. As a teenager, he read a paper about Martin Luther that inspired a lifelong interest in theology. He became a professor, a pastor, and a writer. He is now remembered by some as the one who “developed the first original theology from the East.”

Emil Brunner describes this contribution as follows: “The theology of Kitamori is the first attempt to make suffering an attribute of God in contrast to the orthodox idea of the happiness of God, which is rather an idea of Platonic philosophy than of the New Testament gospel.”

Dr. Katamori was particularly struck by Jeremiah 31:20 in which we read of God’s yearning for Ephraim. The Authorized Version says that God was “troubled for him.” Katamori found here the gospel of the cross. In a phrase that is hard for the mind to grasp, Katamori noted that “God loves the objects of his wrath.”

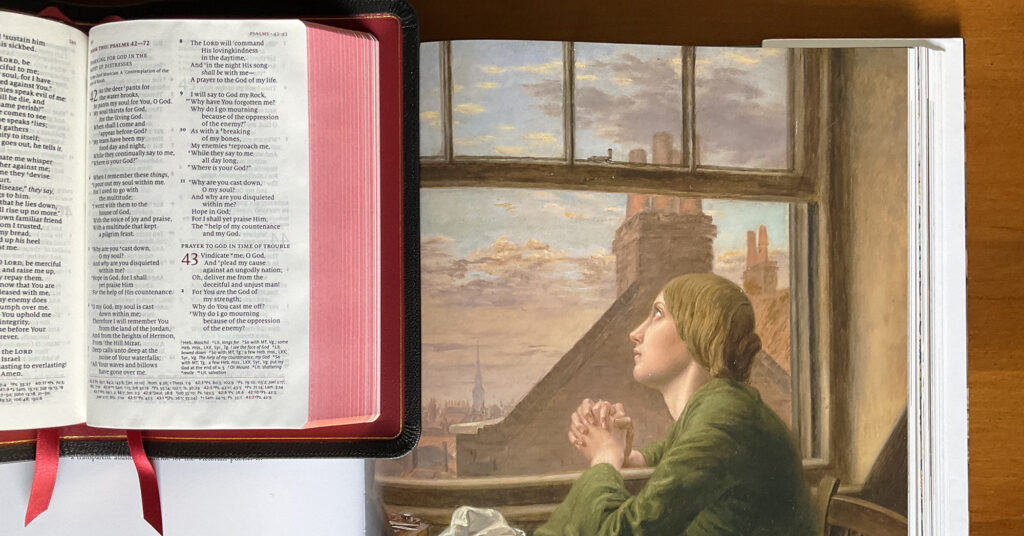

In Psalm 42 the psalmist compared his thirst to that of a panting deer. It is a powerful image of human need. But in one of my very favorite poems of Charlotte Mason, she makes a stunning observation. Two are thirsty. Read and contemplate the moving poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXI

C. S. Lewis writes, “The Christian says, ‘Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger: well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water.’”

“If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy,” he continues, “the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

To be human is to thirst. And there is One who quenches. The scandal, the miracle, is that He thirsted first. Read or listen to Charlotte Mason’s moving poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXII

“In the deep of winter, Herman looked at a barren tree, stripped of leaves and fruit, waiting silently and patiently for the sure hope of summer abundance. Gazing at the tree, Herman grasped for the first time the extravagance of God’s grace and the unfailing sovereignty of divine providence. Like the tree, he himself was seemingly dead, but God had life waiting for him, and the turn of seasons would bring fullness. At that moment, he said, that leafless tree ‘first flashed in upon my soul the fact of God,’ and a love for God that never after ceased to burn.”

That burning love prompted Herman to join the Discalced Carmelite monastery in Paris where he forever became known as Brother Lawrence.

“Men invent means and methods of coming at God’s love,” he wrote; “they learn rules and set up devices to remind them of that love, and it seems like a world of trouble to bring oneself into the consciousness of God’s presence. Yet it might be so simple. Is it not quicker and easier just to do our common business wholly for the love of him?”

Perhaps it was simple for him. But is it simple for us? Perhaps the key lies in the words of his second conversation in The Practice of the Presence of God: “We ought to make a great difference between the acts of the understanding and those of the will; that the first were comparatively of little value, and the others all.”

Those words found their way into a poem by Charlotte Mason. And they find a home deep in the heart of her method. Do you believe in with your understanding, or do you believe with your will? For Brother Lawrence, it made all the difference in the world. And it did for Charlotte Mason too. Read or hear her poem here.

📷 @aolander

@artmiddlekauff

Book III Poem XXXIII

The reader of Parents and Children can be a bit unnerved when reaching Chapter 5. It starts out very promising: Mason proposes to explore “How to fortify the children against the doubts of which the air is full.” But then on the next page she says that “‘Evidences’ are not Proofs.” And in a jarring sentence she claims that “the Christian apologist is open to the imputation conveyed in the keen proverb, qui s’excuse, s’accuse.”

Many parents who love the Charlotte Mason method quietly sidestep this advice. Early on, I followed a well-established Charlotte Mason curriculum whose booklist included works by a well-known apologist. With that for “air cover,” my family enjoyed (and devoured) those books. I never had the sense that by doing so, je m’accuserais.

But I have come to see that Mason was on to something. “The truth by which we live must needs be self-evidenced, admitting of neither proof nor disproof,” she wrote. Her words anticipated the writings of philosopher Alvin Plantinga, who argued that faith in God is “properly basic.” In short, we believe in God because the Holy Spirit tells us to.

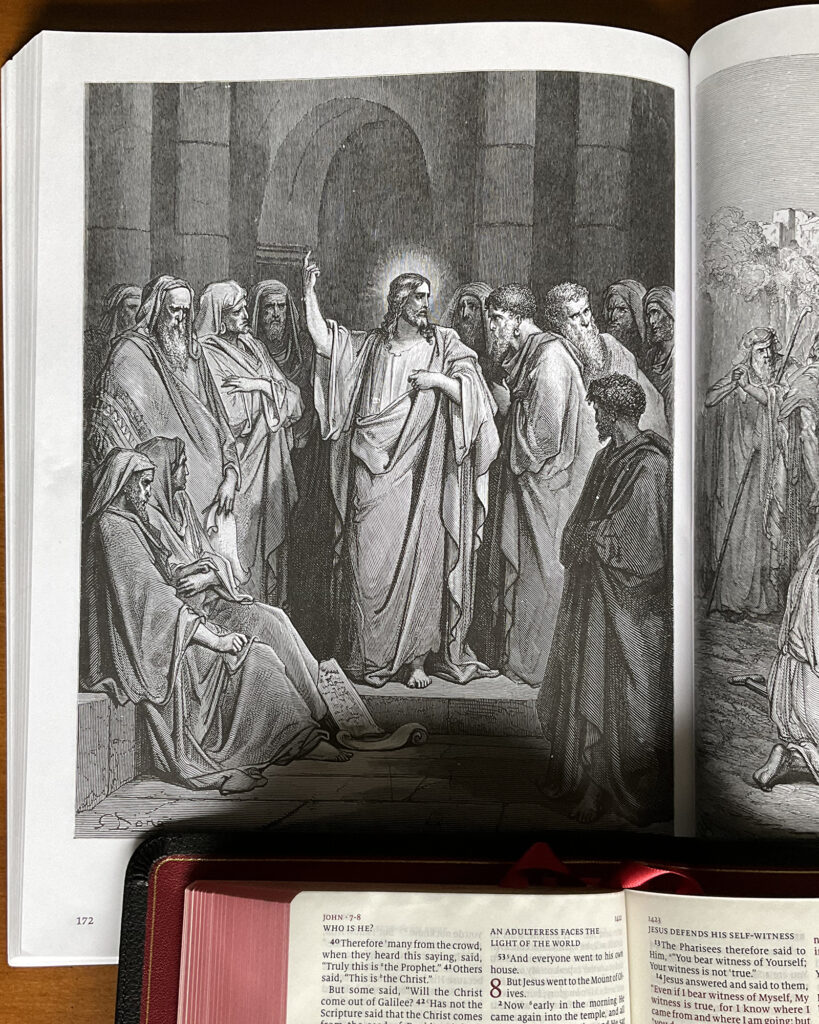

Jesus performed many astonishing miracles. Guards were sent to abduct him, but they were stopped dead in their tracks. Not by signs and wonders or by Christ disappearing from their midst. Not by bolts of lightning or by cracks in the earth. Not by the logic of philosophers or by the authority of leaders. All of their powers and all of their weapons weapons were held at bay by one thing: words. “Never man spake as this Man.”

I love Christian evidences and I love the work of apologists. But there is something that I love even more: the words of Christ. In the company of the Holy Spirit, they stand above proof or disproof. Charlotte Mason’s poem today explores the nature of faith and the reaction of the guards. May you prayerfully read or listen to it, and invite the Holy Spirit to convince you of the truth that admits of no other response but “Yes.”

Find the poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

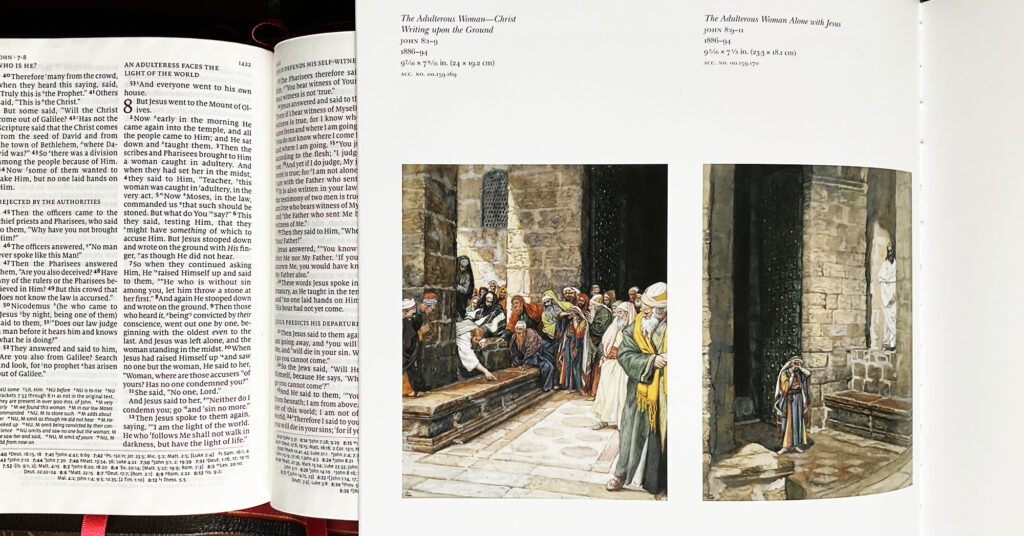

Book III Poem XXXIV

“By laying down for woman the same code of morality, the same standard of purity, as for man; by refusing to countenance the shameless and equally guilty monsters who were gloating over her fall,—graciously stooping in all the majesty of his own spotlessness to wipe away the filth and grime of her guilty past and bid her go in peace and sin no more … [Jesus] has given to men a rule and guide for the estimation of woman as an equal, as a helper, as a friend, and as a sacred charge to be sheltered and cared for with a brother’s love and sympathy.”

— Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892), pp. 17–18

Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s poem about how in the presence of Jesus, no one would cast the first stone. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XXXV

“God is the author of light,” writes St. Ambrose, “and the place and cause of darkness is the world. But the good Author uttered the word light so that he might reveal the world by infusing brightness therein and thus make its aspect beautiful. Suddenly then, the air became bright and darkness shrank in terror from the brilliance of the novel brightness.”

In today’s poem Charlotte Mason celebrates the first day of Creation and all the glory that light brings. But then evening comes, and it is dark again. So Charlotte Mason commences her remarkable series of poems on the Light of the World. Read or hear the beginning here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XXXVI

“Go out now to meet Ahaz,” said the Lord to Isaiah. And so he went and delivered a message of warning: “The Lord will bring the king of Assyria upon you and your people and your father’s house.” But then Isaiah also delivered a message of hope:

“The people who walked in darkness

Have seen a great light;

Those who dwelt in the land of the shadow of death,

Upon them a light has shined.”

Was this also a message for Ahaz and his people? Or was it a message for the whole world?

Cyril of Alexandria said that the law “was likened to a lamp.” It always burned in the tabernacle, but “on account of the shortness” of its rays, its light extended only to those geographically and culturally close enough to the tabernacle to “see” it. “Therefore the Gentiles were ‘in darkness,’ not having this lamplight.”

Isaiah didn’t say that a lamp was coming. He said a *light* was coming. And this light would be for the whole world. Drawing from this prophecy of Isaiah, Charlotte Mason reflects on a world in darkness, hungering not for a lamp but for a light. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

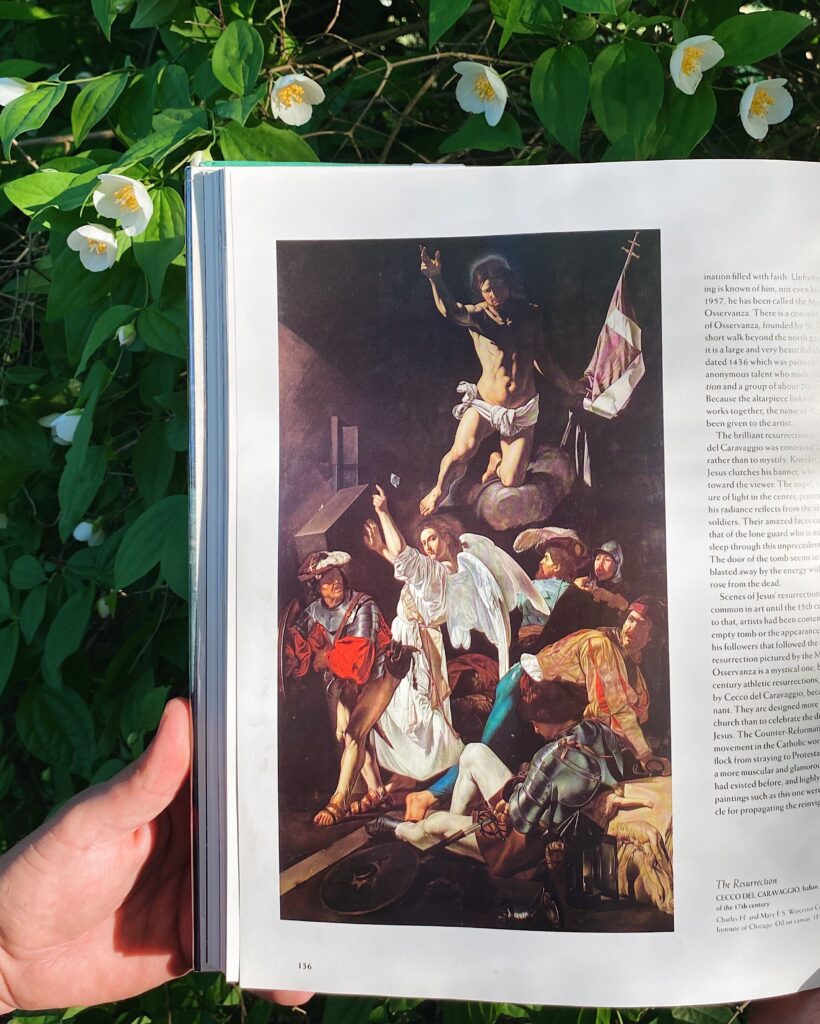

Book IV Poem XXXVII

Readers of Charlotte Mason recognize John Ruskin as the author of “Mornings in Florence,” the book that illuminated the fresco in the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, the fresco that is forever linked with Charlotte Mason’s “Great Recognition.” Ruskin was certainly qualified to write about art; he is widely held to be the leading art critic of the Victorian era.

How many great works of art did Ruskin behold in Florence and beyond? Across a gallery of galleries, Ruskin said that one painting was “for him the greatest work of sacred art ever produced.” Was it perhaps a glorious fresco? A renaissance masterpiece? A holy treasure in Rome?

No. It was Holman Hunt’s 1854 “The Light of the World,” now held in the chapel of Keble College. For Hunt, the work began with the lantern. “The windows and openings had to be carefully studied in relation to the rays they would emit from the central light,” he explained. Hunt wrote up a design and asked an artisan to craft it. The copper model still exists.

Aurélie Petiot explains that “the lantern … illuminates the door at which Christ has just knocked, thus symbolizing salvation.” This light is the subject of Charlotte Mason’s poem which we share today. Mason chose Holman’s painting to accompany this poem in her book. In the light of Holman’s carefully-crafted lantern, we see that the door can only be opened from inside. In her poem, Mason notes that some choose to keep their door closed. And so outside remains a lantern shining more brightly than the sun.

Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

source: The Pre-Raphaelites by Aurélie Petiot

Book IV Poem XXXVIII

Few of Charlotte Mason’s poems have shined more brightly in the hearts of her closest friends than “In the Light.” According to Essex Cholmondeley, the poem is among those contained in a notebook that “can probably be dated 1871.” It was first published on the front page of the December 1902 issue of The Parents’ Review. Then it found a home in The Saviour of the World, published in 1911.

In 1923, In Memoriam was published, containing essays remembering Charlotte Mason. Some were written by members of her inner circle, including Ellen Parish, whom Mason appointed as principal of the House of Education. Parish entitled her essay “Miss Mason’s Message,” and in it she explained “the source of Miss Mason’s teaching.” She included several stanzas of this poem, citing it as one of the foundational expressions of Mason’s thought.

In April 1930, Miss Parish wrote a new paper entitled “Education is the Handmaid of Religion.” It was published in the November issue of The Parents’ Review and closed with the complete text of this cherished poem by her beloved mentor.

The poem contains eight stanzas and captures a dialog between two souls. The first soul is outside the light; the second is “In the Light.” In the final stanza, the first soul expresses her desire to come join the second in the light. But she faces a serious barrier: she feels that she is too vile to enter in. The poem ends with an emotionally powerful and theologically rich response.

Written in 1871, the poem was still being published and read nearly 60 years later. But this poem continues to shine even today. A century and a half after its composition, we invite you to read or hear Miss Mason’s call to join her in the light.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XXXIX

“But in identifying himself as the Light of the World,” observes Joseph Dongell, “Jesus was doing more than playing on the visual imagery of the moment. Light, it must be remembered from the Old Testament, symbolized (among other things) God’s gift of life, the guidance of God, the protection of God, even the very presence of God… Should one understand ‘light’ even in its most limited sense, Jesus’ claim to be the Light of the World constituted a high claim indeed. But to this claim Jesus added a lofty promise: Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life… According to the combined implications of these words, Jesus was offering himself as God’s sole means of salvation for God’s people as well as for the whole world.”

Dongell aptly reasons, then, that “So monumental was this claim that Jesus should have been challenged about His right to make it. Spoken without authority, these words constituted foolish self-promotion (at the least) and blasphemous assault on God (at the most).”

But the Pharisees did not challenge Him on these terms. Rather, they were “crippled by impure motives and rock-solid prejudice against Jesus,” writes Dongell. “The Pharisees began their challenge by noting the principle accepted by Jesus that truth never comes along the line of a single witness, especially a single self-witness: Here you are, appearing as your own witness; your testimony is not valid.”

Charlotte Mason also observed this oddly legal response to Christ’s extraordinary claims. She also observed the escalating conflict which ensued. Read or hear her devout and penetrating poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XL

“But where can wisdom be found?” asked Job, “And where is the place of understanding? … It cannot be purchased for gold, Nor can silver be weighed for its price.”

If wisdom could be purchased, then the knowledge of God would be the reward of the rich. If wisdom could be created, then the knowledge of God would be the reward of the strong. But “think of what you were when you were called,” wrote the Apostle Paul. “Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth.”

It is to these that the Spirit called in Isaiah: “Come, all you who are thirsty, come to the waters; and you who have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk without money and without cost.”

Wisdom — it can’t be purchased for gold, but it can be accepted for free. Commenting on the letter to the Corinthians, Alex R. G. Deasley writes that “once again, Paul grounds the knowledge of salvation in the moral, not the intellectual, realm.”

In today’s poem, Charlotte Mason paraphrases the words of Christ to the strong and powerful:

I know ye can believe, and will ye now,

At the last hour, believe, that I may save?

Just like Paul, Miss Mason locates the knowledge of salvation in the moral, not the intellectual, realm. Read or listen to Mason describe “a door of escape” for whoever “*will* see the truth.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLI

In Bible lessons with my son, we are going through The Saviour of the World. I am savoring every minute, because I know this is my last journey through the volumes with one of my children. We are in volume 4, and with each Bible passage and each poem, we dig deeper into Scripture than ever before.

I am growing to appreciate the distinctive rhythm of the poems; most of the poems deal directly with the Gospel history, and bring the facts of Christ to life. But interspersed at certain intervals are the “disciple” poems. When they come up I remind my son, “This is one of the poems about Christian life today.”

These poems are especially valuable for devotional reading. They help the reader to see how the Gospels speak to us today. But they are also valuable to students of Charlotte Mason’s theology. The other night I had a dream that met Miss Mason in person. But now I realize that I meet her every time that I read one of her poems. Especially her “disciple” poems.

In John 8:26 Jesus says, “I have many things to say and to judge concerning you.” What might that mean to a Christian today? What might that have meant to Miss Mason herself? Read or hear her poem to get a special glimpse inside the heart of an educational theorist whose first love was for Jesus Christ. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLII

In the Gospel of John, we read that Jesus said, “When you lift up the Son of Man, then you will know that I am He.” The Greek word for “lift up” (ὑψόω) also means “exalt.” What is Jesus referring to in this saying?

Charlotte Mason provides an interpretation in her poem about the day that Jesus pleaded “in passionate urgency with the men He had come to save.” Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIII

“Now Eli was very old; and he heard everything his sons did to all Israel,” we read in 1 Samuel 2. Eli’s sons were notorious sinners. And Eli rebuked them with a chilling rebuke that should have pierced even the hardest heart: “If one man sins against another, God will judge him. But if a man sins against the Lord, who will intercede for him?”

But his sons did not listen.

John R. Dummelow in his One Volume Commentary offers sobering comments on this verse. “We say that after a man has persisted for long years in sinful habits, he finds it impossible to alter. The Bible expresses the same truth by stating, first that the sinner (e.g. Pharaoh) hardens his own heart, and then that God hardens the sinner’s heart.”

Eventually the one who sins becomes a slave to sin. He cannot break free. Even God Himself, it seems, will not let him go.

But if One came who could set a person free? Could He make the impossible possible? Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s poem about how to be free indeed. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIV

The Gospel of John records some of the sharpest verbal clashes between Jesus and his auditors. In an explosive incident exposited by Samuel Ngewa, Jesus’s listeners “were indignant at Jesus’ suggestion that they did not have the same father as his. They insisted that Abraham was their Father.”

“So Jesus pointed out that sonship to Abraham and a desire to kill Jesus were in contradiction,” explains Ngewa. “Abraham, a friend of God who is the Father of Jesus, would not do that. Their actions showed that they could not claim Abraham as their father… As the Akamba say, mauta ma kwivaka mainoasya [‘oil applied on the body does not make one fat’].”

In Charlotte Mason’s poem on this sobering passage, she calls on readers to “Rise up, come forth; Behave as Abraham’s seed, and quit the place Where sinners be.” Read or hear Mason’s poem and apply oil not to the body, but to the heart. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLV

Charlotte Mason’s twelfth principle introduces a phrase famously associated with her method: “Education is the Science of Relations.” The principle asserts that the child is born with aptitudes and abilities that equip him for self-education. In the 1923 book In Memoriam, Ellen Parish attempted to explain the source of this and other key elements of the Charlotte Mason method. She pointed to a common source for them all: the Holy Gospels.

For Principle 12, Parish pointed to Mason’s poem “What is truth?” This poem is included in Volume 5 just after Mason explores Christ’s words about truth in John 8:45–47. However, the title of the poem clearly evokes John 18:38, when Pontius Pilate asks “What is truth?” Mason’s poem points directly to that moment, opening with the line, “Nay, what is truth? the cynic lightly cried; But not to him the Incarnate Truth replied.”

From this starting point, Mason proceeds to an inquiry about truth, and she points out that light, music, harmony, and truth all presuppose persons with senses to apprehend such things. The poem closes with these lines: “As though that simple man would say, ‘The light Is its own evidence for men with sight!’”

Mason’s twelfth principle asserts the presence of “first-born affinities [t]hat fit our new existence to existing things.” As teachers, we assume our children are born with sight. Read or listen to the poem that, according to Ellen Parish, lies behind this inspiring thought. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVI

My son and I are reading Book II of Ourselves together, and we are struck by how deep and dense it is compared to Book I. We recently read a few pages packed with intricate and abstract ideas, and I wondered what he would focus on in his narration. Which of the many rich thoughts would resonate with him the most?

To my surprise, he focused on a particular paragraph, which he retold with clarity and insight. In the original text, Charlotte Mason writes:

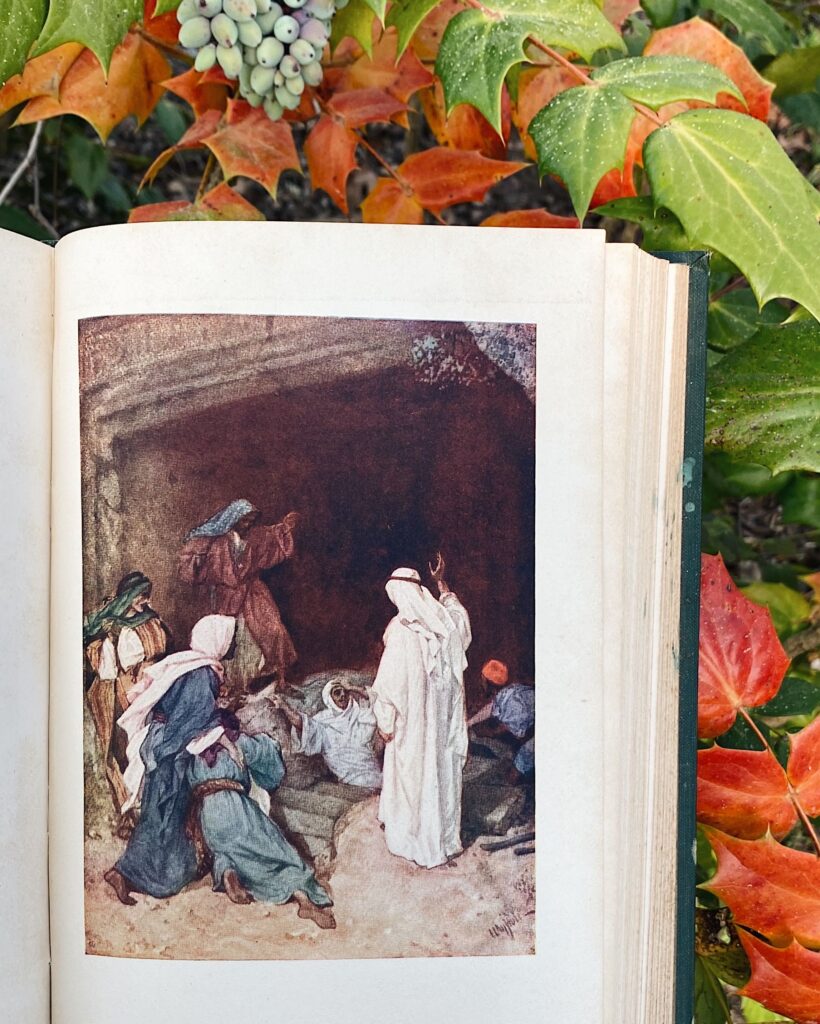

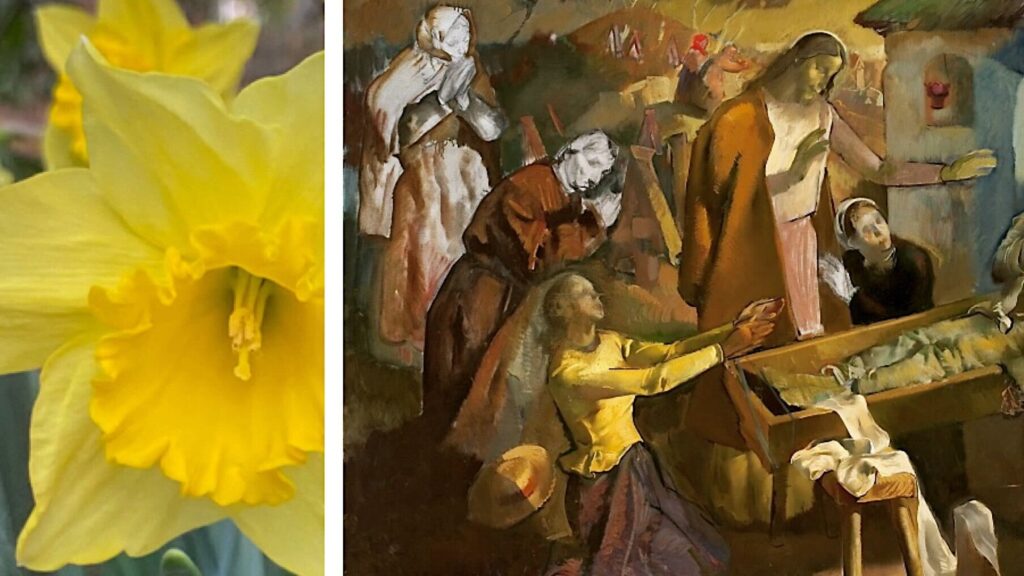

It is conceivable that the final answer may be that death is less momentous in the thought of God, who knows the hereafter, than to us, who are still in the dark. Christ wept, not for Lazarus: his sorrow was for the griefs that fall upon all men, as upon the two sisters. Perhaps He would have said, ‘If they only knew!’

The paragraph reflects some of Mason’s most profound thoughts about life and death. In today’s poem she takes up the theme in verse. “What then is ‘death’?” a timid soul asks our Lord. His answer expresses Mason’s understanding of His teaching, an understanding that is life to the soul. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVII

“All four gospels tell us that Jesus’ hearers accused him of being either possessed by, or in league with, the devil,” observes N. T. Wright. In the Gospel of John, we find the accusation in chapter 8.

Wright reflects, “Clearly, this isn’t something the early church would have made up; equally clearly, then, Jesus must have been saying and doing things that were remarkable enough, and disturbing enough, to make people throw such an accusation at him. What precisely was he saying here, and why, in the end, did they try to stone him to death?”

Charlotte Mason’s imaginative poem points the way to an answer. Read or hear her dramatization of the accusation of John 8:52, and of our Lord’s reply. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLVIII

“The real question,” writes F. Leroy Forlines, “is: Is fallen man a personal being, or is he sub-personal? … Does God deal with fallen man as a person? If He does, He deals with him as one who thinks, feels, and acts. To do otherwise undercuts the personhood of man. God will not do this—not because something is being imposed on God to which He must submit, but because God designed the relationship to be a relationship between personal beings. Human beings are personal beings by God’s design and were made for a personal relationship with a personal God. God will not violate His own plan.”

Jesus Christ, the very form of God, came to His own, and His own did not receive Him. He pleaded, He reasoned, He warned, He persisted, He pursued. But He would not force. He would not violate His own plan. Read or hear about the unlimited solicitude of Christ for His own in Charlotte Mason’s poem.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem XLIX

“Moses wants to know, to have certitude,” writes Walter Brueggemann, describing one of the most mystical and mysterious passages of the Old Testament. “Moses wants to know about the future and the mode of God’s presence with Israel.”

Moses pleads and God responds. “My Presence will go with you, and I will give you rest,” He assures him. Moses makes a second request. God responds again, “I will also do this thing that you have spoken.”

“Yahweh … seems to give over to Moses all that has been asked,” explains Brueggemann. “Moses, one more time, is relentless. He has now received assurance of ‘face,’ ‘rest,’ and ‘favor.’ Now he asks one more request: ‘Show me your glory.’ ‘Glory’ bespeaks God’s awesome, shrouded, magisterial presence, something like an overpowering light. It is in this passage as though the request for glory is to draw even closer, more dangerously, more intimately, to the very core of God’s own self.”

Amazingly, God grants this final request too. What does Moses see? That is the contemplation of today’s poem by Charlotte Mason. I listened to it and chills ascended my spine. It is a devotion that must be heard to be believed. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem L

“When I ask the high school students at my church to name a celebrity,” writes Rebecca DeYoung, “they can instantly rattle off a list of twenty. When I ask them to say who their heroes are, their response is usually quiet silence with furrowed brows.”

DeYoung writes these words in the chapter on vainglory in her valuable book Glittering Vices. She continues:

After they think about it awhile, however, a few name their grandparents as the people they most admire. Their heroes are people whose names aren’t even known in the next town, much less nationwide. When we compare what the celebrities are well known for and what our heroes are admired for, we find a chasm between people whose glory far outstrips the value of the goods for which they receive it, and people whose worth far outstrips any glory they will ever receive.

And yet “we don’t have to be famous … to embrace the goal of being well known and well liked, publicly approved of and applauded.” Deep down inside we want to be celebrities, not heroes. Our glory we must show.

This craving to display our own glory is the subject of today’s poem by Charlotte Mason, and she contrasts this vainglory to the glory of our Lord. Read or listen here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LI

“For it is not Humility to think ill of ourselves;” writes Charlotte Mason in Ourselves; “that is faint-hearted when it is not false. Humility is perhaps one with Simplicity, and does not allow us to think of ourselves at all, ill or well. That is why a child is humble.”

If that is humility, then what is glory? According to Charlotte Mason’s poem, it too is perhaps one with Simplicity. “He who wears [glory] knows not he’s adorned of God,” she writes, “who alone gives honour.”

Since Christ was humble, He did not glorify Himself. But God, who alone gives honor, glorified His Son. So Charlotte Mason poetically paraphrases Christ’s words:

“Ere God had laid

The foundations of the world, lo, I was there

In council with the Father. No prophet spake

But as I gave him words: no patriarch

Walked humbly with his God and gave their meat

To children and children’s children, but I was there

Sustaining that good man in righteous ways.”

It’s blasphemy or it’s truth. Read or hear Charlotte Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LII

In John 8:58, Jesus Christ says, “Most assuredly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I AM.” Fr. Lawrence R. Farley explains the meaning of these words:

The Greek for Jesus’ claim “I am” is ego eimi. In other contexts, the words ego eimi could mean no more than “I am the one”… In this context, however, it clearly means more, since Christ’s hearers responded by trying to stone Him for alleged blasphemy.

It is, in fact, a reference to the Divine Name of God, which He revealed to Moses at the burning bush in Exodus 3. At that time, Yahweh was asked by Moses what His Name was, and He responded, “I am that I am”—in the Greek Septuagint, ego eimi…

By declaring to the Jews “I am,” Christ was claiming nothing less than that He was the One who revealed Himself to Moses at the burning bush, that He was one with the Father, the eternal I Am.

Fr. Farley helps us see that Christ was speaking to Moses at the burning bush. Charlotte Mason’s poem on this verse imagines so much more: Christ speaking to Enoch, Methuselah, and David.

But Mason imagines even more than that. Christ appearing to conquerors and philosophers, even the most famous philosopher of all time. Read or listen to Mason’s wondrous poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

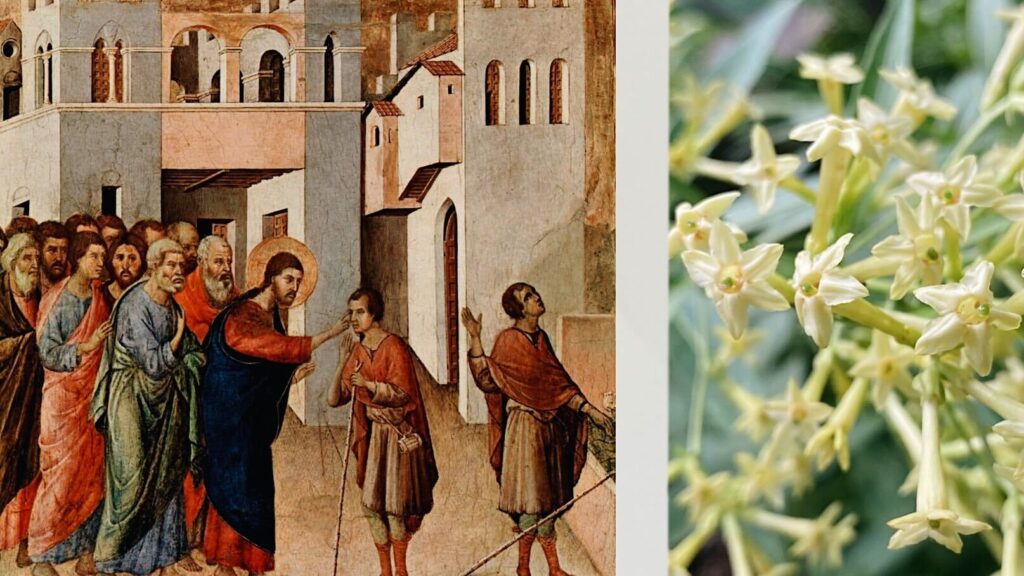

Book IV Poem LIII

In Carol A. Newsom’s deeply moving commentary on the Book of Job, she gives special attention to the words of Elihu. Elihu “is a formidable thinker—and a dangerous one… [He] articulates a powerful idea: God intentionally sends suffering to people in order to make them better—indeed, to save them.” Newsom explains the enduring appeal of this idea:

Like the notion of suffering as punishment for sin, it organizes the disorienting chaos of suffering into a meaningful pattern. Fearing meaninglessness almost above all else, people are willing to pay a great deal to restore a meaningful structure to experiences over which they have no control.

In the tenth chapter of the Gospel of John, the disciples meet a man who had no control over his plight: he was born blind. “Fearing meaninglessness almost above all else,” the disciples wanted answers. Surely Jesus would know. Was this blindness a punishment for sin? Whose sin?

Our Lord does not answer them the way they expected. Charlotte Mason’s poetic reflection on His words points us to a different perspective on the suffering over which we have no control. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LIV

Mystery surrounds the origin of narration in the Charlotte Mason method. Of course narration is introduced in Home Education on pages 231–233. Since this was Mason’s first volume, it may be supposed that narration was there from the start. But these pages were new to the Fourth Edition published in 1905. The earlier editions were silent on the topic. They did not even mention the word.

Narration first appeared in the PNEU literature in the very first programme, dated 1892. In June of that year, Mason’s Parents’ Review article “The Home School” revealed the first description of the practice that became a hallmark of her method: “Now the Parents’ Review School requires a good deal of Bible study. The suggestion as to method is, ‘Read aloud to the children a few verses, deliberately, carefully, and with just expression; require them to narrate what they have listened.’”

The first narration was the narration of Scripture.

Professors Chalcarft, Elton–Chalcarft, Ackroyd, and Jones recently published a monograph exploring Charlotte Mason’s volumes of sacred poetry. These researchers shed further light on the mystery as they write: “The method of reading or listening to a reading, followed by recall/narration, was itself an importation into all forms of reading, of a method first grounded in learning the Bible. [Mason’s] biblical hermeneutics, so to speak, became the bedrock of her educational philosophy and emphasis on reading and recall/narration.”

“Now this is no parrot-exercise,” clarified Mason in her final volume. “It is only by trying the method oneself on such an incident, for example, as the visit of Nicodemus or the talk with the woman of Samaria” that one can see the life and power of narration.

Imagine when Mason narrates the story of a man born blind who begins to see. It opens the eyes of the heart to new light. Listen or read it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LV

“The function of reason,” explains Charlotte Mason in her Short Synopsis, “is to give logical demonstration (a) of mathematical truth, (b) of an initial idea, accepted by the will.” Once the will has accepted an idea, reason rushes in to approve. And so fallacy after fallacy is committed with “the acquittal of that spurious moral sense which supports with its approval all reasonable action” (vol 2, p. 54).

As with several of Mason’s principles, the building blocks of this principle may be found in William Carpenter’s Principles of Moral Physiology. He notes the uncanny ability of reason to advocate for any position, however untrue: “We speak even now of an ‘ingenious argument,’ when we have in view rather the skill with which it is conducted, than the truth it is to support; in fact, our admiration is sometimes most called forth by the Ingenuity which is exerted to sustain a position we regard as untenable” (p. 504).

The Pharisees were confronted by an incontestable miracle: a man born blind could see. “Now we know that God does not hear sinners,” said the healed man. “Since the world began it has been unheard of that anyone opened the eyes of one who was born blind. If this Man were not from God, He could do nothing” (John 9:31–33).

But the Pharisees, like us all, possessed the power of reason, ready to come to their aid. They contrived an argument that was “ingenious.” They exerted their power to sustain a position that was manifestly untenable.

Charlotte Mason’s poem brings the scene to life, with constructed dialog, read with feeling and power by @antonella.f.greco. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

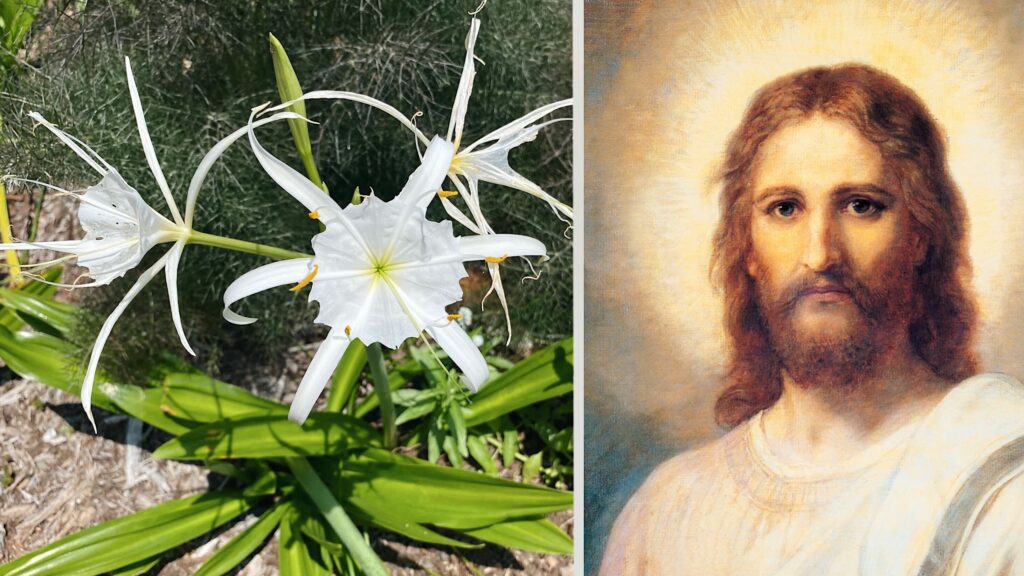

Book IV Poem LVI

The slim 2023 volume entitled Reading Charlotte Mason’s “The Saviour of the World” in Past and Present Contexts by David Chalcraft et al. contains a fascinating analysis of the six poetry volumes across multiple dimensions and perspectives. But amidst this careful examination of the poems and their context, the authors make an apparently incidental remark about Mason herself. The remark seems ancillary to their thesis, and yet to me is the most profound sentence in the book. In fact, it perhaps the single most beautiful sentence I have ever read about Miss Mason:

Mason’s educational philosophy did not exist outside of her personal identity and her seemingly infinite love for Jesus Christ, her Saviour.

A seemingly infinite love for Jesus Christ. It does indeed radiate from almost every page of Mason’s poetry. And what is the source of this love?

In today’s poem Mason describes the experience of a man born blind who by Christ’s miracle was made to see:

“Lord, I believe!” he cried, who had thought to miss

The common sights of life, or bird, or tree,

When, lo, his eyes were opened, and to this—

The Vision of his Saviour!

What is the source of Mason’s love? It was the same source for the man in her poem. Mason’s eyes were opened too, and to this: a vision of the Saviour of the World. Read or hear the overflow of love here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book IV Poem LVII

In John 9:24, the Pharisees say to the man born blind, “Give God the glory! We know that this Man is a sinner.”

The man’s famous answer rings through the centuries: “Whether He is a sinner or not I do not know. One thing I know: that though I was blind, now I see.”

“The expression in every age has been regarded as a happy illustration of a true Christian’s experience of the work of grace in his heart,” writes J. C. Ryle. “There may be much about it that is mysterious and inexplicable to him, and of which he knows nothing. But the result of the Holy Ghost’s work he does know and feel. There is a change somewhere. He sees what he did not see before. He feels what he did not feel before. Of that he is quite certain. There is a common and true saying among true Christians of the lower orders: ‘You may silence me and beat me out of what I know: but you cannot beat me out of what I feel.’”

Charlotte Mason poem about the blind man’s expression is entitled simply “Evidence.” She joins the chorus of believers throughout the ages cry out, “We see!” Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LVIII

How do we keep our hearts faithful to the Lord, and encourage our children to do the same?

If we think believers are “silly sheep,” then perhaps our best bet is to “fence them in,” to keep our children (and ourselves) in a safe, enclosed space which we hope will keep the robber out.

But what if sheep can be sensitive instead of silly? What if they can learn to know the voice of the shepherd that is “music in their ear”? And what if they can learn to shun the voice of a stranger?

Today we begin a series of poems by Charlotte Mason on Jesus the Good Shepherd. Listen or read to the beautiful poem by Miss Mason about sheep who delight in the music of their Lord. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LIX

Years ago at university I was a young man on a large campus. It was easy to feel lost in the crowd, far from home and very much on my own. I used to like to retreat to lonely places to find refuge in prayer. It seemed there was no lonelier place on campus than the two or three chapels built for a different age than mine.

One in particular became special to me. After many months I told a friend about this chapel. “One of the stained glasses is of me,” I said. Incredulous, my friend wanted to see the place. The time came and I pointed to the stained glass window. There was Jesus, the Good Shepherd, holding a little lamb. I pointed to the lamb sand said to my friend, “See? There it is. It’s me.”

No less beautiful than that stained glass window is Charlotte Mason’s poetic portrait of the sweet shepherd. He leads us to “knowledge, poems, pictures, at his will.” And He holds us, no matter how lost or alone we may feel. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LX

“Feed us, the children, as sheep.”

This prayer we find in chapter 9 of Christ the Educator.

The writer continues, quoting Jesus: “‘I will be their shepherd,’ he says, ‘and I will be close to them,’ … ‘They shall call on me,’ he says, and I will answer, ‘Here I am.’”

And then the writer concludes: “Such is our Teacher, both good and just. He said he had not come to be served but to serve, … he who labored for our sake and promised ‘to give his life as ransom for many,’ a thing that, as he said, only the good Shepherd will do.”

And so Christ the Educator is Christ the Shepherd who lays down His life for the sheep.

The writer was Clement of Alexandria, writing around the turn of the third century. It was about that same time that the first Christian art began to emerge. In the Catacombs of Priscilla, an unknown artist drew the Good Shepherd on the ceiling, a symbol in art echoing Clement’s symbol in words.

Charlotte Mason offered her own symbol too, a symbol in poetry. It too calls us to revere the beautiful Shepherd, the One who stood with us when the hireling fled. Read or listen here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXI

“It is not a light thing to claim to be God,” wrote Watchman Nee in 1936. “A person who makes such a claim falls into one of three categories. He must belong to one of these three categories; he cannot belong to all three. First, if he claims to be God and yet in fact is not, he has to be a madman or a lunatic. Second, if he is neither God nor a lunatic, he has to be a liar, deceiving others by his lie. Third, if he is neither of these, he must be God.”

Many of those who heard Christ speak on earth chose the first option. “He is mad,” they said. This false shepherd, they said, was demonic.

Charlotte Mason’s poem on Christ the Shepherd dramatizes the words of these men. We feel the force of their objection. But in her poem we also read a response.

“There is no need for us to prove if Jesus of Nazareth is God or not,” wrote Watchman Nee. “All we have to do is find out if He is a lunatic or a liar. If He is neither, He must be the Son of God. These are our three choices. There is no fourth.”

Read or hear Mason’s poem here which brings the third option to light.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXII

The penultimate chapter of Charlotte Mason’s Ourselves Book I sets before the reader an ominous image. It is of “four cross-roads where the companions divide.” All four are broad roads with many travelers, and each bears a sign that says “no harm.” All of us are tempted at one time or another by every one of the four ways. We are allured. We are enticed. And when we begin to slide, “our only chance,” writes Miss Mason, “is to struggle back by the uphill track of duty.”

She points to human effort. Grasp the inspiring idea. Make the choice of will. Form the good habit. Embrace the duty. Resist the “cross-roads of vice.” You can do it!

It’s all good advice; it’s all wise, helpful, and true. But it’s only half the story. In Charlotte Mason’s poetry she reveals the other side of the scene. We are like sheep and those cross-roads are appealing. The pastures seem so green. Duty, habit, and will are failing. We have started to slip away.

Our only hope is for a shepherd, and according to Miss Mason, our shepherd comes seeking. Read or listen to her poem “The vagrant sheep,” and when you read Ourselves, remember that all of the wisdom and advice it contains assumes the loving presence of an Unseen Hand. Find the poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXIII

In his Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus refers to the Feast of Tabernacles as “the holiest and greatest feast.” It took place in late September or early October and “was a time of thanksgiving for harvest. It was a happy time; devout Jews lived outdoors in booths made of tree branches for seven days as a reminder of God’s provision in the desert during their forefather’s wanderings.”

About two months later, the Jewish people celebrated the Feast of Dedication, which is today known as Hanukkah or the Feast of Lights. It was celebrated for eight days in December to commemorate the reconsecration of the temple by Judas Maccabeus in 165 BC.

Gail R. O’day observes that John 7:1–10:21 records events and interactions that took place at or around the Feast of Tabernacles. Then verse 22 transitions to the Feast of Dedication. “Jesus is still in Jerusalem,” she writes, “but the time of year has changed. Tabernacles was celebrated in late September/early October, the Feast of Dedication in December.”

In C. C. James’s The Gospel History, the chronological basis for the six poetry volumes of Charlotte Mason, the entire record of both festivals (John 7:1–11:54) takes place between events recorded in the Synoptic Gospels (between Luke 9:50 and 9:51). Charlotte Mason closely followed his chronology and also noticed the gap in the Gospel of John between the two feasts.

Commentator Gail O’day asks, “How is the chronological gap between the two halves of John 10 to be understood?” For her and many others the question is to be answered theologically. But for Miss Mason, the question is to be answered by the sanctified imagination. Where did Jesus and His disciples go “Between the Festivals”? What did he teach them? What did He say?

Follow this link to read the poetic answer by the woman and teacher who spent her life meditating on the Word of God.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXIV

What happened between two feasts? The Bible is silent on those two months or so between the Feast of Tabernacles and the Feast of Dedication. The Bible is silent, but Charlotte Mason’s imagination is not. If Christ were alone with His disciplines during that time, what would He undertake to do? What would He teach? For Mason, there is little doubt, as she sought “a whole conception of Christ’s life among men.” Read or hear Mason’s poem “The months of teaching” here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXV

In 165 BC, Judas Maccabaeus said to the men of his army, “Behold, our enemies are crushed; let us go up to cleanse the sanctuary and dedicate it.” For three years the temple of Jerusalem had been shrouded in darkness and desolation. Judas Maccabaeus came to bring light.

They rebuilt the altar, they rebuilt the sanctuary, and they consecrated the courts. “Then they burned incense on the altar and lighted the lamps on the lampstand, and these gave light in the temple. They placed the bread on the table and hung up the curtains. Thus they finished all the work they had undertaken.”

Finally after a great celebration, “Judas and his brothers and all the assembly of Israel determined that every year at that season the days of the dedication of the altar should be observed with gladness and joy for eight days,” and so the Feast of Dedication was born.

Nearly two centuries later, after spending two months in the wilderness, Jesus Christ returned to Jerusalem. He came to the temple once again to bring His light. It was the Feast of Dedication. What was the reaction of the people when Jesus “was walking in the temple in Solomon’s porch”? Charlotte Mason captures the moment in her poem, which you can read or hear here.

@artmiddlekauff

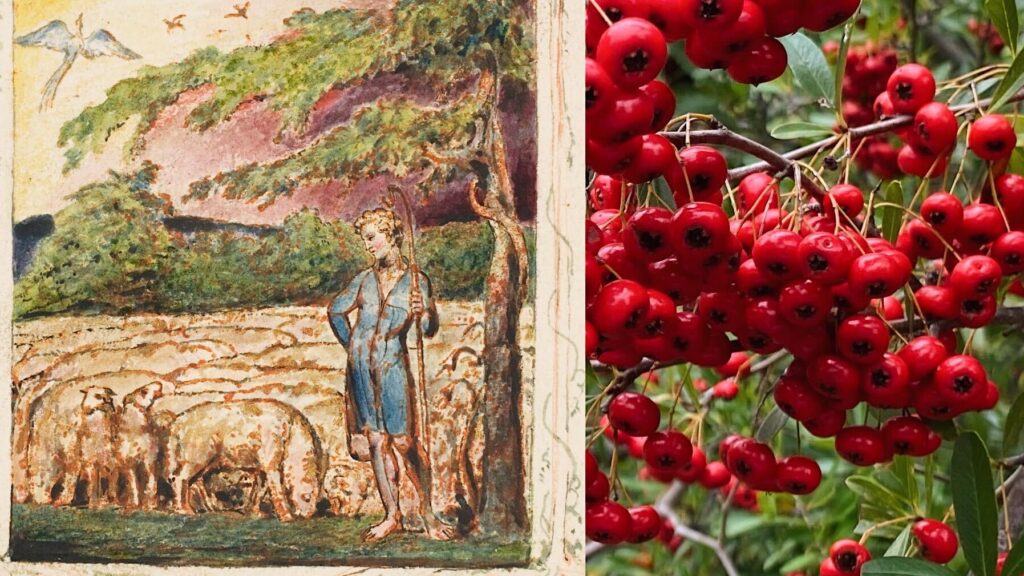

Book V Poem LXVI

When William Blake published his famous poem “The Shepherd” in 1789, it was illustrated with a painting by his own hand. He wrote of “the Shepherd’s sweet lot”:

For he hears the lambs’ innocent call,

And he hears the ewes’ tender reply;

He is watchful while they are in peace,

For they know when their Shepherd is nigh.

Blake capitalized the word Shepherd, pointing to Jesus the Good Shepherd. The lambs know when their Shepherd is nigh, which even more specifically evokes John 10:27: “My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me.”

The passage in John recounts Christ’s continued controversy with the religious leaders. “You you do not believe,” said Jesus, “because you are not of My sheep.” In Charlotte Mason’s sixth poem on the Good Shepherd, she explores the lambs who know when their Shepherd is nigh, and the men who refuse to be regarded as sheep. Read or hear her thoughtful poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXVII

Only once in the Gospel of John is Jesus formally accused of blasphemy. According to Leviticus 24, the penalty for blaspheming is to be stoned to death. When Christ’s auditors begin to pick up stones, Jesus responds by saying, “Is it not written in your law, ‘I said, “You are gods” ’? If He called them gods, to whom the word of God came (and the Scripture cannot be broken), do you say of Him whom the Father sanctified and sent into the world, ‘You are blaspheming,’ because I said, ‘I am the Son of God’?”

It is what Gail O’day describes as “an intricate argument from Scripture”:

Jesus’ argument … employs several exegetical techniques common to first- and second-century Jewish exegesis. Jesus’ exegesis may seem strained to contemporary exegetes, but it falls solidly within the range of exegetical approaches of first-century Judaism…

First, Jesus cites only the first half of Ps 82:6, even though he clearly presupposes the rest of the verse … in his argument (see v. 36).

Second, in rabbinic argumentation, a comparison could be made between two biblical texts simply on the presence of the same word in both texts, even if the words occur in distinct contexts and with quite different meanings. Jesus employs this technique when he compares ‘gods’ to God (vv. 35–36).

Third, his main line of argumentation follows the common rabbinic pattern of arguing from the lesser to the greater. That is, if Scripture speaks of human beings who receive the Word of God as gods, how can it be blasphemy for Jesus to speak of himself as God’s Son?

For the Gospel reader, there may be an additional level of meaning in this argument from the lesser to the greater, because Jesus not only receives the Word of God like those of whom Ps 82:6 speaks, but he is the Word of God (1:1, 14).

These words of Christ were a source of special fascination to Charlotte Mason. In today’s poem, she explores the dialog with the religious authorities. Next week, we will hear her stunning poetic inference. Read or hear “They take up stones to stone Him” at this link.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXVIII

One spends but little time in Charlotte Mason circles before one sees images of a massive fresco on the wall and ceiling of the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Although the fresco’s title now is The Triumph of the Catholic Doctrine, among Charlotte Mason enthusiasts it is often referred to simply as “The Great Recognition.”

This informal title is taken from the name of Chapter 25 of Parents and Children: “The Great Recognition Required of Parents.” It is the idea that “God, the Holy Spirit, is Himself the supreme Educator of mankind.”

Across the range of her writings, Charlotte Mason pointed to many Scriptures in support of this idea, including 1 Samuel 10:10, 1 Chronicles 28:11-12, Isaiah 28:24-26, John 16:12, James 1:17, and James 3:17.

In her poetry volumes, however, she drew perhaps the most extraordinary connection between the Gospels and the Great Recognition. Writing in 1911, she said of John 10:14, “It seems to me that there exists no better comment upon the saying, ‘I said, ye are gods,’ than this expression of mediæval philosophy as embraced by the Church.” Read or hear the striking poem that boldly stands on one of the most mysterious verses of the New Testament. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXIX

“In the light of the rising attacks, Jesus went back across the Jordan, to the east side, away from Jerusalem and Judea, to the place where John had been baptising in the early days,” explains D. A. Carson, commenting on John 10:40. “The symbolism is palpable. John the Baptist had prepared the way for the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry, and now that public ministry is drawing to a close, while the Baptist’s ministry is reviewed once more.”

Jesus had said, “I sent you to reap that for which you have not labored; others have labored, and you have entered into their labors.” Charlotte Mason’s touching poem explores the symbolism of this moment, where the seed John sowed bore fruit for eternal life. Would the Baptist ever know? Read or hear Mason’s poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXX

“Ancient Bethany occupied an important place in the life of Jesus,” writes Larry McGraw. “Jesus often found Himself staying in Bethany at the home of his closest friends as He ministered in Jerusalem.”

“Located on the Mount of Olives’ eastern slope, Bethany sat ‘about two miles’ (John 11:18 HCSB) southeast of Jerusalem,” he continues. “Bethany became the final stop before Jerusalem just off the main east-west road coming from Jericho. Being at the foot of the mountain, the people could not see Jerusalem, thus giving Bethany a sense of seclusion and quietness.”

How inviting to stay in a place that is secluded and quiet. And even nicer to stay in the house of one’s closest friends. It is this vision of Bethany that Charlotte Mason evokes in her poem entitled “The house of a friend.” The poem is the first of a series of 14 extraordinary poems about one of the most extraordinary miracles of all time. Worrisome news will come to Christ from this village. But for now, read or listen as Mason paints her picture of “a place where we may go for company in loneliness.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXI

In Book II of Ourselves, Charlotte Mason narrates a passage from Sir Walter Scott’s novel Redgauntlet. Alan Fairford had worked hard to establish himself in his career. As a young attorney, he was having his first appearance in court and was making progress on a tough case. Then a piece of paper is handed to him. It’s a message from his close friend Darsie Latimer. His friend is in danger.

“He stopped short in his harangue—gazed on the paper with a look of surprise and horror—uttered an exclamation, and flinging down the brief which he had in his hand, hurried out of court without returning a single word of answer to the various questions, ‘What was the matter?’—‘Was he taken unwell?’—‘Should not a chair be called?’ etc., etc.”

Two sisters had a brother who was in danger. Like Darsie, they had a close friend. But their friend was special. Not only could He comfort, He could also cure. For He was the Son of God. And surely He would come quickly. Experience the moment in Charlotte Mason’s poem “The message sent.”

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXII

“Now Jesus loved Martha, and her sister, and Lazarus.” And that should be all we need to know. Jesus, the Son of God, all-loving and all-powerful. “And all were sure what He would do,” writes Charlotte Mason: He would say, “Let us make speed, Go we to cheer the sisters two!”

But that is not what He did. “He abode at that time two days in the place where he was.” Waiting. Staying. Abiding. Why not go to the ones He loved? As the year draws to a close and we enter a new season, let us reflect with Charlotte Mason on our loving, waiting Lord. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXIII

“In that Heart where every pain found its pity,” writes Charlotte Mason, “there was none for the three who tasted death—only for the grief that mourned them.”

One of the three Mason refers to, in this poignant passage from Formation of Character, is Lazarus.

In the poem “The Master delays,” Charlotte Mason envisions the moment Christ tells his disciples that Lazarus is asleep. “‘Sleep is good,’ say they, ‘none weeps for such reprieve.’” But Mason knew the Heart where every pain found its pity. She understood this Heart would weep. Read or hear the poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXIV

In the middle of the Gospel account of the raising of Lazarus, we are introduced “to one of John’s great minor characters.” N. T. Wright explains:

Thomas is loyal, dogged, slow to understand things, but determined to go on putting one foot in front of another at Jesus’ command. Now he speaks words heavy with foreboding for what’s to come: ‘Let’s go too, and die with him.’ They don’t die with him, of course, or not yet, but this is certainly the right response. There is a great deal that we don’t understand, and our hopes and plans often get thwarted. But if we go with Jesus, even if it’s into the jaws of death, we will be walking in the light, whereas if we press ahead arrogantly with our own plans and ambitions we are bound to trip up.

The title of today’s poem by Charlotte Mason is taken from the words of John’s great minor character. Read or hear it here, and consider what it really means to walk in the light.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXV

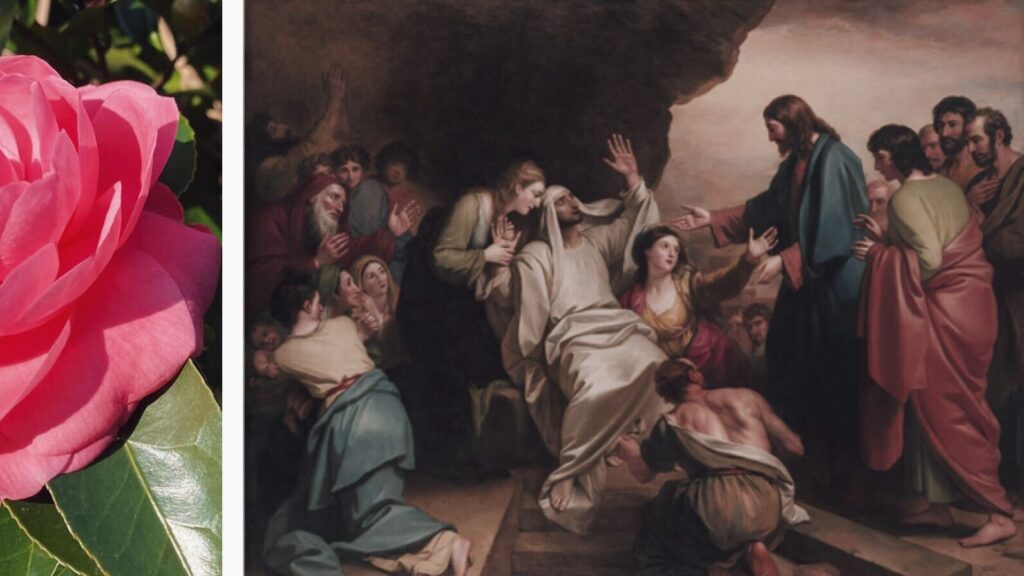

Samuel M. Ngewa describes what happened when Jesus finally reached Bethany:

On his arrival, Jesus was met by Martha, whose first words were, Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. These were exactly the same words spoken by Mary later. The statement probably echoes words the sisters had said to each other again and again, first as they waited for Jesus to come and then as they mourned their brother’s death.

Martha’s faith had not been shaken, for she also said, I know that even now God will give you whatever you ask. The ‘whatever’ in her statement does not seem to have included the resurrection of Lazarus. She was likely thinking in terms of everyday life, not of a movement from death to life.

Late one night over the Christmas holidays a few of us were still up chatting in the living room. My daughter asked a provocative question: “Do you ever pray for something that only God could do?”

I’ve thought about that question a lot in the weeks since. I pray for a lot of things, but these are all things that are possible, even likely. But do I pray for things that are impossible? It seems that Martha wasn’t ready to do so. Am I?

Join Charlotte Mason’s contemplation of faith as she reflects on Martha’s words. Find her poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXVI

Martha bore a grief deeper than anyone could know. Jesus offered her these words: “Your brother will rise again.” It’s not what Martha wanted to hear. She didn’t want some solution for some far off day. She wanted a solution for her grief right now.

N.T. Wright explains what happened next:

[Martha] isn’t prepared for Jesus’ response. The future has burst into the present. The new creation, and with it the resurrection, has come forward from the end of time into the middle of time. Jesus has not just come, as we sometimes say or sing, ‘from heaven to earth’; it is equally true to say that he has come from God’s future into the present, into the mess and muddle of the world we know. ‘I am the resurrection and the life,’ he says. ‘Resurrection’ isn’t just a doctrine. It isn’t just a future fact. It’s a person, and here he is standing in front of Martha, teasing her to make the huge jump of trust and hope.

Resurrection is a person. And He’s here right now. Read Charlotte Mason’s reflections on one of the most memorable phrases Jesus ever spoke. Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXVII

“Martha is the active, busy one,” explains N. T. Wright. “Martha had to hurry off to meet Jesus and confront him directly. Many of us are like that; we can’t wait, we must tell Jesus what we think of him and his strange ways. If you’re like that, and if you have an ‘if only’ in your heart or mind right now, put yourself in Martha’s shoes. Run off to meet Jesus. Tell him the problem. Ask him why he didn’t come sooner, why he allowed that awful thing to happen.

“And then be prepared for a surprising response. I can’t predict what the response will be, for the very good reason that it is always, always a surprise. But I do know the shape that it will take. Jesus will meet your problem with some new part of God’s future that can and will burst into your present time, into the mess and grief, with good news, with hope, with new possibilities.”

“Believest thou this?” asks Charlotte Mason in today’s poem. Read or listen, and then bring your cares to Christ. Find the poem here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXVIII

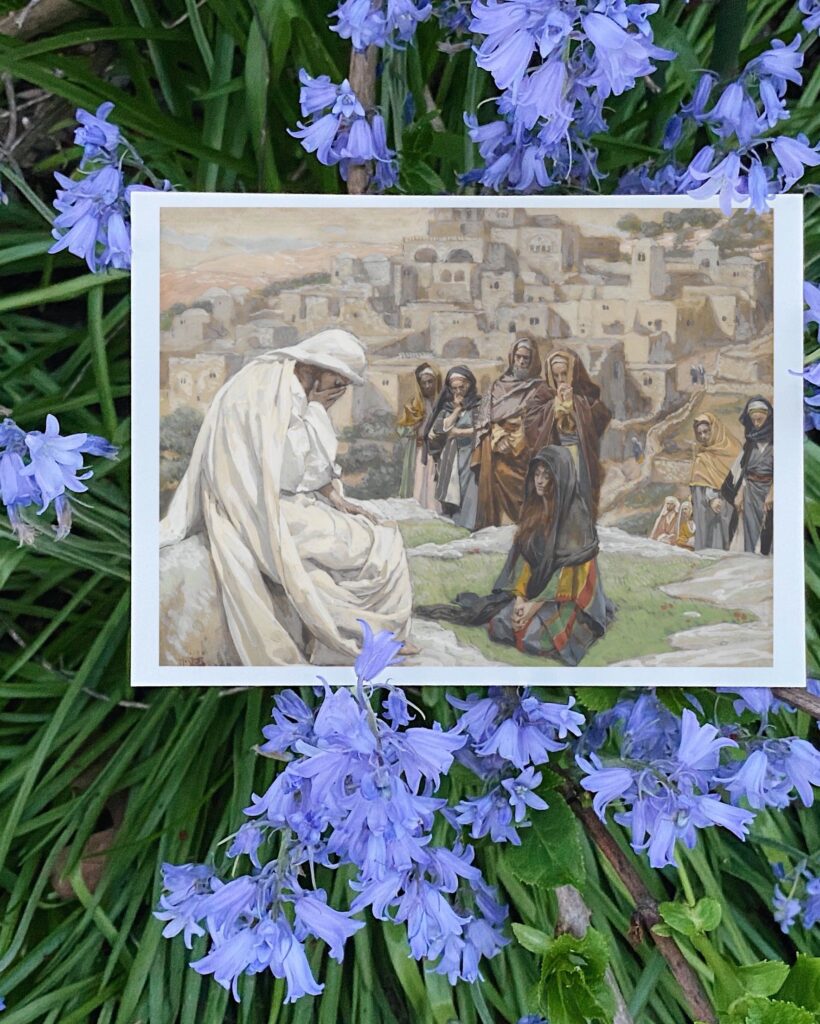

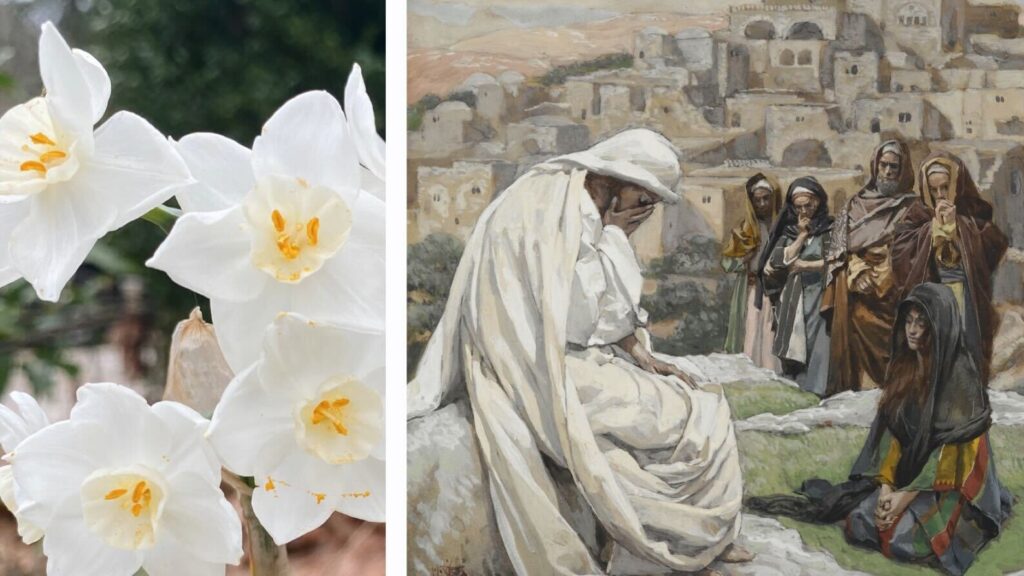

American artist Makoto Fujimura wrote in 2012, “‘Jesus Wept’ is, to me, the most profound passage in the Bible.”

“Jesus’ tears,” he reflected, “make no logical sense, as he came to Bethany with the specific mission to raise Lazarus from the grave. He told the disciples his mission (and why he intentionally delayed his arrival, knowing that Lazarus lay dying) and revealed to Martha that he was and is the ‘Resurrection and the Life.’ So why did he, upon seeing the tears of Mary, waste his time weeping, when he could have shown his power as the Son of God by wiping away every tear, telling people like her, ‘Ye of little faith, believe in me!’?

Fujimura couldn’t help but notice that Thomas Jefferson had cut the verse from his own edition of the Bible: “Jefferson’s rationalism allowed only a distant deity that made sense in reference to objective ‘scientific’ calibrations, not ephemeral marks of compassion.” Fujimura explained.

But N. T. Wright points out that whatever logic or Jefferson might say about this verse, “there can be no doubt of its historical truth.” He observes: “Nobody in the early church, venerating Jesus and celebrating his own victory over death, would have invented such a thing.”

As an artist, Fujimura found a model for his work in this profound and historical verse. “Art, like the tears of Christ, may seem useless, ephemeral and ultimately wasteful. But even though they evaporate into our atmosphere, the extravagant tears of God dropped on the hardened, dry soils of Bethany, or onto the ashes of our Ground Zero conditions, are still present with us. Because tears are ephemeral, they can be enduring and even permanent, as with ‘Jesus wept.’ In the same way, perhaps our art can be so as well. What seems, at first, to be an irrational response to suffering may turn out, upon deep reflection, to be the most rational response of all.”

Charlotte Mason offered her own art in remembrance of Jesus’ tears. It is an emotional response, a rational response, a poetic response. Read or hear it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXIX

“Jewish burial did not involve embalming, as it did in Egypt,” explains Gail R. O’day. “The body [of Lazarus] was anointed with perfume and wrapped, but after four days the effect of the perfume would be rendered null by the odor of the body’s decomposition.”

Mary was weeping. Jesus was weeping. And then the crowd turned hostile. “It must be His fault,” they reasoned. If He could perform miracles of healing, couldn’t He have kept His much-beloved friend from dying?

What could Martha do? Her “assumptions about the reality and power of death govern her response to Jesus,” notes O’day. “Even her exemplary confession of faith at 11:27 could not prepare her for the fullness of Jesus’ identity and gifts.”

No one could have been prepared for what would happen next. Read or listen to Charlotte Mason’s poem about “He, who tender deals.” Find it here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXX

Some years ago I had the opportunity to hear a wonderful lecture by a leading expert on Jonathan Edwards. The speaker had authored several books on Edwards, so he certainly had much to say about the man. I recall at one point he even said that Edwards was the greatest theologian America ever produced.

After the lecture I approached him with a few questions. And I couldn’t resist asking, “If Edwards is the greatest American theologian, then who was the greatest theologian of all?”

The author and professor hesitated only for a moment and then said, “Thomas Aquinas.” I remember his answer whenever I think of that towering 13th-century intellect whose thinking and writing have shaped countless hearts and minds over the past 700 years.

Historican Nick Needham explained, however, that Aquinas “never finished his masterpiece of systematic theology, the Summa Theologiae, because towards the end of his life (in December 1273) he abandoned writing entirely. When asked why, he replied that everything he had written seemed like ‘a piece of straw’.”

How could the writings of this greatest theologian of all time be a likened to piece of straw? According to Needham, many believe that Aquinas had “a glorious spiritual experience … during holy communion which (he said) made his writings appear worthless in comparison with the experience.”

In today’s poem Charlotte Mason compares what we think we know about the Son of God as compared to the glorious truth. “I am the resurrection and the life,” says Christ. Do we really believe? Consider with Miss Mason here.

@artmiddlekauff

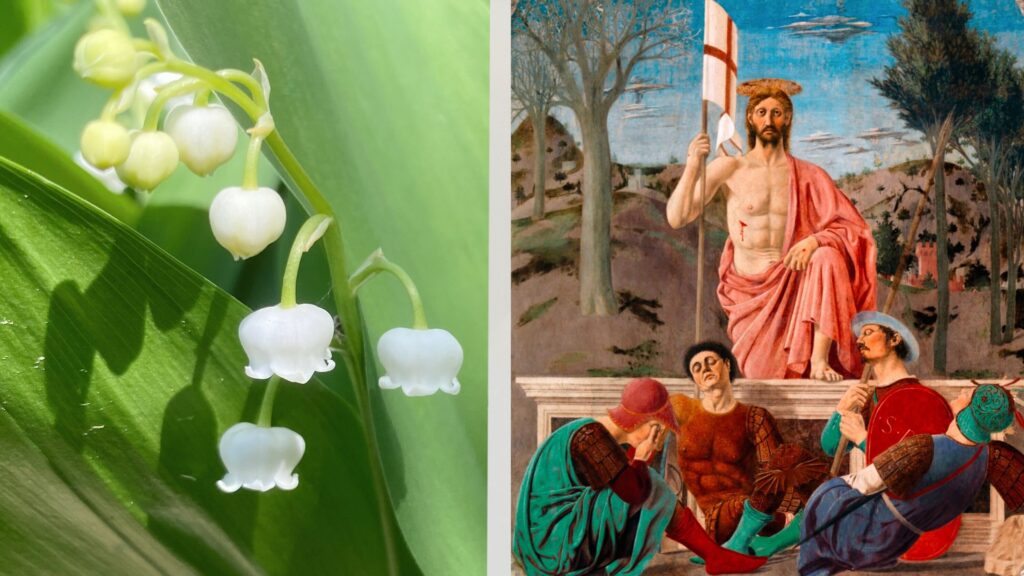

Book V Poem LXXXI

In the timeless devotional The Cloud of Witness, we see the calm logic of Edward Young (1683–1765) who appeals to the reader to believe in resurrection. Matter, he reasons, is never destroyed, so why should the immaterial not share this honor?

Further, if one still struggles to accept the notion of immortality, he asks, “Is it less strange that thou shouldst live at all?” And if by a miracle we live, then why not accept that “who gave beginning, can exclude an end”?

Charlotte Mason also believed in resurrection. And she believed in the miracle of life. Christ’s victory, she explains, is not just for the future. It is our life every day. Read or hear it in Mason’s inimitable words here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXXII

Henry Morris, the late Bible scholar and professor of civil engineering, wrote that “only God is able to perform miracles of creation.” He then examined the seven great signs of the Gospel of John from a scientific perspective. He considered how the simple molecular structure of water could be converted to the “far more complex molecular structure of freshly created wine.” He noted how the feeding of the five thousand transcended the law of the conservation of mass.

He hypothesized that Jesus created an “anti-gravitational force of unknown nature, enabling Him to walk on the surface of a stormy sea.” And Morris observed that “new bone, muscle, and other components” would need to be created for a man who had been unable to walk for 38 years to be instantaneously restored and able to support his own weight.

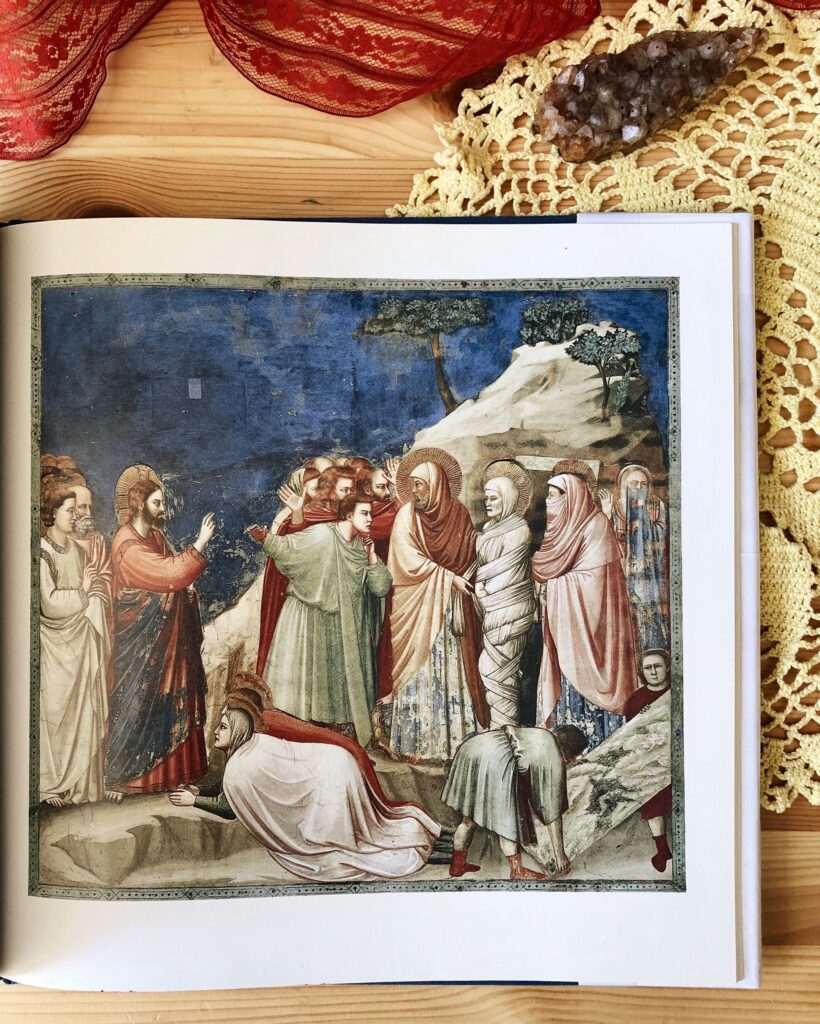

But at the end of the list, Morris cited the greatest sign of the seven. In the case of Lazarus, “not only were the limbs and eyes dead, but the whole body in this case, and for four whole days, so that putrefaction had set in. Nevertheless, at the creative word of Christ, all cells and functions were instantly restructured and reprogrammed, and even the departed spirit summoned again to the body, so that Lazarus lived.”

The words were so simple: “Lazarus, come forth!” But the work it accomplished was so profound. It is the title that Charlotte Mason chose for her poem about this great miracle of Christ. Mason, however, was not thinking about the restructured cells. She was thinking about the departed spirit. Read or listen here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXXIII

One of the great theological and devotional passages in Charlotte Mason’s writings appears in Book II of Ourselves. There she tackles the question that has baffled lay person and philosopher for centuries: the problem of evil. How do we reconcile a loving God with the suffering we see in the world?

Mason’s reflections on pages 89–90 of Ourselves are stunning. “Christ wept,” she writes, “not for Lazarus: his sorrow was for the griefs that fall upon all men, as upon the two sisters. Perhaps He would have said, ‘If they only knew!’”

Charlotte Mason’s final poem on the raising of Lazarus is the complement to this reflection in Ourselves. Entitled “The man who knew,” the poem considers the perspective of one who had spent four days on the other side of death. Her poem is more surprising and mysterious even than her reflections on the problem of evil in Book II of Ourselves. If only we knew, how would our life be different? Listen, read, and wonder here.

@artmiddlekauff

Book V Poem LXXXIV

“You will not surely die,” the Serpent said to Eve. “For God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

The temptation was irresistible. Man could be like God!